![]()

1

Home Again

When my mother died in April 1979 and my father eleven months later, I was prevented from performing my duty to comfort them when they took their last breaths. I had been stripped of my citizenship by the Burmese military junta after it toppled a democratic government in 1962. Failure to perform that final duty is a wound in me that will never heal.

I tried for many years to return to Burma, but it was in vain. Every time I applied for a visa I had to complete a long form giving the military regime detailed information about myself and my family. Then in 2001, after living for more than forty years as an exile in America, I was pleasantly surprised to be issued a visa. General Khin Nyunt, the second most powerful man in the junta, had authorized it. Khin Nyunt was chief of intelligence at the time and widely feared, but he fell from grace three years later.

The regime was using the Venerable Dr. Rewata Dhamma, a Burmese Buddhist abbot based in England, as an emissary to coax democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi and other opposition leaders into toning down their rhetoric. Early one morning in California, Dr. Rewata called me from Malaysia and said, “If I can get you a visa to Burma, will you go? I will speak to General Khin Nyunt.”

“I will, Reverend,” I told him. “But I don’t want them to trap me.”

“Don’t worry about that,” he assured me. He gave me the names and telephone numbers of two senior intelligence officers and told me to call them if I ran into a problem. I went into Burma with trepidation. I didn’t know what to expect, but I was emboldened by the holy man’s assurance.

During those forty years, I had been busy earning a living and raising a family in America. I had also been speaking out against the junta. When my wife, Riri, and I left Burma in 1961, I took a job teaching at the U.S. Army Language School (now the Defense Language Institute), at the Presidio of Monterey in California. I took out a mortgage in 1962, in order to provide a home for our first child, Zali. I became an American citizen in 1966, because being a stateless person was not an option.

The Junta, My Nemesis

When U Nu, the Burmese prime minister ousted in the 1962 coup, came to California in 1969, I secretly hosted him. Earlier in London, he announced his intention to raise an army to overthrow the military regime. He did not believe it was wrong by Buddhist tenet to kill the killers.

I launched, and for nineteen years published, a quarterly newsletter, The Burma Bulletin, as a chronicle of the movement and a voice for Burmese living abroad. I took every opportunity to expose the brutality of the military led by General Ne Win that had forcibly sealed the country off from the outside world. When widespread unhappiness erupted into unrest in August 1988, the military responded by killing thousands of protesters. The effect was like the lid coming off a pressure cooker. The massacre, the ensuing movement led by Aung San Suu Kyi, and her National League for Democracy’s overwhelming victory in the 1990 elections, which was nullified by the regime, had finally compelled the outside world to notice Burma. I had been a witness and a participant from afar in the country’s tortured history throughout my exile. But things had turned out differently than I had hoped.

I went to Burma in November 2001. I was apprehensive. Before I went, I made sure that family and friends were aware that I was going. One person I told was Betty Jane Southard Murphy, a Washington lawyer with connections to the senior Bush White House and a loyal friend for half a century. B. J. said, “If you run into a problem, let me know.” I also informed Denis Gray, the longtime Associated Press bureau chief in Bangkok, as well as Nick Williams Jr., the Los Angeles Times Bangkok bureau chief, and the Burma Desk at the Department of State in Washington. Members of my church’s prayer chain in Boulder, Colorado, lifted me up.

In the departure lounge at Bangkok airport were several Burmese, but only the women were dressed in native attire. They seemed cautious and reserved in their body language toward me; perhaps they suspected that I was associated with the military regime. By wearing Burmese national dress, which consisted of a collarless white shirt, a longyi or sarong, and a jacket called taik pon eingyi, I was making a statement of my cherished Burmese heritage. The longyi is of Indian origin, which the Indians call lungie. The taik pon eingyi [jacket] is of Chinese origin. Sandwiched between China and India, Burma draws from the cultures of both these giants.

I felt anxious and constricted, but I did not consider backing out. I vowed to myself that if I was interrogated I would tell the truth, but would not tell everything. I was not going to be intimidated.

