eBook - ePub

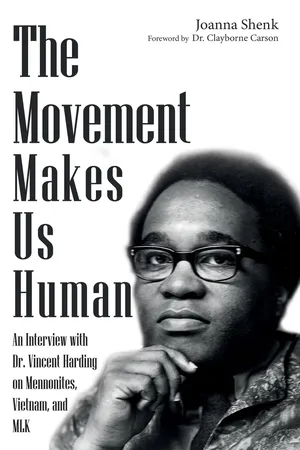

The Movement Makes Us Human

An Interview with Dr. Vincent Harding on Mennonites, Vietnam, and MLK

- 134 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Movement Makes Us Human

An Interview with Dr. Vincent Harding on Mennonites, Vietnam, and MLK

About this book

How is it that the person who created and defined the field of Black Studies and drafted Dr. Martin Luther King Jr's prophetic Beyond Vietnam speech needs an introduction, even in movement circles today? In this provocative and poignant interview, Dr. Vincent Harding reflects on the communities that shaped his early life, compelled him to join movements for justice, and sustained his ongoing transformation. He challenges those committed to justice today to consider the enduring power of nonviolent social change and to root out white supremacy in all of its forms. With his relentless commitment to education and relationship-building across lines of difference, Harding never doubted the capacity of people to create the world we need.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Movement Makes Us Human by Shenk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

History of Religion1

This Is Not a Story about Vincent and Martin

The Southern Freedom Movement

In his twenties, while serving as a copastor of a Mennonite church in Chicago, Vincent Harding became interested in the black-led movement for justice in the South. By the early 1960s he had moved to Atlanta with his spouse, Rosemarie, to join the movement and coordinate the first interracial community house in the city, Mennonite House. In this first chapter we explore his formation in the movement, how Mennonites played a key role in his relocation to Atlanta, and why it was that he came to write the “Beyond Vietnam” speech.

Joanna Shenk: How did you develop and deepen your relationship with Dr. King? He had initially invited to you to work in the South. Were you in conversation with him as you prepared to move to Atlanta? Due to your relationship, did you decide to locate Mennonite House near the King’s home?

Vincent Harding: That’s a big one.

Yeah, I think that’s four questions. [laughing] And maybe one way to narrow it, having put all of that out there, is when we were talking earlier and you shared the moment when Dr. King had explicitly invited you, saying, “Come and work with us in the South. You Mennonites understand what we’re doing.” What came after that invitation? I’m sure we could talk for days about that. Did you call him up and say, “Hey, we’re taking you up on your invitation!” Or, at what point did he know you were coming to join what was happening in Atlanta?

I think that what our visit to the South did, for the first time—the four guys and I, the visit specifically to Martin’s house—was to give great concrete specificity to the movement in ways that we had not known before.

Being with Daisy Bates in Arkansas, in Little Rock. Being in the state of Mississippi in the light of all that Mississippi meant, particularly exemplified by Emmett Till. And then being in Alabama and with Martin King, being specifically in Montgomery. All of that gave great concreteness to what I had known generally about, but was not in any way a deeply knowledgeable person, up to that time. It was something that I had paid attention to more and more and more, but it was this experience in the South that sharpened and opened me.

I don’t think there was any calling of King [on the phone] but, as I have discovered in my papers, there are a lot of things I don’t remember. So I am very careful saying I don’t think that there was any calling of King.

What I am aware of is that after that kind of invitation . . . and it was not an invitation to come to Atlanta because he was in Montgomery at the time; it was an invitation to come south and work with the movement.

For better and for worse, King’s major activities were never in Atlanta. That’s important to know and understand and realize. That was the base of his organization, and why it was not at the same time the major focus of a campaign of desegregation is a whole story in itself, into which this is not the place to go now.

It’s important to know that King was not inviting me to Atlanta. He was inviting me to come and participate in that movement in the South, which for him and for all of its participants was not tied to any one specific place. The movement in the South—the movement of which King was the best-known spokesperson and representative of—was much, much, much more than King. And it’s very important to make it clear that when my late wife, Rosemarie, and I went south we were not just going to work with King.

The movement was something that was happening in dozens of communities, all over the South. There was no one place, no one base. It was something that was spreading like wildfire, all over the South. And so to participate in it one had to at least be aware of that fact—that this was something that was grounded in the experiences of local people in local places all over the South, and not, in a sense, coming under a kind of general “living in Atlanta.”

When we decided—that’s a funny word, I’m not sure that that’s the best thing . . . from the time that I went south and the movement became more of a reality to me, shortly after that, I first met Rosemarie. And within a year at most after we met, we knew that we wanted to be connected and eventually wanted to be married. And always in the midst of our conversation about our own connections was the whole question of who we were and what we meant to the Mennonite community at large, in this country.

Because we were, in a sense, representing this kind of, what might be called an exotic brand of being Mennonite, there was a lot of attention on us, for better and for worse. But in both of our cases we were not Mennonites floating out in the air; we were Mennonites grounded in some very specific communities.

