![]()

1

2009 aND tHE NEW IMAGE

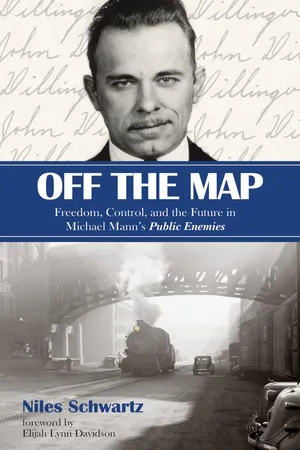

Released to mixed reviews and middling box office success in July of 2009, Michael Mann’s Public Enemies is retrospectively one of the most curious and significant films in cinema’s migration from analog to digital. Mann pioneered HD cinematography in the mainstream with Collateral (2004) and Miami Vice (2006), building on the new technology aesthetically and grounding its use on practical photographic utility. In Public Enemies, this hyperkinetic video approach within a 1930s-period frame troubled many critics and viewers. Set on an impressionistic canvas following American outlaws in flight from encroaching law officers, Public Enemies is a great filmmaker’s bold big-budget experiment of film—or video—form, its reflexive formalism harmonizing history in a strange new sound, aspiring to conjoin the mythos of John Dillinger (played by Johnny Depp) with politics and culture, history and celebrity, film-making and film-watching, all in the gorgeous matrix of a spellbinding new age.

Public Enemies emerged at a cinematic fulcrum point. Filmmakers had made the leap from analog to digital some time before, Mann experimenting at the forefront with a few scenes in Ali (2001) and then more comprehensively in his short-lived Los Angeles TV show Robbery Homicide Division (2002), which served as a sort of small-screen demo for the widescreen canvases of Collateral and Miami Vice, the former winning several year-end awards for its cinematography. While other technophile directors like George Lucas, David Fincher, Francis Ford Coppola, and Steven Soderbergh advanced their aesthetic on this new template, Mann’s distinctly idiosyncratic use of HD cameras rattled viewers with its alien video-ness, explicating to viewers that they were perched on a separate filmic architecture that may require a new way of seeing. Branching off from a new visual apparatus was a different modulation of not only editing and sound, but also Mann’s increasingly paratactic approach to his characters, as their detailed backstories, while provided by the director to his actors during pre-production, diminished textually as the bodies in his digital frame were lassoed into the shackling grid of binary data as data, vaporous existences and stories struggling to materialize in an accelerating cyberspace vacuum. His artistry expresses a paradox of visceral sensory verisimilitude that tilts toward—without wholly embracing—baffling avant-garde pure cinema abstraction feeling aesthetically closer to David Lynch (INLAND EMPIRE), Albert Serra (Honor de Cavelleria), Jean-Luc Godard (Film Socialisme, In Praise of Love), and Abbas Kiarostami (ABC Africa, Ten, Shirin) than other big studio digital filmmakers. His films tacitly prompt a formal dialogue where style generates substance, while the final products are still part of the big studio mass-cult entertainment machine. The resulting films are replete with earnest sociopolitical and spiritual inquiries. Public Enemies projects the future into the past, and poses questions concomitant with the arguments and speculations about film, politics, and human beings that were part of an urgent philosophical movement.

Public Enemies was released before digital had usurped 35 mm projection booths in theaters and the exhibitive delivery package would change over, kicking longtime projectionists and their flickering equipment out of theaters. It was also just a few months before the paradigm would perhaps undergo its most significant popular shift with the release of James Cameron’s Avatar. Cameron used the digital tools to create a fanciful Edenic hyperfirmament, a collision of the real and virtual. Avatar was a $500 million gamble that sparked a revolution, ensuring that most blockbuster releases would have 3-D exhibition, signaling that the possibilities of this new world, Avatar’s planet Pandora doubling for the future of cinema, were limitless. With the real-world tactility of Public Enemies and the full-on graphic design of Avatar, Mann and Cameron could be seen as the new cinema’s juxtaposed figureheads, speculating how the image is changing and how we change along with it, their dual approaches incorporating in one case the historical mythos of master criminal and folk hero John Dillinger, and in the other an archetypal myth framework building on extraterrestrial imagination. Both films are about private, hidden lives eluding the hampering systematic control of a surveilling panopticon, the audience’s interaction part of the experience: we reflect onto John Dillinger seeing himself and Billie Frechette in a gangster melodrama at a movie theater, and we double for Avatar’s paraplegic protagonist, Jake Sully (Sam Worthington), who escapes into a pixelated 3-D alien planet.

*

Avatar’s futurism resonated in 2009 with its wounded war vet protagonist, environmental concern, and references to gaming and social media. But Public Enemies’ aesthetic conjoins the quandaries of contemporary cyberspace and globalization with the cultural problems of its 1930s setting, a time when philosophers were concerned about the power film had over the public, as burgeoning political ideologies vied for control of nations.

