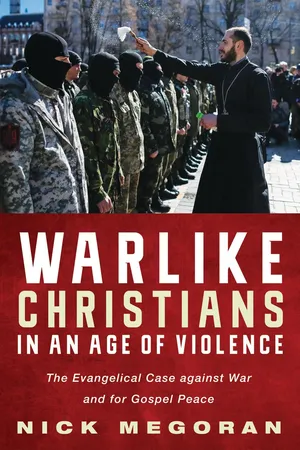

![]()

1

Jesus, Prince of Peace

Hand Grenades in Easter Eggs?

In April 2003, soon after the US and UK began an invasion of Iraq, the sale of an Easter basket in a New York Kmart store created something of a furor. The pretty pink-and-yellow baskets with colorful green-and-purple bows contained not chocolate bunnies but camouflaged soldiers with US flags, machine guns, sniper rifles, hand grenades, Bowie knives, ammunition, truncheons, and handcuffs. The toys were withdrawn following an outcry by shoppers and Christian leaders. Bishop George Packard condemned them as being in “bad taste” and questioned the message sent to Muslims by the mixing of a Christian holiday with images of war.

Most people would, I think, recognize the incongruity of such a striking symbol of violence being used to celebrate the resurrection of the “Prince of Peace” and the triumph of life over death. However, Bishop Packard seemed to overlook an even greater contradiction. He was the man responsible for spiritual care of Episcopalian members of the armed services. That is to say, he and his church supported Christians taking on in real life the role that he condemned in a make-believe world!

The Iraq War threw up many such ironies. It was led by two world leaders, US President George W. Bush and UK Prime Minister Tony Blair, who were arguably the most devout Christians to have held those offices for many years. One of their chief opponents, Iraqi deputy-president Tariq Aziz, was one of the most well-known Christian politicians in the Middle East. Some of the war’s most vocal critics were Christian leaders around the world, from the pope and the archbishop of Canterbury to former archbishop of Cape Town Desmond Tutu. Even Jim Winkler, at the time one of the leaders of George W. Bush’s own denomination, the United Methodist Church, opposed the planned invasion, saying that “war is incompatible with the teaching and example of Christ.” Having repeatedly been refused an audience with the president himself, Winkler led a delegation of American Christian leaders on a world tour to meet leaders from Tony Blair to Russian president Vladimir Putin in an attempt to persuade them to oppose the planned war.

But such disagreement is by no means confined to recent wars. Every ten years the bishops of the worldwide Anglican church gather for the Lambeth Conference. Various conferences since 1930 have endorsed the statement that “war as a method of settling international disputes is incompatible with the teaching and example of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Yet, at the same time, as Herbert McCabe put it, its “cathedrals are stuffed with regimental flags and monuments to colonial wars. The Christian church, with minor exceptions, has been solidly on the side of violence for centuries, but it has normally been only the violence of soldiers.” The Christian church’s position on war is clearly inconsistent, and this confusion inhibits its ability to speak meaningfully into the pressing issues of our day.

The argument of this book is simple. If we turn to the pages of the New Testament, we find no such inconsistency: in fact, the whole life and teaching of Jesus and the apostles is utterly incompatible with warfare, and we are commanded to follow his example. This chapter will outline what that was, while subsequent chapters will discuss some of the difficulties that modern Christians have in accepting it. The book follows Martyn Lloyd-Jones in the biblical understanding that war is a consequence and a manifestation of sin,and Bishop George Bell in insisting that the church’s function in wartime is “at all costs to remain the Church,” the trustee of the gospel of redemption. The Christian (and the Christian’s) response to war is not to fight and kill those fighting and trying to kill us—scripture does not permit that—but simply to be the church! Preach the gospel! This entails working creatively by the power of the Holy Spirit to make peace in the communities and world in which we live—a position that this book calls “gospel peace.”

The importance of this topic of how to deal with war is hard to overstate. As John Keegan said in his 1998 BBC Reith Lectures, war is the chief “enemy of human life, well-being, happiness, and optimism.” It is the great scourge of our age: it undoes God’s good creation; it destroys and deforms people made in his image; it prevents humans from relating to each other as he intended; it is the source of untold human suffering; it disproportionately affects those already most vulnerable, such as women, children, the elderly and the infirm; it inflicts mental and physical disabilities on combatants and noncombatants alike for decades after actual fighting has ceased; it sometimes produces enormous population displacements, wrenching families and communities apart; it creates poverty and inhibits attempts to develop sustainable livelihoods and a just distribution of wealth.

By some scholarly estimates, there were one billion casualties of war in the twentieth century. Nowadays, casualties are often largely civilians. For example, the respected British medical journal The Lancet suggested in 2006 that up to six hundred thousand people had died in Iraq following the US/UK invasion in 2003 as a result of medical facilities being degraded or rendered inadequate because of the war. A belief system that is unable to speak practically to war is irrelevant to this age. Yet in ignoring plain biblical teaching and allowing our thinking to be influenced by culture more than scripture, we have oftentimes done more to excite war than promote peace. As Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. asked, “What more pathetically reveals the irrelevancy of the church in present-day world affairs than its witness regarding war? In a world gone mad with arms build-ups, chauvinistic passions, and imperialistic exploitation, the church has either endorsed these activities or remained appallingly silent.” He concluded, “A weary world, desperately pleading for peace, has often found the church morally sanctioning war.” We have become part of the problem rather than the solution.

Violence more generally is broader than war. It includes violence against women in homes and on the streets, bullying in schools, the racism aimed at minorities, and economic systems that keep some people poor and others rich. Nonetheless the focus of this book is on war and forms of state or nonstate action that resemble it, partially because it is the most spectacular and destructive form of violence, and partially because it is the author’s area of scholarly expertise.

In a hard-hitting book about economic justice, Tim Chester observes that Christians commonly live with two sets of values: one that they espouse in church and another that they demonstrate by how they actually use their money. We have done exactly the same with relation to war and peace. It is said that during the Crusades, mercenaries held their swords above the water when they were being baptized so that they didn’t have to make them subject to God’s rule. In professing to worship the Prince of Peace, and on Sunday morning singing “Crown Him the Lord of peace, / whose power a scepter sways / from pole to pole, that wars may cease, / and all be prayer and praise,” yet allowing ourselves to endorse the possibility of Christian participation in, preparation for, and even celebration of war during the week, we have effectively done the same. The old adage that Christians don’t tell lies but they sing them could not be more clearly demonstrated. It is time that we took scripture seriously and started to preach and practice “the gospel of peace” (Acts 10:36; Eph 6:15), which, I believe, is the only hope for humankind.

The “Roman Problem”

In order to understand what the New Testament teaches about war, it is important to realize just how violent its times were. Jesus was born into a politically turbulent world and grew up with the ever-present threat of violence. Within a short time of his birth, he had become a refugee, as Herod tried to kill him by slaughtering all boys under two years old in the Bethlehem region (Matt 2:16–18...