![]()

1

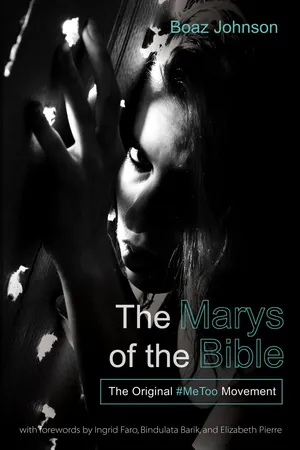

The #MeToo Movement in the Introduction to Matthew

The Genealogy of Jesus the Messiah: the thesis statement of the New Testament

The New Testament opens with the following words,

This introduction sets the groundwork for the mission of the gospel, the good news of Jesus the Messiah. On the surface, this seems like a very mundane reading of the names of all the people in the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah. It begins with Abraham and ends with Joseph, the earthly father of Jesus. It divides up the history of the Old Testament into three parts. Each part has fourteen generations (Matt 1:17). The first generation is from Abraham till the time of the beginning of the Davidic dynasty (Matt 1:2–6a). The second part is from the kingship of David till the Babylonian exile (Matt 1:6b–11). The third section is from the Babylonian exile till the birth of Jesus the Messiah (Matt 1:12–16). The basic thesis of this genealogy is that Jesus the Messiah comes to fulfill the mission and the dreams of both the Abrahamic covenant and the Davidic covenant.

What were the goals and the aspirations of these two covenants? This book will seek to address this crucial question.

While it is important to delineate the issues around the Abrahamic and Davidic covenants, the main focus of this genealogy is not on these. The main focus of the genealogy is on women. Five women are highlighted in the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah: Tamar (Matt 1:3), Rahab (Matt 1:5), Ruth (Matt 1:5), Uriah’s wife (Matt 1:6), and Mary (Matt 1:16). Each of the five women are emblematic of different kinds of evil in society. This book will delineate different aspects of these evils in society, and then set out the justice solutions which the Bible proposes.

It delineates the #MeToo voices of five emblematic women.

Each of the five women also represents a different part of the Bible. Tamar represents the patriarchal era (Gen 38); Rahab represents the Exodus era (Josh 2); Ruth represents the period of the Judges (the book of Ruth); Uriah’s wife represents the period of the kings and the prophets (2 Sam 11); and Mary represents the New Testament era (Matt 1:18–25).

Each of these eras represented different kinds of issues with which the biblical #MeToo movement needed to engage. Yet, there are also similarities and continuities underlined in the struggles of women in each of these eras.

All the begettings of the men of the #MeToo movement

The creation narrative in Genesis ends with the words, “These are the begettings of the heavens and the earth when they were created” (Gen 2:4). It is as if the heavens and earth are a couple, begetting the rest of the universe.

This word is used repeatedly in the book of Genesis, the “book of Begettings.” It is used of men begetting. It is used of women begetting. It is used of creation begetting. It is as if all of creation is given the responsibility of begetting God’s mission.

The book of Matthew, the first Gospel, also begins with begettings: “This is the book of the begettings of Jesus the Messiah, the son of David, the son of Abraham” (my translation). It is as if all the begettings of Genesis find their culmination in this final set of begettings in the Gospel of Matthew, and in the gospel of Jesus the Messiah.

Of course, it seems rather odd that creation and men also beget. In global society today, only women beget. In fact, in many parts of the world, that is the only function given to women—to beget, and to feed the babies and men. This is a very sad, global injustice against women.

In the Bible, by contrast, men are also given the responsibility of begetting. This is a huge responsibility, and were this attitude to be adopted by men, I think it would cure many of the injustices that are done against women in our modern society, injustices which are highlighted by the #MeToo movement.

In Matthew 1, the issue of Matthew’s #MeToo movement finds its place right in the middle of a string of begettings, phrases like, “Abraham begat, Isaac begat, Jacob begat,” and so on. Each of the four women mentioned in the Hebrew Bible are essentially a part of the #MeToo movement of the Bible. They are gentiles, the other. They are abused by men in power.

It seems clear to me that quite a crucial answer to the #MeToo crisis lies in a key principle seen in this “begettings genealogy.” If only men would view sex as not merely an opportunity to experience pleasure at the expense of women, but rather as an opportunity to be a part of God’s mission of begetting, there would be no sexual abuse of women.

All the Marys of the Bible

In linking Mary’s name to that of the other four women of the Old Testament in the introduction, the New Testament makes it clear that the gospel of Jesus the Messiah squarely addresses the issues of evil and injustice raised in their stories. It also links with the story of Mary and the other women in the New Testament.

Mary’s name is crucial because it is clearly a link to another crucial character in the Torah, whose name was also Mary. The texture of the book of Matthew leads us to see this clear link. The birth of Jesus in Matthew is followed by the same kind of massacre of baby boys which happened during the reign of the pharaoh of Exodus 2.

The ministry of Jesus, and particularly at the end of his life in the concluding section of Matthew, mentions several Marys who follow Jesus. Archaeological digs from the time of Jesus suggest that Mary was a very common name among the low classes of people groups called am ha-aretz. The obvious question that one may ask is, “Why is the name Mary so common during this time, and why is the name of Moses’ sister Mary?”

Several sections of the Old Testament shed some light on this. The name Mary means “bitter.” A good explanation for this may be seen in the narrative, when Naomi, . . . when Naomi, the mother-in-law of Ruth, goes back to Bethlehem from Moab, the women of Bethlehem exclaim, “That is Naomi!” Upon hearing this, she responds, “Don’t call me Naomi, the Joyful One, call me Mara, the Bitter One!” (Ruth 1:19–21)

A study of history, both during the time of Moses and during the time of Jesus, makes it clear that the Egyptians during the time of Moses, and Romans during the time of Jesus, employed the raping of girls as a tool of war and subjugation. So, little girls were called Mary, or bitter. The parents mourned when a little baby girl was born, and they said, “I am so sorry you were born a girl. Your life will be bitter, Mary.”

The Gospel of Matthew seeks to deal with issues which lead to these kinds of awful forms of injustice and evil, which all the Marys of history before the time of Jesus and during the time of Jesus endured. Women still face the same kinds of injustices and awful experiences even today.

The following chapters delineate the issues faced by Marys, then and now.

![]()

2

Tamar and the #MeToo Movement

The first instance of #MeToo highlighted in the genealogy of Jesus the Messiah is Tamar. She is a gentile Mary. The narrative of Tamar is placed in a very interesting spot in the book of Genesis. Genesis 38 is squeezed between the Joseph narrative, Genesis 37 and 39. In Genesis 37, the seventeen-year-old Joseph tells his father about the “evil” that his brothers are doing (Gen 37:2). In Hebrew, the phrase dibbah ra’ refers to systemic forms of evil, which was a part of the deep fabric of society during the patriarchal time. The next use of this word dibbah is found in Num 13:32; 14:36, 37. It refers to the nature of systemic evil that is found in Canaanite society and religion.

What is evil? The Tamar narr...