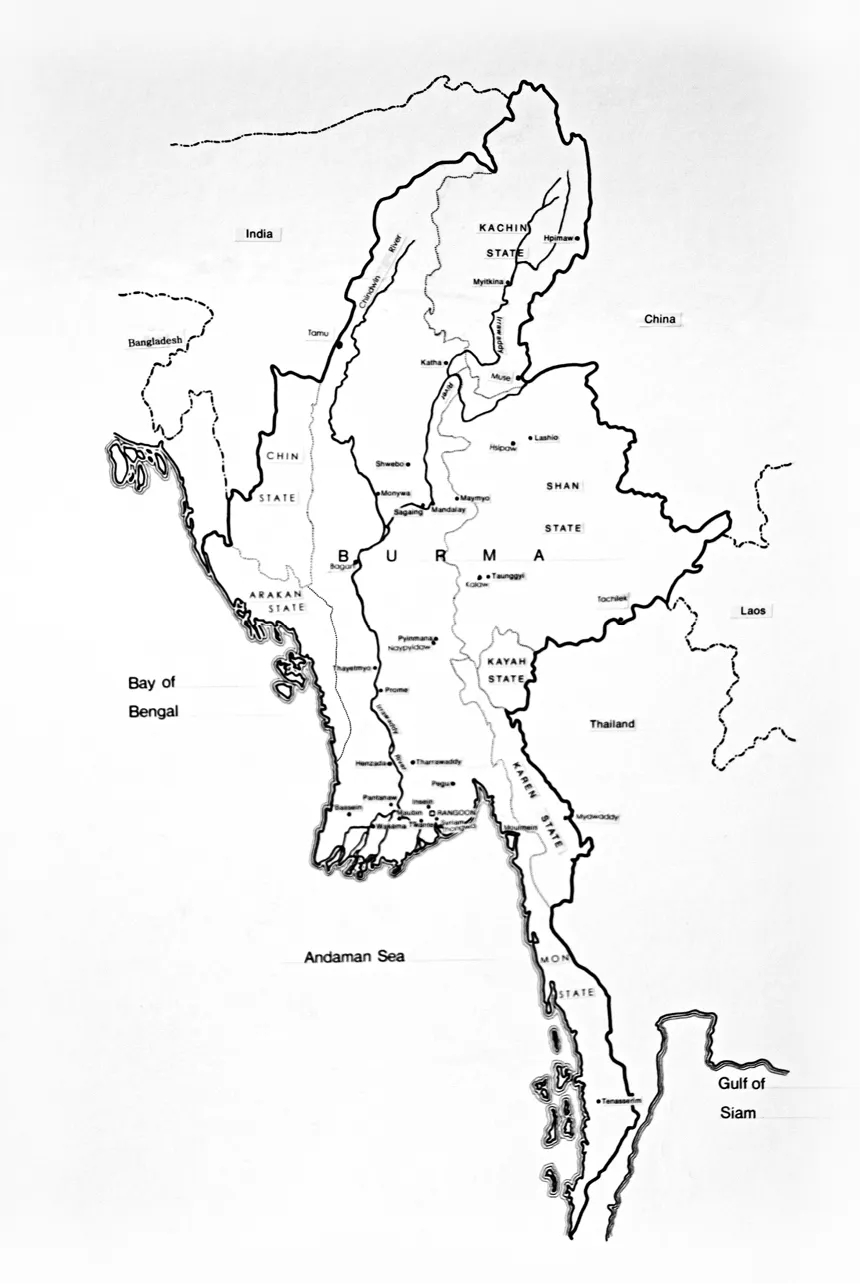

Map of Burma

As the plane came to a halt on the tarmac in Rangoon, I spied an armed soldier standing at the foot of the stairs. He was just guarding the plane, but my heart skipped a beat. In Burma we have a saying that if a ghost senses your fear he’ll frighten you all the more. (Superstitious Burmese believe in ghosts.) So I put up a brave front.

As the passengers disembarked, the lone Burmese monk on the plane nodded at me and asked, “Dagah gyi [benefactor]—what is your zah ti [origin, place of birth]?” “Thongwa ba, paya [Thongwa, Reverend],” I answered. The friendly exchange helped relax me.

In those days only a trickle of tourists went into Burma. I got into the immigration line for foreigners. There was a man, untidily dressed in a longyi, a short-sleeved shirt without a jacket, and flip-flops, scrutinizing the passengers. His eyes told me that he was military intelligence. When he spied me, the only person in the foreigners’ line dressed in Burmese attire, he said, “Myanmar passport holders are the next line.” I told him I didn’t hold a Burmese passport.

