![]()

1

Introduction

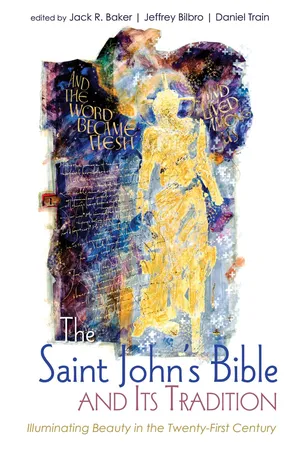

In an age of e-books and screens, it may seem rather antiquated if not downright antediluvian to create a handwritten, illuminated Bible. The Benedictine monks at Saint John’s Abbey and University, however, determined to produce such a Bible for the twenty-first century, a Bible that would use traditional methods and materials while engaging contemporary questions and concerns. Given the remarkable riches of this admittedly idiosyncratic work, this collection of essays examines how The Saint John’s Bible fits within a history of the Bible as a book, focusing especially on how its haptic and aesthetic qualities may be particularly important in a digital age marked by fragmentation and disagreement.

In an era that largely assumes the physical form of a book is a mere vessel for disseminating information, The Saint John’s Bible foregrounds the importance of a book’s tactile and visual qualities as both a response to and an aid for rightly understanding sacred Scriptures. Like their pre-modern exemplars, the creators of The Saint John’s Bible understood that the physical form of the text would itself exert a certain kind of formation in the hermeneutical and theological imaginations of its audience. For example, opening a Bible app on an iPad conditions us to practice the same reading techniques we have learned from reading other texts on screens: we tend to skim quickly, extract information, and move on when we become distracted.

In contrast, opening the pages of this handwritten, beautifully illuminated Bible fosters a different set of reading practices. As Rowan Williams, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, explains about The Saint John’s Bible, “We tend to read greedily and hastily, as we do so many other things; this beautiful text . . . offers an insight into that lost skill of patient and prayerful reading.” The remarkable, almost obsessive attention to detail, craftsmanship, and quality of materials testify to the prayerful vision behind this project, a vision that is clearly motivated by concerns other than profit and easy consumption. Indeed, as this collection seeks to show, the physical, haptic experience of reading The Saint John’s Bible is itself an invitation for readers to meditate deeply on the beauty of God’s self-revelation in his word.

For all its interest in preserving the virtually extinct craft of manuscript illumination, however, The Saint John’s Bible is emphatically not driven by a naïve nostalgia or technophobia. Rather, at the heart of the project is an abiding appreciation for the way certain modern construals of the dialogic relationship between word and image have created both an opportunity and a need for a book like The Saint John’s Bible. Like their contemporaries who live in an image-saturated, hyperlinked, and emojified culture where meaning and power are increasingly inextricable from the media in which they are embedded, the artists of this remarkable text have embraced the possibility (and responsibilities) of manifesting the Gospel’s ever-newness to an audience which recognizes that letters and words are not merely static symbols. For the team of artists and scholars behind The Saint John’s Bible, our non-linear reading practices and growing expectation that texts will be hyperlinked shares at least some affinity with the medieval practices of internalizing the Sacred texts in one’s memory so as to hear the whole of Scripture within each individual passage. As in medieval manuscript illuminations, repeated images and visual themes throughout The Saint John’s Bible provide crucial hermeneutical guides for (hyper)linking the two Testaments and reading the whole of the Scriptures at one time.

Similarly, the images in The Saint John’s Bible draw on centuries of tradition and on contemporary, technological concerns. For instance, the opening page in Matthew depicts Jesus’ family tree in the form of a Jewish menorah, a symbol that goes back to the Pentateuch; yet spiraling through the branches of the candlestick are the double-helix pattern of DNA. Jesus is the divine Messiah, and in the mystery of the incarnation he is also part of the Jewish human family. Another example can be found in the illumination of the Luke Anthology, which combines images from many of the parables and stories that are unique to Luke (see Figure 8). Donald Jackson was working on this page on September 11, 2001, and he placed the twin towers alongside the father welcoming home the prodigal son. The image suggests how the forgiveness the father practices in this story continues to guide Christians today as we seek to offer a word of reconciliation and renewal.

