- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Since the rise and growth of secularization, the place of God and religion is becoming increasingly problematic in our Western culture. But what is the alternative to its Christian heritage? Humanism puts "man" at the center of everything, but can you "believe in man" just as much as you can believe in God? Is this secular worldview really rational, based on science, consistent, and durable? And above all, does our society become more humane because of it? Can you simply obliterate God from our culture and values without these collapsing like a pudding? Secular humanism has always been extremely critical of the church--and in itself that is allowed--but what if we judge and measure it with the same criteria?

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access 95 Theses on Humanism by Demaerel, Hoop in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Philosophy of Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Philosophy of Religion1

Humanism

A Bit of History

1.1 What is ‘humanism’?

1. For many people the word ‘humanism’ is synonymous with ‘humane’. Humanism however has developed itself into a veritable ideology, which, just like the religions it contests, has become an institution, a system, a power structure and can be equally militant, imperialistic, and intolerant.

This question at the beginning of this book is likely to be the most important of all. The flag of ‘humanism’ can cover, after all, very different meanings in daily language, resulting in many misunderstandings and confusion. This creates fog, smoke screens and blurred debates, whereby the same concept can sometimes be used to mean the opposite. ‘Humane’ and ‘humanistic’ have the same root but differ as much from each other as ‘social’ and ‘socialist’. A person can be very social, and at the same time distance him or herself totally from the socialist ideology and party. Sometimes ‘humanism’ is used as a synonym for ‘being humane’ (hence a moral quality), but usually it refers to a real belief system or an ideology.

In this book, we want to very strictly ‘think straight’. ‘Humanism’ comes from the Latin word humanus meaning ‘human’. The ending ‘ism’ always indicates that this one concept is regarded as a central and dominant principle (think for instance of rationalism, voluntarism, materialism, socialism . . .). In this sense, humanism is a stream of thought or philosophy of life that makes ‘man’ the highest principle. Nowadays, the term ‘humanism’ is mostly used in the sense of a non-confessional view on life meaning that everything has its starting point in man and in reason, and thereby opposes any supernatural explanation or appeal to a god. It is true that others define ‘humanism’ more broadly, as a general concept of ‘a people-oriented attitude to life’. For them, humanism can be both secular and Christian, and ‘secular humanism’ then indicates the non-confessional version. In this book, we deal more with ‘secular humanism’ for the sake of the etymological meaning (man as the highest principle). From this point of view, the expression ‘Christian humanism’ or ‘humanist Christianity’ is, in our opinion, not consistent (we explain this later in chapter 3.3). Therefore, concepts such as ‘humanism’, ‘free-thinking’, ‘secularism’ or ‘atheism’ will sometimes be used interchangeably. This can appear confusing, and ‘humanism’ can thus seem to be a container concept. In practice, however, these four words also blend together and are not strictly separated; people do mix them up in daily language. By all means, ‘man at the center of everything’, this they certainly have in common.

2. ‘Humane’ and ‘humanistic’ have the same root but differ as much from each other as ‘social’ and ‘socialist’. Every ‘-ism’ is a disproportionate extrapolation of one principle (or a part thereof). To suggest that only socialists are social is an insult to all other people, and sometimes certain socialist individuals or regimes can exhibit highly antisocial behavior.

First of all, it is helpful to explain the origin of the concept of ‘humanism’ itself. In the 14th and 16th century, this meant something totally different from the secular version of today. Let history refresh our memory and bring some clarification. In the next chapter, we want (1) to place humanism in its proper historical context, (2) appreciate it for its good intentions and accomplishments, (3) critically investigate whether its criticisms of the Church1 were correct and (4) critically research if what it replaces it with is a valid alternative, of the same value or better than what it attacks.

1.2 Humanism in the 14th and 16th century.

The oldest origin of humanism must be sought in Italy in the 1300’s. This new movement was then a purely Italian phenomenon. A number of intellectuals and artists (such as Dante, Boccaccio, Petrarca) looked with sadness at the political and cultural decline of Italy. At the same time, they exalted the illustrious past of Rome, ancient antiquity. They sought to restore pure literary Latin and introduced studia humanitatis, which means the study of litterae humaniores, comprising mainly subjects such as grammar, rhetoric, poetry, and moral philosophy. The word humanitas2 referred to the pursuit of the fine arts (especially the ancient classics), in contrast to the sacred arts, and thus was not in the least directed against God. This trend was primarily a cultural phenomenon and did not have any ideological intentions! It was esthetically inspired, and its primary interest was form, not content. In fact, the Italian humanists were pronounced Christians (also Bruni, Ficino, Pico della Mirandola). Petrarca for example began to direct himself much more toward God by the end of his life by pulling back in solitude toward prayer because he discovered that worldly literature could not give him the happiness he was looking for. From 1450 this movement also began to permeate the rest of Europe. People were tired of the strict scholastic culture with its abstract thought systems, and were attracted to the beauty of classical antiquity, which paid more attention to the beauty of men and the earth.

Although the beginning of humanism as a stream of thought is situated in the 16th century, some believe we find traces hereof with the ancient Greek sophists (a philosophy around the 5th century BC). Protagoras (± 490–420 BC) made the following statement gladly quoted by humanists, “Man is the measure of all things, of the things that are what they are, and of the things that are not what they are not.” But we need to make two side notes here. First, what Protagoras meant exactly is actually not clear, but he probably did not mean that man should be the center of the universe, but rather that a statement is only true or not true in respect to the person who says it, because he can only view it from his own perspective. He said this in the context of epistemology which emphasized the inevitable subjectivity of our judgments. Secondly, this statement was not at all targeted against religion or godliness; the ancient Greek culture was also religious to the core. This statement did not give rise to the emergence of a ‘humanist’ or atheist stream, and that was also not at all the intention.

