![]()

1

“I believe . . .”

john hughes

Genesis 12:1–9

Mark 9:14–28

“Lord, I believe; help my unbelief!” (Mark 9:24)

Some of you may have seen the news reports of the 2011 United Kingdom census: that the proportion of people describing themselves as Christian in Britain has declined by 13 percent in ten years: from 72 percent to 59 percent. This is undoubtedly a disturbing statistic Christians in Britain, although we should probably take the advice of the former Archbishop of Canterbury and new Master of Magdalene, Rowan Williams, in his Christmas sermon. He reminded us that the picture is more complex than we think, and that in the end our faith is not based upon success or popularity but upon truth.

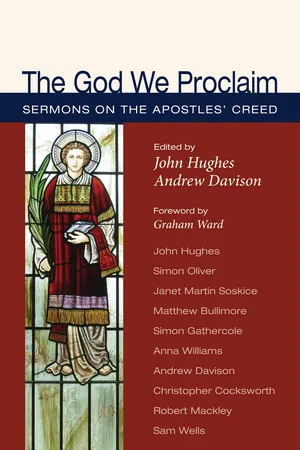

I’ve spoken in chapel before about so-called “cultural Christianity”, which is what I think this statistic is mainly about, but tonight I want to spend some time reflecting on another issue which came up in the debate about the census results: what does belief mean? Any attempt to measure belief comes across this problem: you can ask people what they believe, but sometimes their answers don’t quite seem to add up, or else other evidence makes you wonder whether this is really so. Hence, we’ve seen the National Secular Society and others insisting that most of those who call themselves Christians are not really, because they don’t really believe what they’re supposed to, and so on. Sociologists have even spoken of contemporary religion in the West as being about “belonging without believing”. In the light of all this, it seems worth beginning our series of sermons on the Apostles’ Creed this term by pausing to think about the verb at the very beginning of that ancient universal statement of Christian belief. What does it mean to say “I believe . . .”?

In brief, I want to suggest that most of the ways we think about belief are unhelpful and inaccurate, and should be turned on their head. If we listen to how the language of belief is used in contemporary culture, leaving aside the narrowly “religious” uses, we find that belief is associated with one side of a set of polar oppositions. From pop songs to politicians’ speeches, it is presumed that belief is something uncertain, irrational, private, and inside us (whether in the mind or the will or the feelings). So we say we “believe that something is the case” when we think it is probable that it might be so, but we’re not sure, or when we have a private taste about something. This highly individualist way of thinking about belief has been very influential for the last few hundred years in the West, and it all too easily places belief—at best—in the realm of something to be practised in private between consenting adults, or at worst something childish to be overcome by adults. This was brought home to me when I once asked a child if he believed in God and he replied yes, before moving on quite naturally to talk about whether he believed in Father Christmas and the tooth fairy.

Against this way of thinking, I want to suggest, following a certain philosopher buried not so far from here (Ludwig Wittgenstein), that belief is not so much something that we do with our heads, or even with our hearts alone, but just as much with our bodies, and that, because of this, belief is not just something private or personal, but very much collective, corporate, and public.

In some ways, this is a very Anglican approach to belief, following on from Queen Elizabeth I’s famous line about the impossibility of making windows into people’s souls. It also has a certain psychological plausibility, for which of us can really say that we completely know even ourselves? But I would argue it is also much more biblical. The word for belief in Hebrew is related to Amen, and to the words for truth and trust. When we hear that “Abraham believed God” (Rom 4:3) it does not mean that Abraham had a special opinion about God, or a funny feeling about him: it means he entered into a relationship of trust that shaped the course of his life. Belief is first of all this personal relationship of trust, concerning the whole person. Abraham believing in God is not just about something inside him; it’s about a relationship that makes him get up from Ur and go somewhere new. “By their fruits you will know them”, says Christ (Matt 7:16). If you want to know what people believe, then it’s better to look at what they do rather than what they say, or even think. Belief is about the shape of an entire life.

But what about certainty? Belief does seem to have something to do with uncertainty, or else why would everyone not just agree about it? One of the most famous verses of Scripture on belief could seem to support this view by contrasting belief with the certainty of sight. This is when the Letter to the Hebrews speaks of faith as “the substance of things hoped for, the assurance of things not seen” (11:1). But surely the contrast here is more like the difference between being on a journey and the end of that journey. The uncertainty of belief is more to do with the fundamental glorious openness of life itself, since the nature of life is such that we can respond to it in different ways, and the differences between these ways are not something that could ever be finally resolved in this life. This is precisely why a proper understanding of belief should support the freedom of people to hold differing beliefs rather than trying to coerce everyone to believe the same thing. Christ calls people to follow him because we have the freedom to do so.

But this openness is not quite the same as saying that belief is something optional, a niche interest for those who are into that kind of thing, like jogging or vegetarianism: for if belief is about what you do with your body, the shape of a life, then simply to live is to believe something, whether we realise it or not. Our lives are always already oriented towards certain views of the world, implicitly presuming certain things to be of value or not, whether we chose these directions or not. The question then is not whether you will believe or not, but rather in what, and whether you will realise or not! And when we think of belief in terms of the underlying commitments that shape a life, we realise that, while in one way belief may be characterised by less certainty than my knowledge of dull facts, such as the existence of a table in my study, in other ways belief concerns the things held to with most certainty. Most facts are generally rather uninteresting things to die for, but not beliefs!

