![]()

chapter 1

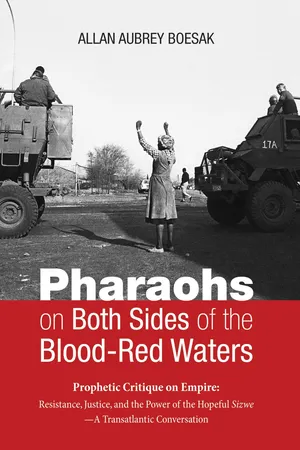

Pharaohs on Both Sides of the Blood-Red Waters

Why We Cry, How We Cry, and Who Can Cry

What do we do when the Pharaoh looks like us?

—Takatso Mofokeng, 2015

“Why We Cry, How We Cry, and Who Can Cry”

In the summer of 2015 Jamye Wooten, one of the young, articulate leaders of the #BaltimoreUprising and Baltimore United for Change (BUC) spoke at the Duke University Summer Institute for Reconciliation. Wooten puts three questions at the center of his talk: “Why We Cry, How We Cry, and Who Can Cry?” What we see on the streets and university campuses is a “cry.” Wooten explains: “Why We Cry” deals with the systemic and structural violence in Baltimore City—the years of neglect, disinvestment and underdevelopment. “How We Cry” addresses the uprising against those ongoing injustices and the community’s response to state violence and systemic and structural violence. “Who Can Cry?” raises the question of whether oppressed groups are allowed to express their pain publicly. “Do blacks or the most marginalized in our society have the right to express frustration, anger, and outrage?” Wooten asks.

But before we can fully respond to these important questions I propose that we consider the broader, more historical backdrop to Wooten’s address. I refer to black theologian Marvin McMickle’s now famous question in his slim but important book of the same title: “Where have all the prophets gone?” It is exactly the question being asked by young people like Jamye Wooten involved in the new struggles for justice today, and not only in the United States. It is of course in the first instance a question about the existence or non-existence of the prophetic church. It is also a question about what happened under the watch of the former anti-apartheid, civil rights struggle activists for the last quarter of a century or more. It is a question about struggles for justice and dignity, prophetic truthfulness and faithfulness, about power and powerlessness, complicity and resistance. As Jamye Wooten spoke about the uprisings in the streets, we, looking back over the last fifty years or so, had been celebrating all sorts of triumphant anniversaries.

It is seventy years after Gandhi led the Indian masses in the Salt March and the sixtieth year of the Women’s March against the Pass Laws on Pretoria as well as the historic Peoples’ Congress in Kliptown, near Johannesburg, the meeting that gave birth to the Freedom Charter, discussed in the Introduction. It is just more than sixty years since the Defiance Campaign, the mass actions of civil disobedience in South Africa that changed not only the character of the anti-apartheid struggle but also the course of our history; sixty years since 17 year-old Claudette Colvin’s brave defiance, followed six months later by Rosa Parks’ decision to sit down on that Montgomery bus and the start of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. We celebrated fifty years of the Civil Rights Act, the March on Washington, the Letter from a Birmingham Jail, just over twenty years of South African democracy, and twenty-five years of the release of Nelson Mandela.

There are also those moments of excruciating trauma that will forever be remembered: almost on to seventy years after what the Palestinians call the “Nakba,” when they were violently driven from their ancestral lands and homes by the Zionist government of the new nation of Israel, in collusion with the vile politics of Britain and France, still not allowed to return; fifty-five years after the Sharpeville Massacre when the police opened fire on nonviolent protesters in South Africa, killed sixty-nine persons and wounded more than 180. It is thirty years after the massacre at Uitenhage in the Eastern Cape when on March 21, 1985, Archbishop Tutu and I preached at the funeral of twenty-seven victims of apartheid police brutality.

