![]()

1

Living into My Image

Devan Stahl

Living in Tight Spaces

Pressure builds inside my chest as if it is being pushed from both the front and back. My breathing is shallow and restricted and I force myself to take long, deep breaths. A sensation of restlessness begins in my chest and slowly moves out to every inch of my body. Suddenly I feel like I am vibrating, as if at any moment my whole body is going to rip apart. I want to move, I have to move. Not moving requires holding back all the forces in my body that are desperately pushing outward. If this does not end soon I am going to break. Tears well up in my eyes, but I desperately try not to open them. Small streams run down my face and make my skin itch. Normally I would open my eyes and fan them, but I resist. I squeeze my eyelids tighter to drain the fluid. I know I shouldn’t, but I open my eyes in an act of defiance. Now I see what I was dreading: the dark narrow walls of the tunnel just inches from my face. My eyes begin to cross as they try to focus on the crossbar attached to my head restraint. I quickly close my eyes again.

I never knew I had claustrophobia until I began receiving regular MRI exams. It takes all of my will power not to yank out my IV and scramble out of the machine. Of course, I agreed to be in that scanner; I agreed it was best for my health to subject myself to the scan and I know that if I stop in the middle, I will be forced to start the whole process over again. I am a willing participant in this uncomfortable process because it is necessary for my “medical treatment plan” and my doctor ordered it. I am chronically ill and I require constant monitoring. I have never asked to be sedated, partly out of cowardice and partly out of arrogance. I do not like asking for drugs. I should learn to conquer this feeling. I should learn to be more meditative. Perhaps I can turn this fear into an opportunity for contemplative spiritual practice. No luck so far with that particular ambition.

The whole MRI production begins at the hospital, a fine place to be if you work there, but a dreadful one if you are ill. After filling out my preliminary intake forms, I am asked to undress and put on a hospital gown, two if the gown is flimsy. Better safe than sorry. I have found the standards for the clothes I can wear during the exam vary depending on the lab. I once had a rather awkward conversation with a radiology technician about my bra. He was an older, slightly grizzly looking man who introduced himself by asking where I bought my bra. In my vulnerable position, I did not immediately ask why he wanted to know. I assumed he was a professional with a point. Apparently, Victoria Secret bras use a plastic underwire, which is perfectly fine in the MRI scanner. Regardless, he informed me, a metal underwire, like the metal zipper and button on my jeans, would vibrate during the exam, “which some women rather enjoy.” This comment left me in the rather awkward position of having to decide whether I should leave my clothes on and allow this man to think I was “enjoying” the exam, or take them off and feel cold for the next two hours. My advice: leave your clothes on if you can. Hospitals are cold and the inside of an MRI scanner is no different. Do not allow perverted old men to convince you not to take your clothes off, as counterintuitive as that may sound. It never ceases to amaze me what some men think is appropriate to say to a young female patient.

After I change, I sit on a locker-room bench, waiting for a technician to prepare the machine, finish with the previous patient, or tell jokes about my undergarments. I can only guess what they are doing behind those doors. When I finally enter the lab, a tech fits me with an IV so he can later inject me with contrast dye. I have very small veins and when I go for blood draws, nurses often require several attempts to strike just the right place. The nurses who know me give me a heating pack and use infant needles. Radiology technicians have no such sensitivities and I have been known to faint or become nauseous after an IV insertion. I am not afraid of needles, so the immediate physical reaction I sometimes have to an IV is frustrating and somewhat embarrassing. One prick of that large needle and the room begins to spin. Thankfully, I have never vomited on a tech and I pride myself on this feat.