All this does not mean that belief is something irrational. It may be beyond straightforward logical demonstration, it may be a matter of the whole person rather than something narrowly intellectual, but belief should not be the end of intellectual curiosity, criticism and thinking. Much more could be said about all this, but suffice it to say that being a theologian would be very dull if it were not so! The reason we have theology in universities is because belief is not the end of questioning and understanding, but rather its beginning. And I think this is true not just for theologians, but for most Christians, who don’t want to leave their brains at the doors of the church. The relationship with God that we call belief is, like any relationship, a constant journey of understanding. I rather like the picture of Jacob wrestling with the angel from our Old Testament reading as a symbol for this side of faith. The psalms and the book of Job are other great places to look for examples of belief as a pretty robust and honest relationship.

But all this can sound rather exhausting, as if belief is a rather dysfunctional relationship, all about hips getting put out of joint (as happened to Jacob). Perhaps the most surprising and important thing about belief is when we discover that it is not in the end all about us at all. We might contrast the comment that people sometimes make about their faith “coming and going”. I think this must be what they mean: that faith is like a feeling, which sometimes they get and sometimes they don’t, or that it’s like an act of will which sometimes they can manage and sometimes they can’t. This is the real core to the modern individualistic view of belief. “I believe” becomes here some great act of self-projection, an extension of our will. And yet belief in the Scriptures is much more like a gift, something we simply receive. I think this is usually true of most relationships—however hard we work at them, we can’t make someone love us. Indeed friendship and love is usually something like a gift that releases us from these rather pathetic strivings. The theological word for this is “grace”.

Mercifully, we do not all have to sit down and make up our own creed from scratch. The Creed is given to us, like the church itself, because we do not believe on our own. Belief is bound up with belonging, because it is something like inhabiting a landscape, exploring a vision, and we do this in the company of others. Ultimately, however, belief is not just something we receive from other humans, from the church. If belief is a relationship with God, then that relationship is a gift which he offers us, rather like the outstretched hand Christ offered to the sinking Peter on the Sea of Galilee. The prayer of the father of the child in our New Testament reading tonight captures this paradox well: “Lord I believe, help my unbelief!” We start off by thinking belief is all about us, something we do, and then discover that it is a gift to be received, something for which to pray. Some days we may feel like a mighty warrior of faith; other days we may feel we have less faith than a mustard seed. Some days we may think we understand it all; others we may feel completely mystified. But it does not matter. The Christian faith, which the Apostles’ Creed summarises, is not all about us. It is about the God who created all things and who invites us to explore the infinite riches of the relationship that he offers us in Jesus Christ. To him be glory and praise, now and forever, Amen.

![]()

2

“In God the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth”

simon oliver

Exodus 3:1–15

John 1:1–14

In 1692, an ambitious clergyman, Richard Bentley, later a controversial Master of Trinity College (he endured a thirty-year feud with the College’s Fellows), was commissioned to deliver the first Boyle Lecture. Robert Boyle, the great natural philosopher, had died the previous year. He endowed a series of lectures for the discussion amongst learned men of the existence of God. In preparing his lecture, Bentley wrote to the Lucasian Professor, Isaac Newton, to ask about the usefulness of his great work, Principia Mathematica, for the defence of the faith. In a now oft-quoted letter, Newton replied, “When I wrote my treatise about our Systeme [the Principia] I had an eye upon such Principles as might work with considering men for the belief of a Deity and nothing can rejoice me more than to find it useful for that purpose.” In the same letter, Newton states that he was forced to ascribe the design of the solar system to a voluntary agent and, moreover, “the motions which the Planets now have could not spring from any natural cause alone but were impressed by an intelligent agent.”

While Newton wrote far more about theology and prophecy than he did about natural philosophy, it is his physics that transformed our perception of the universe. Nevertheless, Newton was part of a wider pattern that emerged during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in which a particular way of understanding creation and divine providence became dominant: the view that God had designed the universe. This reached its most influential expression in William Paley’s Natural Theology, published in 1802. It’s often thought that the view that creation is designed is dominant throughout the Christian, and indeed philosophical, tradition, extending all the way back to Plato’s Timaeus written in the fourth century BC. It’s striking that New Atheists’ attacks on religion tend to assume that, if we are to talk of God’s act of creation, we must think in terms of God designing the universe in much the same way as I might design a car. Newton pictures creation in just this way: the matter of the universe is essentially passive and God decrees the laws of nature in the language of mathematics and then ensures that every element of the universe obeys the laws. Much as a monarch might govern a kingdom via the force of his legal decrees, so God governs the universe. This is apparently how we are to understand the first line of the Creed. To profess that God created heaven and earth is to say that God designs the universe: there is a direct similarity between the intentional human design of an artefact and God’s “intelligent design” of the cosmos.

In fact, prior to this “theological revolution” of the seventeenth century onwards, the Jewish, Christian, and Islamic traditions do not understand divine creation in this way. There is a very striking consensus amongst religious thinkers over fifteen hundred years that if we are to speak ...