Central to that discussion was Walter Benjamin’s landmark essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” which tells us that cinema is necessarily bereft of the “aura” of other arts. Subject to photographic replication, motion pictures were distributed across the globe in thousands of prints, unspooling several times a day and consumed as frivolous escape for audiences, who would have a substantially different interaction with them than an ancient Greek would have with a sculpture. Ancient art would often have a cultic, religious role to play. There is also the question of utility and aesthetics, such as with architecture. Photography changed so much because the optics of the camera were so different from the human eye, and so a photographic replication of a painting would essentially be a different encounter from seeing something unmediated in a here-and-now context. The movies could meanwhile liquidate history through propaganda and be a great tool in subduing and controlling masses of people.

The Frankfurt philosophers, with whom Benjamin was associated, were Marxist Jewish intellectuals from Germany, alert to how the government used media to control populations. Fascism aestheticizes politics, the viewer not “clobbered into submission,” as Benjamin puts it, but appeased into a volitional submission, which, as Kolker says in his analysis of Benjamin, typically connects “out of the most profound and uninformed aspects of a culture’s collective fears and desires,” and “confirmed and reinforced the basest instincts of that culture.”

Even the most well-intentioned films are thus problematic as products of this apparatus. Public Enemies was mass-produced art, shot and edited digitally, distributed to thousands of multiplex movie theaters, and starring two big-name movie stars (Johnny Depp and Christian Bale). Yet it’s conscientious of how media semiotics affect and control people, simultaneously expressing the human need for freedom. It’s a theme familiar to Mann, whose The Insider (1999) opens with Lowell Bergman (Al Pacino), a mass media (CBS’s 60 Minutes) journalist who we learn idolizes Frankfurt philosopher Herbert Marcuse, blindfolded in Beirut. The first image is Bergman’s point-of-view, an extreme close-up on stuttering cloth. The director controls what we see and there are ramifications to how we process images. How does a big budget film hold onto its integrity in the Hollywood apparatus? Or a journalist at a major network? Or an audience member working a 9-5 job, dependent on an income and insurance? In each case, the subject compromises out of necessity, yet treads a thin line. The Insider and Mann’s subsequent feature Ali (2001) are about men threatened by images imposed on them, and who in retaliation work to subvert those images, subjective individualization working against insurmountable and imperial zero-sum axioms.

In Public Enemies, John Dillinger interacts with mass-art. He’s a romantic, projecting himself into that media through the force of his imagination and scripting a romance with himself in the lead role, his spirit commingling with Billie Holiday’s voice on the radio and Clark Gable’s countenance at the cinema. Many people have a powerless, automatic response to the media they encounter. Benjamin writes of the possibility of the viewer having an active, intimate dialogue with the art. He writes, “The progressive reaction is characterized by the direct, intimate fusion of visual and emotional enjoyment with the orientation of the expert.” Unfortunately, critical engagement is less likely in a mass consumable like a movie, where the audience at large can dictate one, individual reaction. How is the viewer activated instead of ossified? Can John Dillinger, and we, truly have that intimate dialogue with this mass-market, replicated product?

Contemporaneous with Benjamin was the intellectually enlivening dialectical cinema sense postulated by early Soviet filmmakers, such as Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov, cited by Mann as being two of his primary influences. There’s a dynamic mechanism to art that affects the viewer, rooted in formal engineering, the same way a poem gets its charm from the construction of meter and accents of vocabulary, or in painting how the eye follows one element which creates an impression, which then collides with a second element in the painting; in cinema, the filmmaker uses the elements of image (including shape and spatial relationships) and montage. Cinema’s technological ingenuity is not empty mechanics working to soothe us as docile machines, but has the potential to reach into hearts and minds, affecting change through dialectical methods of thinking (and, for the Soviet theorists, revolution, as workers of the world are united by seeing)—a new way of thinking and seeing the world outside of the theater. The camera eye may not only be imitating the human sensory process, but, as Vertov saw it, it was independent from it, capturing something we couldn’t see. How are our sensory and intellectual processes evolving in imitation to the camera and montage? Can a cinematic method enliven us and enrich life, beyond entertaining us and serving as an escapist portal? Mann is one of many filmmakers walking the tightrope of popular entertainment and personal expression, administrating over immense productions with complete control. Watching his films we struggle with the problem of reconciling the agent of mass production in a capitalist economy and romantic notions of the auteur.

Those creative idiosyncrasies, out of sync with the bulk of movies in whatever genre (action, biopic, historical), have provoked some industry analysts to wonder why he is still allowed to wield such power. That his unparalleled technique and vision has endured for so long is a glowing affirmation of how art works in the mainstream. As an information age filmmaker, he considers serious Frankfurt School questions regarding the digital curriculum, where the speed of life sprints toward paralyzing seizure. How does the individual remain grounded and hold onto integrity in such a hyperreal, evanescent—vast with information and yet too fast to plum muc...