In Rosemarie’s case, before I met her she had become a deeply engaged member of Bethel Mennonite Church on the west side of Chicago, of the General Conference Mennonite Church. It was only after I became part of Woodlawn Mennonite Church—no, she was Old Mennonite and I was General Conference—that I even heard of her and eventually met her. I was grounded at Woodlawn. It was from Woodlawn that the five of us men made that journey to the South, partly because we were grounded at Woodlawn, where we were trying to understand what it meant to develop an interracial Mennonite church.

In those days, of course, interracial was essentially white and black. That was our context. I think it’s pretty safe to say it was when I came back from the South, and eventually in the continuation of my work as a part of the pastoral team at Woodlawn, when I then met Rosemarie and we began talking about our life together and what it would mean for us and the Mennonite church to live a life that had something to do with the struggles around race in America.

When we knew that that clearly had to be one of our purposes of being in the church—to be witnesses in some way or another to the possibilities of life across racial lines and to encourage people to try to build those kinds of communities . . . we knew that was part of why we were in the Mennonite church.

And Rose probably discovered that more than I did, before I did, because before I met her she had gone to Goshen College, graduated there. She had been deeply immersed in a lot of the Anabaptist discussions there. She had met John Miller and some of the people who would eventually form the Reba Place community. All of that happened before she met me, and before I met her.

One thing I do remember is that some time during my time at Woodlawn, and I think after I met Rosemarie, some of the folks from the Freedom Singers of the movement came to Chicago. Bernice Johnson Reagon and her husband and Bertha Harris and others, some of them came, as they were doing in those days. This would be late 50s, early 60s. They came to Chicago to tell the story of the movement, partly through songs, partly through testimony.

These folks were not performance singers. These people were those who were singing the songs of the movement because they themselves lived that movement and shaped their songs as a result of their life in the movement. These were authentic people who were telling authentic stories. I think for both Rose and me it was at one of those gatherings that we heard both the songs in that powerful way and the stories. And that was one of the moments, I suspect, that we began really wrestling with, “What does this mean for us?”

And increasingly we were asking the question, “What does it mean for a church,” as Martin King said, somewhat more kindly than he should, “that you Mennonites, you know about this matter of nonviolence?”

Rose and I were asking, “What does the Mennonite teaching about peacemaking mean, especially, and discipleship and living in true belief, that we are children of the loving God—all of us, especially those of us who claim to be followers of Jesus?” What did it mean for us to be part of such a church in the midst of the struggles that were really rising in the South?

And with, I guess, for me the memory of that statement by Martin and that invitation, and for Rosemarie the very clear teaching of some of her beloved professors at Goshen—what did it mean for us to be black in the Mennonite church, an overwhelmingly white church? And to recognize that part of our responsibility might be to share with the Mennonite church the significance of the movement for people who claim to be disciples of Jesus.

So we began talking a great deal—more than some of our sisters and brothers were interested in having us talk, but at the same time others encouraged the talk. We began talking a great deal about how should the Mennonite church be related to the struggle in the South. And we realized that there were some factors that had to be addressed.

One of them was this deeply ingrained historical experience of Mennonites of having gotten into a lot of trouble in Europe by trying to be disciples. And running into trouble with the authorities, and in some cases losing lives because of what they said they believe, including refusal to serve in military, but wanting to be peacemakers.

We recognized that there was a whole tradition that at least the Swiss Mennonites referred to as the stillen in em lande—“the quiet in the land,” those who don’t make waves. Because if you make too many waves you could be arrested at least, and you could find your life lost at most.

They were looking at a movement in the South that was built on defiance of the laws. And so for a lot of people that was a hard one that they were trying to figure out: how to put that together with the dangers that they had gone through [historically] and that many of them did not want to go through again in this country; how to put that together with the great understandable but terrible temptation that white Mennonites had to hide behind their whiteness, and to thereby keep themselves separated from the sufferings of those who were not white in America; and how to deal with the fact that there were some Mennonites that had bought into American racism and who were, whether they knew it or not, living out that racism, either in terms of their desire or their willingness to be as separate from black people as possible, or through their belief that there was something really superior in whiteness.

So all of those things were part of what we were talking about with ourselves and with others. “How do we take this on? How,” again and again we were asking, “does a church that claims to be a peacemaking church, how does such a church look at the war going on in the South? Does it simply say, ‘That has nothing to do with us’?”

And so we began increasingly saying, “Mennonites ought to be in the South in some way or another.” Now, of course, quiet as it’s kept, there were Mennonites in the South. There were ...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: This Is Not a Story about Vincent and Martin

- Chapter 2: Identifying with Those Who Did Not Always Know How to Identify with Me

- Chapter 3: Standing at the Heart of the Black Community

- Chapter 4: The Question of Nonviolence

- Chapter 5: What We Have Messed Up, We Can Clean Up

- Chapter 6: Reclaiming What’s Natural

- Chapter 7: Closing Prayer

- Conclusion: Where Are We on the Journey of Becoming Human?

- Appendix A: Timeline of Vincent Harding’s Life

- Appendix B: Articles by Vincent Harding