![]()

Crying after Him

Zarephath, a city in Phoenicia, 853 BC

1.

The morning sun warmly tapped the city of Zarephath. Hanno’s mother was watering the flowers outside their home. It was spring. Hanno handed her his freshly filled waterskin and looked around toward the street leading to the central market of the town. It was dusty and empty except for a few old peddlers and some stray mutts. Next door an old woman gathered sticks from a little pile outside her caravan tent. Hanno watched his mother weed the little herb plot she kept near the flowers for a moment. The afternoon sun shimmered on her straight black hair and her perspiring face. Hanno sighed and looked back up the street toward the market. Still nothing. He ducked his head through the front door of his home again. All he saw was the bent figure of his older brother Ethbaal, his straight black hair as glorious as his mother’s. But it was dull in the small room. The only sunlight came from a window by Ethbaal’s writing table.

Ethbaal’s scratching writing utensil on the document in front of him was the only sound in the room.

“Ethbaal?” Hanno said softly.

Ethbaal looked up dreamily from his writing, saw who was speaking to him, and then bowed his head back down. Never spurred, never fussed, he could shame the silliness out of anybody, and silence every gainsayer with his submissive earnestness. No maelstrom in him ever let loose, that Hanno could tell. Ethbaal’s scraggly beard showed he was still quite a young man, only ten years older than Hanno, who was twelve. “But,” Hanno often thought to himself, “he might as well be a hundred years older.”

Hanno left his brother to accumulate enigmas, and wandered back outside and sat down in the dust, resting his head on his hands. He began to draw letters in the dust, practicing what he learned in the little hut school he gathered in sometimes. It was at the old teacher’s down the road near the market. There was a wild rose bush right outside the entrance, and Hanno loved the place.

He had finished his alphabet and was starting to write a story when he saw a shadow come over his carefully drawn letters. Dusty feet stopped just short of the last letter.

“Hi, Hanno, what are you writing? The password primeval?”

“Pygmalion!” Hanno grinned at his friend’s face, which, as always, wore a hero’s winning smile. Pygmalion was like a cheerful and good goblin, right out of an adventure tale told around the fire at night. His amber eyes looked at life’s valleys and hills gaily, curious what would come next.

Hanno glanced down at his story. “Nothing. Only a story about two boys going to the marketplace.”

“How about three boys?” Pygmalion asked cheerfully. As always, he was allied on the side of gladness.

“Three?” Hanno fretted, gazing down at his story, then wiping it away with his dusty feet.

“Yes,” Pygmalion replied. “I met another boy. His father is a merchant, like ours.”

“When can we meet sailors? I’m sick of merchants.”

Pygmalion laughed. “He’s from Samaria.”

“Samaria? There’s no sea by Samaria.”

“Right. That’s why I know he’s not much of a sailor.”

“Okay. Let’s go meet him. Let me tell Ethbaal.”

The boys went through the door into Hanno’s home. Hanno hurried toward the desk in the corner of the room and stood before Ethbaal. Then he turned back and whispered to Pygmalion, “You tell him. He likes you better.”

Pygmalion stood before the desk. Ethbaal was still hunched over his writing. Pygmalion stood by his elbow politely for a moment. He watched until he saw Ethbaal had finished a phrase. Then he said, disarmingly, his voice as soft as if there was a sleeping baby in the room, “Got to finish that copying job before night falls, eh? What is it?”

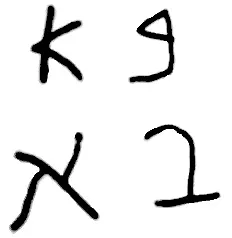

Ethbaal lifted up his head like a lazy tree branch in a soft wind and put his writing utensils down. “It’s Hebrew, Pygmalion.” His tone lured, pleasant and unthreatening. His pale hands were stained with dye.

“Hebrew? But it looks like our language.”

“Yes, Phoenician and Hebrew are related. The alphabets are similar. See?” He drew a picture:

“But what is the writing you are copying?”

“It’s books in Hebrew by Moses.” He smoothed the flat space in front of him carefully, and pushed his hair behind his ears. His eyes were a withstanding metal color, and Hanno remembered his mother remarking that one could just about feel the crush of empires when Ethbaal got serious, which was almost always.

“Moses? We learned about him a lot over the last years we have been in school. So is this where all the stories about him come from?”

“Yes.” Ethbaal studied the boys, somber and inscrutable. “Yes. I suppose you boys don’t remember what life was like before?”

Hanno looked at Pygmalion and then back at Ethbaal. Pygmalion could always get Ethbaal to talk to them. Hanno wondered how he had ended up to be the brother of someone so different from himself. But Pygmalion made himself a kindred spirit of everyone immediately.

“I remember some of the old life,” he said, uncertainly.

“You do?” Pygmalion set his hand on his shoulder. “Then tell us, Hanno.”

“Before the Word of God came to our area, we used to be drunk a lot. I remember stepping in broken wine skins, the distilling intoxications. I remember wetting my feet with wine in the morning after a long night of music and powerful spirits.”

“Right,” said Pygmalion. “And the gossip was terrible, too, leading to longstanding quarrels, even murder.”

“Yes. And very lewd behavior, a wide tract of sorrow,” said Ethbaal. “It’s good you’re spared that.” His eyes were gentle but Hanno still could not pierce a wink behind their surface. “I’m surprised you remember. It was five years ago.”

“I remember when mother’s heart was turned to be right, on the day she first believed in the promises of God. She went to many neighbors’ houses and apologized to them for her hurtful speech and behavior. She took me with.”

Ethbaal sighed, strung up to some impulse, and then released. He meaningfully flicked away a dead fly that had fallen down on his writing. Hanno remembered Baalzebub, a god, “the lord of the flies,” whose wicked teachings they had followed.

Then Pygmalion said, “We’re going to visit a Hebrew.”

“A Hebrew?” Ethbaal lifted his head and scratched his beard. “I suppose you met him in the marketplace?”

“Yes.”

“So last week you brought us to meet your new Egyptian friend. The week before that it was a Phrygian. So now we are going to meet a Hebrew?”

“Yes, from Samaria. But he doesn’t serve the living God. He follows the traditions of men.”

“How do you know, Pygmalion?”

“I asked him.”

“What did he say?”

“I asked him if he follows the pathway that Elijah is on. He said he hates Elijah and so does everyone else in Samaria.”

“Really?” Ethbaal sighed, turning back to his writing, cut off from them as if by a weaver. Hanno stared out the window. He adored Ethbaal, but he never quite believed in him. Outside, the dusty street was still almost empty. Everyone had scattered to their daily labors. Only when the sun began to set would the street fill up with those returning from their washing, their clean...