J. Zhang,*a G. B. Cellib and M. S. Brooksb

1.1 Introduction

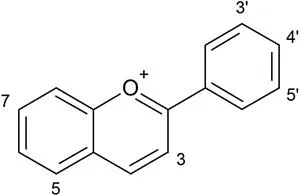

Anthocyanins are ubiquitous water-soluble pigments that have important roles in the propagation, protection, and physiology of higher plants. Evidence shows that these compounds can act by repelling herbivores and parasites,1 attracting pollinators and seed dispersers,2 and protecting plants against biotic and abiotic stresses.3 In human health, anthocyanins have been associated with various benefits due to their antioxidant,4 anti-inflammatory,5 neuroprotective,6 and anti-diabetic properties.7 Chemically, anthocyanins are polyphenols and belong to a large class of secondary metabolites known as flavonoids, with a core structure in the form of 2-phenylbenzopyrylium or flavylium cation (Figure 1.1). They are polyhydroxy and polymethoxy derivatives of this flavylium cation and can have sugar groups or acylated moieties attached at different positions.8 Although more than 700 compounds have been described in the literature,9 they are mainly derived of six anthocyanidins (aglycone form): cyanidin, delphinidin, pelargonidin, peonidin, petunidin, and malvidin.10

Figure 1.1 Core structure of anthocyanins, 2-phenylbenzopyrylium, also known as flavylium cation.

An interesting feature of anthocyanins is that they can display a great diversity of colors depending on their chemical structure and the environment in which they are found, ranging from orange to blue.11 Several factors likely contribute to the variations in anthocyanin content and profile in plants. Anthocyanin biosynthesis and structural skeleton diversity are controlled by a number of genes. As illustrated in a colored potato study, the red cultivars contained predominantly pelargonidin derivatives, while the purple/blue varieties had peonidin, petunidin, and malvidin as the main aglycones.12 A color change is usually seen in fruit over the growing and harvest seasons. For example, the intra-seasonal monitoring of total anthocyanins and specific components in blueberries showed that during the harvest season between June and August, the content had a generally increasing trend, but the percentages of delphinidin and malvidin glycosides were inversely mirrored.13 The environment also has an effect on anthocyanin production in plants. Although the specific role that these plant metabolites have in protecting against biotic and abiotic stresses is not well understood, studies have revealed interesting connections between anthocyanin profiles and various stress conditions. For example, Kovinich et al.14 reported a clear pattern of difference in model plant Arabidopsis thaliana under abiotic stresses, where low pH and phosphate deficiency induced anthocyanin accumulation, while osmotic stress with mannitol and high pH reduced the total anthocyanins level. Furthermore, some structural differences, mainly in the modification of glycoside chains, were observed under these stress conditions. In field crops, the anthocyanin content and profile are most likely affected by both genetic and environmental variations. A multi-year grape study by Ortega-Regules et al.15 showed that the total anthocyanins and fingerprint profiles varied considerably over 3 years with different weather conditions during the growing seasons for the same crop varieties, while the differences were relatively smaller for Monastrell variety grapes grown at two different locations.

Aside from their recognized health benefits, these colorful molecules from natural sources are very appealing to the food industry as colorants. The increasing interest in their use in food products has been driven by consumer and regulatory pressure to replace synthetic colorants. However, this substitution is not straightforward as anthocyanins can degrade under normal processing and storage conditions, such as during heat treatment, which would negatively impact the sensory properties of the product. Different strategies to improve the stability of these colorants have been investigated, some of which will be discussed in later chapters.

In this chapter, natural sources of anthocyanins, such as fruits, vegetables, and grains, are highlighted and discussed based largely on the literature of the past 20 years. Examples of anthocyanin-containing plants used in traditional Chinese and Indian medicine, as well as exotic plants found worldwide, are included. Mazza and Miniati8 have extensively reviewed the occurrence of anthocyanins in foods, and their work serves as the foundation for this updated account in the area.