Moreover, in order to make this beautiful book accessible to more people, Donald Jackson directed the production of The Saint John’s Bible Heritage Edition. Creating these 299 high-quality reproductions pushed the technical capacities of modern printing. Uncoated cotton paper was needed to replicate the look and feel of vellum, but uncoated cotton absorbs ink too readily, leading to bleeding and poor color resolution. A new printing technique was used that employs ultraviolet rays to dry the ink almost immediately after it hits the paper. The gold and silver are then applied to the illuminations with a precision embosser, and many of them are hand finished. Thus no two copies of the Heritage Edition are identical, and each copy recreates the three-dimensional texture of the original manuscript.

The Saint John’s Bible, then, draws on the resources of revelation and tradition as it engages with contemporary forms, subjects, and materials in order to prompt a reawakening of the Christian tradition and imagination. Yet, it must be acknowledged, the modern technologies on which The Saint John’s Bible relies for both its imagery and its reproduction have also spawned forms of persuasion that are less prayerful, to put it mildly. The contemporary world bombards its inhabitants with slogans and ads and memes, all clamoring for attention. These forms of persuasion aim to seduce their subjects into buying particular products, manipulate them into voting for a candidate, or even terrorize them into submission; they view language and image as means of dividing, coercing, and gaining power.

But The Saint John’s Bible is emphatically not marshalling word and image in this way, either for easy, unreflective consumption or for political gain. How might we, then, distinguish aesthetic and physical forms whose beauty issues an invitation to prayer and transformation, from those forms whose aim is to manipulate and coerce? With this question in mind, the essays in this collection both draw on and aim to recover a theological account of beauty in order to better elucidate and distinguish the redemptive, prayerful power of The Saint John’s Bible. In doing so, we seek not only to restore the language of beauty within the Christian tradition, but also to offer a re-imagining and re-membering of “power” and “persuasion” as the Gospel’s proclamation of a peace that passes all understanding and promise of a transformation which makes all things new.

Embedded in the Christian tradition is a keen sense of beauty’s power to transform those whom it encounters. Whether it be the shepherds’ wonder at the angel choir’s announcement, or the disciples’ slow growth while listening to Jesus’ parables, or John’s dazed worship when encountering the glorified Son of Man, or Dante’s sanctification through studying purgatorial art, there are countless examples of the deep change that beauty can effect. Testimonies to beauty’s power are not limited to the Christian faith. The poet Rilke, while a heterodox Christian at best, famously describes art’s force in his poem “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” At the end of the poem, this ancient statue suddenly shifts from being a static object of observation and instead examines the viewer with transformative power: “for here there is no place / that does not see you. You must change your life.”

Thus, the essays in this collection draw on the rich theological resources that describe beauty’s role in divine revelation and in God’s redemption of his people. In his “Letter to Artists,” Pope Saint John Paul II describes art’s “unique capacity to take one or other facet of the [Gospel] message and translate it into colours, shapes and sounds which nourish the intuition of those who look or listen.” He goes on to articulate the way that art can make divine mystery perceptible: “In order to communicate the message entrusted to her by Christ, the Church needs art. Art must make perceptible, and as far as possible attractive, the world of the spirit, of the invisible, of God. It must therefore translate into meaningful terms that which is in itself ineffable.”

For everyone, then, believers or not, genuine works of art inspired by Scripture reflect the unfathomable mystery which engulfs and inhabits the world. The beauty of The Saint John’s Bible has moved Christians and non-Christians in the years since its completion. John Paul II speaks to this unifying quality of the beautiful when he claims that “even in situations where culture and the Church are far apart, art remains a kind of bridge to religious experience.” Art can function as a bridge because beauty uniquely is able to cross boundaries: between secular and religious, human and divine, finite and infinite. Libraries around the world have exhibited The Saint John’s Bible or purchased Heritage Editions, and its calligraphy and illuminations have caused many to see the biblical text anew. The Saint John’s Bible is a work of art that, according to Pope Saint John Paul II’s definition, has the ability to translate or, quite literally, transform the biblical text “without emptying the message itself of its transcendent value and its aura of mystery.”

As Alasdair MacIntyre argues in works such as After Virtue and Whose Justice? Which Rationality?, rational discourse becomes strained when it takes place across incommensurable traditions, and the result is the shrill public discourse we have today. Beauty offers a way forward in such a context because, as David Bentley Hart demonstrates, Christian beauty is a mode of peaceful persuasion, one that invites rather than berates, attracts rather than compels. At the end of After Virtue, MacIntyre famously calls for a new St. Benedict, someone who will live the gospel in a credible manner before a skeptical world. Perhaps The Saint John’s Bible can teach us how to answer MacIntyre’s ...