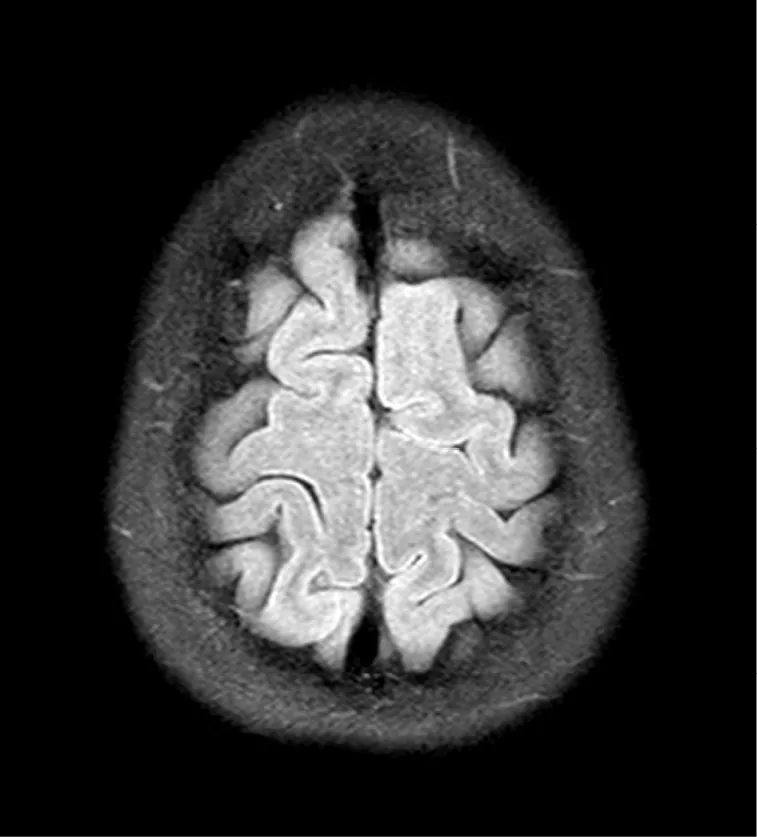

When I lie down on the scanner, the tech secures my head into place so I cannot move it. It is terribly uncomfortable and my neck is usually sore after the exam. Someone hands me a buzzer in case I need to speak with the techs, which I have never used, and earplugs to drown out the noise of the machine. There is no drowning out the noise of the loud machine, and worse still, the noise it produces is completely arrhythmic. There is simply no chance of making a song or jingle out of the pulsing, erratic sounds. I have tried. There is no sensation I can escape into during the process. I try to avoid seeing, hearing, touching or even smelling anything in the narrow walls of the scanner. The best I can do is escape into my own thoughts, but given the reason for having the scan in the first place, my thoughts can quickly turn anxious. The whole process can take over two hours and still longer if I move to adjust my aching body. The result of my efforts is hundreds of computer-generated images of my body, from my lower spine to the top of my head.

Living in Numbness

I vividly remember the first time I ever laid eyes upon my MR images. I was twenty-two and had just finished my first semester of divinity school in the buckle of the Bible Belt. I had left my conservative denomination for one that allowed female clergy and I was feeling empowered. I was even beginning to reconsider ordination, a dream I had abandoned at the age of fourteen when my minister told me that, while I was very bright, God did not call women to leadership in the church. Perhaps God wanted me to marry a minister and I was getting my wires crossed. Then and now, I find all the “calling” metaphors in church-talk confusing; I have never heard God’s voice directly. Embarrassed to admit this fact, as I believed it revealed a lack of faith on my part, I agreed my pastor must be right. Only after studying religion in college did I learn that many Christian denominations ordain women and they managed to do so reading the same Bible and without crossing out a single line of Scripture.

I chose to go to Vanderbilt Divinity School because of its progressive reputation. I soon acquired a group of diverse friends with a variety of opinions and belief systems. I was having a blast. Contrary to popular opinion, the South is full of open-minded people and seminarians can be some of the most socially progressive people you will ever meet. My colleagues were passionate, energetic, and they wanted to change the world. We rallied for marriage equality one week and held Southern-style revivals the next.

Then my feet went numb and the fun stopped. A sort of tingling sensation began at my feet and started to creep up my legs slowly. It almost felt as if my feet were asleep, but the tingling lasted for days. Although the lack of sensation I experienced allowed me to wear my highest heels without discomfort, I figured I should probably go to a doctor. At twenty-two I was naïve, but not grossly irresponsible. After attempting to make a hospital appointment only to be told I would have to wait eight weeks to see a doctor, I drove myself to a walk-in clinic. Unsurprisingly, the physicians there had no idea what was wrong with me. The sensation slowly dissipated and within a few weeks had completely vanished. I spent the following months seeing a variety of physicians who all had their own tests to perform. The process was annoying and expensive, but I anticipated coming out of it just fine. I was a healthy, if somewhat clumsy, twenty-two-year-old, and I never expected anything was seriously wrong with me. More than anything, I was annoyed at the constant traveling, waiting times, and mundane questions the physicians asked.

Three months later I was given my first MRI scan and referred to a neurologist. It took the neurologist all of thirty seconds to diagnose me after examining my scans.

“It’s MS!” he declared. I was speechless. MS? I did not see this coming. My mind raced.

How could he tell? What is he seeing? What is going to happen to me? Didn’t I see this coming? Didn’t I do an Internet search on this? Didn’t the other doctors tell me I was going to be all right? Were they lying? Did they know? Did they suspect? How can he know I have a devastating illness just looking at those gray blobs? What is MS? It’s bad . . . it’s neurological . . . it’s debilitating . . . wait, I know someone with MS . . . a woman who goes to my church has MS. Every Sunday she comes and goes in a van because she is a quadriplegic.

A lump begins to form in my throat. I know this feeling. I hate this feeling. I know what is coming and I know I cannot stop it. I used to hate crying in front of other people (now I only exceedingly dislike it). I was trying to cultivate the habits of a strong female leader and at twenty-two crying made me feel powerless and pathetic. My rather insensitive physician pushed a box of tissues my way without taking his eyes off the computer screen containing my MRI scans. I tried to pull myself together.

“How can you be sure?” I managed. He looked confused. “I’m not sure what you are seeing in those pictures,” I followed up.

“I’m a specialist” he assured me, in his most proud and patronizing tone. “I know what I am looking for.”

My body shrinks in and I stare at the floor, then back at the computer, then back at the floor. All the energy leaves my body. I have no more questions. I am empty. I curl up in the fetal position and a large needle is inserted into my spine; my diagnosis is confirmed. I have multiple sclerosis.

The significance of this event took days to settle in. I was finally beginning to accept and appreciate my womanhood—including my female body—and what it might mean to be a strong feminist, and the diagnosis felt like a setback. Illness and disability would surely make me weak and make my goals in life, already lofty, harder to achieve than ever. What if I could not walk? What if I went blind? What if I lost my memory and could not be a scholar? And though my young feminist self was loath to admit it, I could not help but think, “Will anyone ever want to marry me or have children with me?”

I was unsure how to talk about the diagnosis; I had no voice for it yet, so instead I read. I read stories and memoirs from women living with MS, and I read theologies of disability to learn how others reconciled their faith with their present embodiment. After some time I began to out myself to my friends and family. I wanted support, but I dreaded being pitied, which seemed inevitable. To this day, I still struggle with who to tell about my illness and when. I do not bear any of the overt, physical signs of illness and so it is easy to avoid the subject. My illness has become a large part of my identity, however, and I cannot hide it away. People always expect you to be sad or strong about illness. They want you to fight it and keep it distant from yourself. People want you to persevere through it to g...