Finally, 16th century humanism originated after the Middle Ages and had a completely different focus. It was mainly a reaction against the inhumane things that were done in the name of God: the inquisition with its bloody persecution of heretics, dissidents, witches, the intolerance, fanatical religious wars, and ruthless stakes. This response was very understandable and was also needed. It was even very Christian and inspired by the idea that a loving God would never want such things! The first humanists were invariably deeply religious people who reacted against the excesses of the Church institution and wanted to return to the original simplicity of the gospel. No one turned away from God, from the Bible, not even from the Church. The protest was directed against abuses, against the repression and dominance of the Church institution, and the lack of freedom in the area of art and science. In short, ‘humanism’ did not have the meaning in that time that it now tends to have (a secular, atheistic, sometimes anti-church view of life)3.

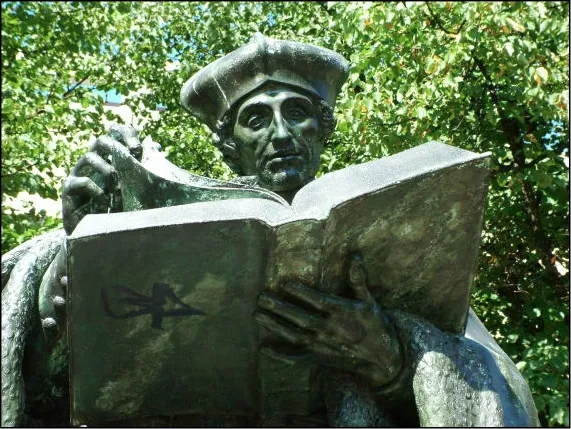

1.3 The ‘Prince of the Humanists’: Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus (1469–1536) was born in Rotterdam and became a priest in 1492. In his youth, he went to a school of the ‘Brothers of the communal life’, a kind of revival movement in the Netherlands founded by Geert Grote. This ‘Modern Devotion’ originated in the 14th century in reaction to the degeneration of church life and aspired to a practical devotion and spirituality. Later, Erasmus studied and worked in many places throughout Europe (The Netherlands, England, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, Germany . . .). He thus came in contact with all kinds of renewal movements which greatly expanded his view. He was a broad-minded and open man who could rise above the many boxes of church life at that time.

In his book ‘Praise of Folly’ (1511), with his sharp pen, he already derided the abuses and derailments of the Church in his time: the debauchery and greed of the high clergy, the abuse of power by the Church, the obstinate hunt for heretics, the dark jargon of philosophers and scholastic theologians, their bizarre subtleties and hair splitting, superstition among the people, the veneration of the saints, confession, fasting . . . His first reaction was against all the inhumanities committed in God’s name: how can the inquisition, the religious wars, the burning of heretics and witches be consistent with a God who is love? The Church was in a real crisis in his time, and Erasmus was terribly shocked by a figure like Pope Julius II who came to power by large-scale bribes and had children with various mistresses, and who was more concerned with excessive parties, war campaigns against Venice and grand buildings for which he needed mountains of money.

Another aspect that Erasmus inherited from the Renaissance and applied extensively was the saying ad fontes, ‘back to the source’. Because he had studied Greek (which was quite new at the time) he could go back to the source of the Church and Christianity, namely the Bible. Therefore, in 1516 he made a scientific edition of the New Testament from the basic language and from the most reliable manuscripts. In its preface, he describes Christianity as a wide river that was polluted by all kinds of tributaries, but if we want to know what the pure water looked like, we need to go back to the source: the words of Jesus and his apostles. Erasmus founded a school in Leuven where students, in addition to Latin, had to learn Greek and Hebrew so they could study the Bible in its original text. This also was innovative at that time and caused clashes with other professors who assumed the Catholic dogma that Latin was the holy language.

Erasmus undoubtedly launched the idea of tolerance. He disliked theological disputes and even more so, bloody quarrels because of religion. Erasmus is sometimes called a ‘biblical humanist’ because he wanted to reconcile the biblical message with a humane (men-loving) attitude. He pleaded for a tolerant and evangelical Christianity inspired by the Sermon on the Mount. Erasmus was undoubtedly a great soul, a cosmopolitan, someone who transcended his time in many ways, and in that sense, he represented many beautiful values of modern Europe. For this reason, the ‘Erasmus’ program of exchange between European universities was rightly named after him.

When, however, modern humanism refers to Erasmus as its founder, we must put this very much into perspective and place it in the right context, otherwise we run the risk of distorting history. With a retroactive effect, it is too easy to put all kinds of ideas into his mouth that he actually never had. Firstly, Erasmus never used the word ‘humanism’, not for himself nor for others (this word only emerged in the 19th century)! Secondly, Erasmus was a faithful Catholic throughout his life, moreover a priest. In no way can he be regarded as a forerunner of secular, anti-religious humanism. When some of the Italian humanists began to rave about the classics, and even began to choose this paganism, Erasmus strongly and fundamentally disapproved. He even satirized and ridiculed it as a foolish imitation that showed a complete lack of historical understanding. He also wrote in 1525, for example, that in his young years he had a strong aversion to sacred literature and preferred to read classical poetry (‘inventions of poets’...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introductory remarks

- Chapter 1: Humanism

- Chapter 2: The Humanistic Vision

- Chapter 3: Humanism in Practice

- Chapter 4: Conclusion: humanism vs. Christianity

- Previous publications by Ignace Demaerel

- Bibliography