When the young women at immigration noted my age in the passport, they became deferential. “Oh, uncle,” the young ladies at customs greeted me. “Do you have any presents for us? We are poor.” I gave them a few lipsticks. As I was collecting my bags, I spotted two young women waving frantically at me from the other side of the glass partition. I was expecting somebody to meet me, but I didn’t know who would show up. When I got out of the secure area, I had to ask, “Whose daughters are you?” One turned out to be the daughter of a childhood friend and the other a relative. Neither had been born in 1961 when I left the country. Their fathers were long gone.

Outside the airport I saw soldiers standing guard in front of buildings. There were more cars. Forty years ago, privately owned automobiles had been few and far between; to get around, people had relied on public transportation and their own feet.

My plane arrived at 8:30 a.m. From the airport I made a beeline for Twante, my father’s birthplace and my boyhood hometown, about twenty-five miles away from Rangoon by ferry and road. My first duty was to do homage to my parents at their final resting place. Images of long years past flashed through my mind’s eye. Standing over their graves in the tiny church compound, I was emotionally exhausted.

Even though it was November, the heat and humidity were overwhelming. The Methodist school that my father had co-founded with an American missionary in 1919 still stood, but the football field was filled with dwellings. Private schools in Burma were nationalized in 1963, and the Methodist Mission had been broken up and occupied by squatters. The footpath behind the school had become a road, but the roads in Twante were little more than unpaved bullock cart tracks with bamboo-and-thatch houses lining both sides.

From my parents’ graves I went to Shan Zu, the town’s Shan quarter in the shadow of the Shwehsandaw Pagoda where a cousin’s family lived. From their home you could hear the pagoda’s tinkling bells. Twante had grown and was much more crowded than I had known it. In my day, you had to cross the Rangoon River on a sampan to Dalla and then take a bus to Twante, but the more practical route was by boat or sampan on the Twante canal. The road to the pagoda, which used to cut through bamboo groves and jungle, was now completely built up. Even though the town had grown, it had hardly developed. There was still no indoor plumbing, garbage collection, electricity, or telephones in most areas.

I ate lunch in Shan Zu, but I wanted to get back to Rangoon before dark. My family home in Twante was no more. I returned to Dalla and re-crossed the river on a filthy, ragtag ferry. I looked for life jackets on the crowded ferry. They were secured tightly in a difficult-to-reach place. I checked in at Yuzana Garden hotel, which in colonial times was the chummery [bachelor quarters] of Steel Brothers Company, a British mercantile conglomerate that was the setting of a Maurice Collis book, Trials in Burma (1938). A reception clerk later remarked that my voice sounded familiar. I kept mum. I did not want to let the cat out of the bag that she had indeed heard me on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Burmese Service in some interviews I had given and two pieces I had recently done on Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers and another on the American form of democracy. BBC shared several letters commenting on my contributions it had received from listeners.

The next day I called the U.S. embassy and asked to speak with Priscilla Clapp, the chargé d’affaires. The United States had withdrawn its ambassador from Burma after the 1988 uprising and conducted diplomatic relations with the junta at the chargé level, in rebuke. She was unavailable, but Karl Wycoff, the deputy chief of mission, was. I told him who I was and that I would like to see him. Apparently, the State Department had cabled the embassy to inform them of my coming. “I’ll come to your hotel,” Wycoff said.

When he arrived, I asked him whether I would be under surveillance. “Probably,” he said. “They use about fifty people to tail a person they want to keep under surveillance. You won’t see the same face twice.” He said he hailed a cab from the street to come to my hotel instead of using an embassy car. He wanted to avoid being tailed. He spent about forty-five minutes briefing me on the situation in Burma. I wanted the embassy to know my travel plans up country. He gave me his home and direct office phone numbers, and the 24/7 number for the embassy’s Marine guard station. I saw him one more time before I left the country. “If you run into a problem at the airport at departure, call,” he said. “Someone from the embassy will be there within fifteen minutes.”

An amusing incident took place while I was leisurely strolling westward on Merchant Street from Sulé (SOO-laye) Pagoda Road. A neatly dressed chap standing under a tree on the sidewalk made eye contact. A hand-scribbled sign ...