It is fifty years after the assassination of Malcolm X and almost as many after the death of Chief Albert John Mvumbe Luthuli, the man who gave such courageous and insightful Christian leadership to the struggle as president of the African National Congress, the historic liberation movement of South Africa. Almost five decades ago Martin Luther King Jr. was murdered. It is forty years since sixteen-year-old Hector Petersen and another young student, Hastings Ndlovu, seventeen, were shot down on the first day in the first wave of the Soweto uprisings that marked the penultimate phase in the anti-apartheid revolution inspired and led by the youth. Almost as long ago the South African police murdered Steve Biko, the bright young mind who shaped and led South Africa’s Black Consciousness movement in the early seventies, dead even before he reached his prime. All this and much more besides have been woven into the fabric of our being and have become the very fiber of our lives, our struggles for justice, our dreams of dignity and hopes of freedom. These moments, in their different ways, all tell us about the road traveled by oppressed people in their quest for justice, freedom, and dignity.

So the cry Jamye Wooten draws our attention to is not a cry out of nowhere, as it were, without reason, rationale or historical context. Neither is it a cry of sentimental helplessness to which society can respond with its customary condescension and then move on as if nothing had happened. It is a cry of disappointment and frustration, of anguish and anger, of defiance and resistance. Marvin McMickle’s troublesome question is exactly the question being asked by young people involved in the new struggles for justice today.

This cry is a cry of grief for the situation in which the people find themselves, and the cry is the announcement that the situation can no longer be tolerated. The cry is raised as critique against the empire and its workings of oppression. Just as in the exodus story the history of liberation begins with the “cry” and “groaning” of the people of Israel, reminding God of God’s covenant, this cry calls upon God to remember the covenant and to “know” the people’s condition. Moreover, Hebrew Bible scholar Walter Brueggemann makes the crucial point that the real criticism of the empire begins in the capacity to grieve because that is the most visceral announcement that things are not right. “Only in the empire,” Brueggemann goes on to say, “are we pressed and invited to pretend that things are all right . . . As long as the empire can keep the pretense alive that things are all right, there will be no grieving and no serious criticism.”

Notice Brueggemann’s choice of words, and one can sense the ever-present threat of the violence that is the empire’s life-blood: the empire “presses”—forces, coerces, pressures. But it also “invites”—manipulating our fears, anxieties and desires, luring and deluding us with promises it never intends to keep, is not even capable of keeping. It is an invitation that contaminates the mind even as it tempts the heart, for it is all pretense. The crucial thing the empire can never do is listen, for listening requires a response. For that, as ancient Israel finally learns in the exodus story and the prophets never tire of telling them, we have to direct our cry to the One who hears. Without the courage to cry out real criticism of the empire cannot begin, and without serious criticism liberative action cannot take place.

The cry that is ringing out across the world is therefore not a plea to the empire, but instead a serious criticism against the empire that is keeping millions in captivity; against the minions of empire in our most intimate midst; against what Wooten calls the “preacher pacifiers” of the empire that pretend that there is nothing wrong, that the “freedom” of the people as defined by the empire is indeed freedom and not new, sometimes harsh, sometimes subtle forms of enslavement. It is a criticism against the way things are, and against the determination of the empire to keep things the way they are.

The young activists of the Black Lives Matter movement intuitively understand Brueggemann’s theological point, underscoring his implied political point, very well indeed. Activist Jamell Spann describes what he calls “respectable politics”:

For these reasons the cry is not a cry of resignation, but “a militant sense of being wronged with the powerful expectation that it will be heard and answered.” Hence the renewed struggles for justice. This renewed engagement with issues of justice and renewed struggles for justice has also called renewed attention to the role of the church in such struggles. It has also raised questions about whether the church is ready and willing to accept a renewed call for prophetic involvement, if not prophetic leadership, in such struggles.

It is not cynicism but bitter experience that has made a new generation realize that the assertion, almost axiomatic in the United States, “Justice for All,” should not be the mindless mantra it has become. Much like post-1994 South Africa’s oft-stated characterization of its democracy—“nonracial, nonsexist, participatory”—it should not be uttered with a period at the end, and certainly not with anything as emphatic as an exclamation mark. It is not a triumphant proclamation, as if these claims were in fact a reality in the lives of all, or even the majority of the peoples of these two countries. It is more the expression of ...