![]()

1

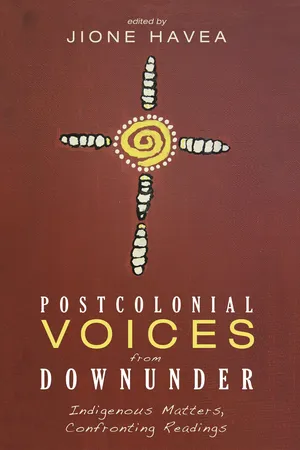

Postcolonize Now

Jione Havea

Now is the time to postcolonize. The invitation is serious. Lands, lives, liabilities, limits, longings, lore, and a whole lot more, remain unaccounted, unrecognized, uncompensated, unremitted. The invitation is also urgent—Postcolonize now. The invitation requires revisiting and rethinking the dreams and practices in and of Postcolonial Criticisms and Postcolonial Theologies. Accordingly, i set in this opening chapter a place at which the invitation to postcolonize could be embraced. Moreover, i will situate around that place the voices from downunder that speak within and through the covers of this book.

I will highlight and reflect on relevant issues in the rise of postcolonial criticism within Commonwealth and Third World Literature Studies, and its entry into biblical and theological studies where it cross-fertilizes with modes of contextual and liberation engagements. In the process i will address matters that, in my humble opinion, require the attention and involvement of biblical critics and theologians in the Asia-Pasifika (and beyond) who decide to wade into the currents of postcolonial criticism. These matters, spread out like reefs in the sea, include native color and agency (identity); foreign and local empires (power); oral and visual native texts (scriptures); and the overlaying nodes of the secular and the sacred (space). I will also situate the contributing voices to this collection of essays upon those proverbial reefs. The upshot of this multi-plying process is that the postcolonial voices from downunder presented in this monograph will at once be harboured as well as exposed.

Postcolonize this/thus

The stories of postcolonial biblical criticism have been told many times, and i will not repeat or interweave those here. I wish instead to highlight some of the elements that are pertinent for, and welcoming toward, the postcolonial voices from downunder that this monograph contains (ambiguity is intentional).

First, i draw attention to the rise of postcolonial criticism in the first world, within the halls of Commonwealth and Third World Literature Studies. From under the shadows of the British Empire and its former colony the United States of America, postcolonial criticism reaches out toward the so-called third world. Similar to the missionary and colonial projects that spread throughout the Asia-Pasifika (see the discussion of Emmanuel Garibay’s “The Arrival” below), postcolonial criticism is a Commonwealth project aimed to aid (save?) the third world. Or is this another exercise in colonial control?

The major theorists behind postcolonial criticism, at least the ones whose views have been privileged by the opportunities of publication and citation (e.g., Edward W. Said, Gayatri C. Spivak, Homi K. Bhabha), trace their roots back to the former British colonies of India and Palestine (in the regions of Asia and the Middle East, part of the so-called, and problematized, Orient) and they have admirers, followers and disciples in other regions, from Africa to Europe, to America and the Caribbean, to Pasifika and in between. They have critics as well in those same locations who ask: For which and whose third world do postcolonial theorists speak and advocate? From under the protection and comforts of British and American empires, do postcolonial theorists see the real struggles of the everyday third world(ed)? These questions would have been severe if postcolonial criticism was uni-form, rigid and static. This is not to push the questions under the mat, so to speak, but to register, engage and postcolonize them—the questions and the questioners deserve the attention of postcolonial critics who operate from colonial contexts.

Second, i note the entry of postcolonial criticism into the halls of biblical and theological studies. The aggravation of postcolonial biblical criticism and of postcolonial theologies is also in response to what happened, and continues to happen, in the third world, and this is clearly conveyed in the subtitle of the Voices from the Margin collection of essays: Interpreting the Bible in the Third World. One of the feats of this collection is its ability to fuse the horizons of biblical criticism with those of theological reflection, a move that purists on both sides—mainline biblical scholars and traditional systematic theologians—find problematic. The fact that Orbis is releasing a fourth edition of Voices from the Margin in 2016, twenty-five years later, is evidence of both the relevance of the postcolonial attention to the third world as well as the unfinished business of postcolonial criticism. There are lots and lots more to be done, postcolonially. Postcolonial Voices from Downunder echoes the Voices from the Margin, and this collection of voices from downunder also comes from a former colony of the British Empire—Australia, and some of its neighbors.

The endurance and transformation (conversion?) of Voices from the Margin over its first three editions locate postcolonial criticism in the company of two modes of cultural criticism: contextual and liberation criticisms. There are other companions, aggravated by other struggles, such as the burdens of discrimination and minoritization because of gender, colour, class, caste, faith, sexual orientation and lots more. What’s important with these various modes of criticism is the shared conviction that postcolonial criticism is not some airy fairy cerebral exercise in textual analysis but interventions (with scriptural texts) from rooted (in context) positions in the process of which interpreters seek some kind of relief (for subalterns). In this regard, postcolonial criticism is an undertaking that is intentional about confronting, hence the second attribute in the subtitle to this collection—Confronting readings.

There are several ways in which postcolonial criticism is con-fronting. First, postcolonial criticism exhibits double conning moves: to contest and challenge (the powers that be), as well as to trick and deceive (in the interests of the minoritized). The postcolonial critic is therefore, so to speak, a con-reader. Second, following upon its conning (doublecrossing) efforts, postcolonial criticism is also a labour in “fronting” in the sense that it seeks to put forward, to make present, and to advocate (for and with the minoritized). The con-fronting components, together, show that postcolonial criticism is not replacement for contextual and liberation criticisms but rather, the crossing of the two. In deed, postcolonial criticism requires dynamic embroiling in contextual and liberating events. And third, postcolonial criticism will be confronting to the gatekeepers of oppressing traditions, cultures, scriptures and theologies. This much is expected. What frustrates me herewith is when some of the minoritized communities [are said to] justify and defend what Audre Lorde called “the master’s tools.” How often do academic, public and church leaders explain that they can’t introduce or support changes and alternative positions because ordinary people prefer the master’s tools? The problem with this is clear, as Lorde puts it: “For the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” Hence the need for postcolonial critics to be all the more confronting.

Third, drawing from the energies of the #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) campaign among African-Americans—BLM motivates communal and international solidarity and action in the exposure of, and in demanding justice for, brutal acts (especially by public officials, including police shooting of innocent people) that disadvantage, assault the dignity of, and murder black people—the confronting components of postcolonial criticism affirms that the lives and dreams of minoritized black peoples and communities matter. Hence the first attribute in the subtitle to this collection—Indigenous matters. The starting point for this collection of postcolonial voices from downunder is the affirmation of the sovereignty, spirit, stories, land, lives, hopes and future of indigenous Australians (see the chapters by Gabrielle Russel-Mundine and Graeme Mundine, Denise Champion and Chris Budden, Neville Naden, Grant Finlay). While Australia is more than its indigenous land, people and heritage, Australia is unfair (thus contradicting the commitment of its national anthem, Advance Australia Fair) without accounting for Indigenous Australia.

What matter in this monograph, are more than Indigenous Australia. The voices ripple toward, and spill over, the borders and politic...