![]()

1

Introduction

High Honors

In the spring of 1924 the abbé Henri Bremond received the greatest public honor his country could bestow on a historian and writer. Having completed to popular acclaim, but mixed scholarly reviews—even outrage in some quarters—the first six volumes of his Histoire littéraire, his projected Literary History of the Religious Sentiment in France from the Wars of Religion down to the Present Time, he was elected to membership in that revered bastion of elite French culture, the Académie française. He had made it to the top.

The journey, however, had been a rocky one, and he had been an unlikely candidate. His Provençal roots marked him as a regional and provincial character; his early career as a Catholic priest had been turbulent with departure from the Jesuit order; his involvement with Modernist writers and thinkers had led at one point to ecclesiastical censure; his 1912 biography of Ste. Jeanne de Chantal had landed on the Index of Prohibited Books. He was not a product of the prestigious Parisian Écoles normales, and he had not secured a university position. Further, the principal focus of his best-known historical work—Catholic spirituality in the seventeenth century—might easily have ensured permanent oblivion for all but a handful of readers in a secular society increasingly alienated from traditional churchly discourse.

But, just the opposite happened. Enthusiastically devouring long passages from the often obscure spiritual writers that Bremond cited in abundance, a diverse constituency had been enthralled by the liveliness and sparkle of his presentation, especially by his ability to capture the energy of the inner struggle to secure a place with God as something literary and artful, as poetry and autobiographical remembrance and journalistic intimacy and lyrical prayer. In a long tradition hearkening back at least to Saint-Simon’s famous memoirs from the time of Louis XIV, Bremond had mastered techniques of literary portraiture, of word-painting, in order to make religious affections, specifically the inner life of prayer, aesthetically compelling, not only for people who do pray, but also for those who might. And the fact that these affections were distinctively French only heightened his readership’s pride and pleasure in a wartime of desperate patriotic struggle for survival.

The occasion of his induction to the Académie thus marked a moment of extraordinary success for Henri Bremond, a moment whose peculiar significance resided in the kind of historical work that he was attempting to do and in the tenor of his “message,” as well as in the validation that membership as an académicien français entails.

Though partial imitations exist in other countries, the Académie is an institution unique to France and French society. One of the five learned “companies” that since the Revolution of 1789 and its aftermath make up the Institut de France, chartered originally by Louis XIII in 1637 with precise and strict statutes, it has a peculiar national mandate: to oversee the production of the definitive dictionary of the French language, and, second, to award prizes for distinction in the arts. The Académie functions in effect as an instrument of national unity by means of linguistic unity, with “the office not to create, but to register, words approved by the authority of the best writers and by good society.” France being a composite land of quite distinct regional dialects and traditions, with today’s multiculturalism adding to the complexity, there is in the work of the Académie the reflecting, and then reinforcing, of an aesthetically-derived social cohesion. Moreover, the work is done not by a group of professors from the universities, but by savants and successful professionals from every walk of life, including generals, diplomats and politicians, as well as artists. As the “arbiters of elegance,” the mandarins of excellence, the members of the Académie are not primarily erudite specialists, but figures representative of popular standing and general culture.

For French thinkers of every sort, moreover, election to membership in the Académie can justly be described as the ultimate and official act of recognition of one’s “voice,” of one’s popular impact, in a society where the role of the “public intellectual” remains very strong. That kind of presence of intellectuals in the public mind, whereby they constitute an “intelligentsia,” is a very European thing, an acknowledgment that ideas emanating from well-trained thinkers matter in the formation of national purpose and the setting of tone for national life. Dubbed the “Immortels” by long custom (because presumably their ideas and contributions will live on after them), and limited by statute to a membership of forty, the Académie meets regularly in closed sessions to present and discuss issues of scholarship, public interest, and cultural definition. Members are elected for life by their peers, each member occupying a specific seat in direct intellectual succession to the deceased predecessor.

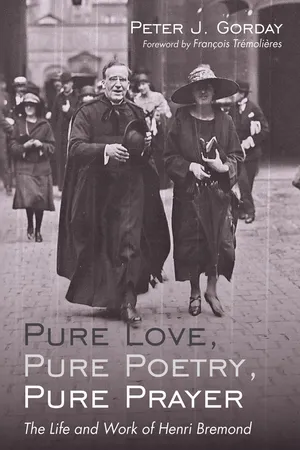

And so it is no wonder that the early afternoon of May 22, 1924, found Henri Bremond, then fifty-nine years old, both exhilarated and nervous as he prepared to complete his induction into the Académie with a substantive address. Standing on Paris’s quai Conti close by the meeting place of the Académie sous la Coupule, “under the cupola,” of the Palais de l’Institut, he greeted friends and pondered his upcoming “discours de réception.” In the traditional green-embroidered coat of an académicien for the first time, he would be officially welcomed to the podium by the Perpetual Secretary, and then begin his initiatory presentation, while new peers and specially invited guests gauged his performance. The purpose of this ritually enacted “discours” is twofold: appreciative commemoration of the work of the esteemed predecessor in the seat in question (the fauteuil), and then a sketch of the direction of the inductee’s own ongoing work. Continuity and discontinuity are in play, therefore, at the same time, a prolongation of the past and a creative anticipation of the future. Build on your forebear, but improve on him as well!

The relationship of a new member to his/her predecessor can be, thus, a subtle matter. When a sitting member dies, the first step for replacement is a formal nomination, declared by a member in writing to the Secretary of the Académie, of a suitable candidate for the vacated seat. Campaigning then begins with a round of social visits to members by the candidate in order to (gently and by implication) solicit their support, since there will have been other candidates nominated as well for the same seat, and because it is these same, presently sitting members who will cast the decisive yea or nay votes. One of the questions in the minds of the electors will be: is this candidate a suitable/worthy/sufficiently accomplished replacement for our departed and esteemed colleague?

For Bremond, the nominator was the well-known, indeed notorious for many, nationalistic novelist and propagandist Maurice Barrès, and the seat to be filled would be that of the distinguished, though massively controversial, church historian Mgr Louis Duchesne, deceased on April 21, 1922. Complications abounded. Barrès was scorned for his type of hyper-patriotic French chauvinism, including his association with the anti-Semitic, monarchist Action Française, seen by many as fascist. Duchesne was despised by many Catholics as a liberal proto-Modernist, a historical-critical debunker of saints’s legends and an irreverent, Voltaire-like wit in relation to the unspiritual foibles of church history. His landmark history of the church, critically sophisticated but deemed irreverent by traditionalists, went on the Index in 1912. With two such polarizing figures as Barrès and Duchesne to be acknowledged and honored through his candidacy, Bremond in his canvassing, and later in his induction, needed to affirm what he saw as the best in these two, while steering clear of their excesses or blind spots. It would prove to be a delicate balancing act.

What he had the cold comfort of knowing in his nervousness on that afternoon of May 22 was that, as things turned out, he had been elected by a respectable majority of votes on the s...