eBook - ePub

Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond

About this book

Written by leading academics and practitioners in the field, Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond offers a detailed insight into issues and developments that shape the debate on smart villages, together with concepts, developments and policymaking initiatives including the EU Action for Smart Villages.

This book derives from the realization that the implications of the increasing depopulation of rural areas across the EU is a pending disaster. This edited collection establishes a framework for action today, which will lead to sustainable revitalization of rural areas tomorrow.

Using country-specific case studies, the chapters examine how integrated and ICT-conscious strategies and policy actions focused on wellbeing, sustainability and solidarity could provide a long-term solution in the revitalization of villages across the EU and elsewhere. Best practices pertinent to precision farming, energy diversification, tourism, entrepreneurship are discussed in detail.

As an in-depth exploration of the Smart Village on a multinational scale, this book will serve as an indispensable resource for students, researchers and policy leaders in the fields of politics, strategic management and urban and rural studies.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Smart Villages in the EU and Beyond by Anna Visvizi, Miltiadis D. Lytras, György Mudri, Anna Visvizi,Miltiadis D. Lytras,György Mudri,Miltiadis Demetrios Lytras,Miltiadis Lytras in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politik & Internationale Beziehungen & Umwelt- & Energiepolitik. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Smart Villages: Relevance, Approaches, Policymaking Implications

Introduction

Smart village may be a new, and for that matter a rather fancy, concept, yet the thrust of problems and challenges that it speaks to is by no means trivial or new. Therefore, the imperative inherent in the smart village concept and debate is to diagnose the status quo, propose viable ways of addressing problems and challenges, build consensus about the need to take action, and to actually follow the suit at micro-, mezzo-, and macro-levels. The truth is that villages – and so the romanticized picture of pastoral life and the beauty of nature, so close to childhood memories of many who will read the book – are under threat of disappearing. Several factors contribute to that. Perhaps the most important of them are progressing pace of urbanization coupled with the perceived opportunities that city life bears and negative demographic tendencies in rural areas. The problem is acute across the European Union (EU), but certainly, and regrettably so, it exists elsewhere too. As the process of depopulation of rural areas progresses, so is the heritage inherent in villages vanishing. At the same time risks, threats, and new challenges arise.

Rethinking the Rationale Behind Smart Villages: Typology of Risks, Threats, and Challenges

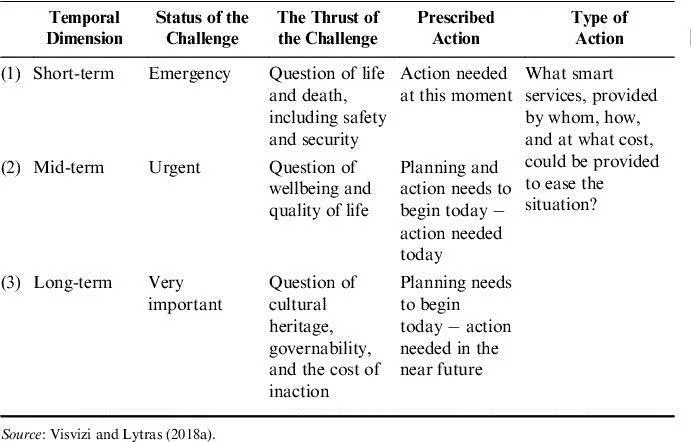

As elaborated elsewhere (Visvizi & Lytras, 2018a), depopulating villages tend to be inhabited by the elderly, usually single, in need of medical care, help with cooking, and […] just company. These people tend to be deprived of the means for living and can hardly use electronic devices, should internet and electricity be available in their village. The nature of this challenge goes beyond the question of wellbeing and quality of life. It is in fact a question of life and death. Risks to their safety include the risk of not only burglary, assault, fire, and flooding but also malnourishment and sickness. Depopulating villages frequently lack basic infrastructure, such as roads, reliable electricity grids, but also doctors, schools, and affordable groceries. This affects the wellbeing and quality of life in villages for its current inhabitants, both young and elderly. It also creates disincentives for possible newcomers and incentives for current inhabitants to leave. Depopulating villages frequently embody artifacts of inimitable cultural heritage, in terms of architecture, tradition (rites, habits), and oral history. Today’s elderly are the guardians of traditions and heritage, but who will carry our shared tradition when its today’s guardians are gone? There is also the big question of long-term implications of increasingly depopulated villages and rural areas, that is, the question of the state’s administration ability to exert its control over those areas. These are real problems that require responses. Table 1 offers a snapshot view of these problems and challenges, while at the same time hinting to the urgency of action that needs to be taken to address them.

Table 1. Smart Villages: Typology of Challenges and the Corresponding Urgency of Action.

Smart Villages: The Concept and Its Relevance

The concept of smart village made its inroad into the policymaking and academic debates nearly simultaneously. On the policymaking front, the European Commission has been the champion of ‘smart villages,’ as reflected in Cork 2.0 Declaration of 2016 (European Union, 2016). The European Parliament upheld the momentum and so the Bled Declaration of 2018 adds further content to the idea and resultant policy strategies. Certainly, the concept and the idea have been borne out of several decades of debates and policymaking pertaining to mostly Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), Regional Policy, and then Cohesion Policy. In this context, the first Cork Declaration of 1996 (ECRD, 1996) should be pointed out. Today, the concept of smart village has been defined by the European Commission as follows:

“Smart Villages are rural areas and communities which build on their existing strengths and assets as well as on developing new opportunities,” where “traditional and new networks and services are enhanced by means of digital, telecommunication technologies, innovations and the better use of knowledge” (ENRD, 2018; European Commission, 2016)

With regard to the academic debate on smart villages, the rise of interest in the concept, its application, and implications can be related to the maturing of the debate on smart cities (Visvizi & Lytras, 2018a; Visvizi, Mazzucelli, & Lytras, 2017). It can also be related to the individual discovery process, that is, field research, personal experiences, and the resulting commitment to the cause of specific researchers. Research interest triggered by the sad examples of depopulating Greek villages in Peloponnese, especially in what used to be mythical Arcadia, or the equally tragically compelling example of Epirus, proves the point.

This volume brings these two rationales underpinning ‘smart villages’ together, thus making a case for a conceptually sound, academically disciplined, empirically driven discussion on smart villages and its relevance and application in the policymaking process. Indeed, the contributing authors represent both academia and the world of policymaking, thus confirming that dialog between these two is feasible and that synergies thus created can effectively feed the policymaking process.

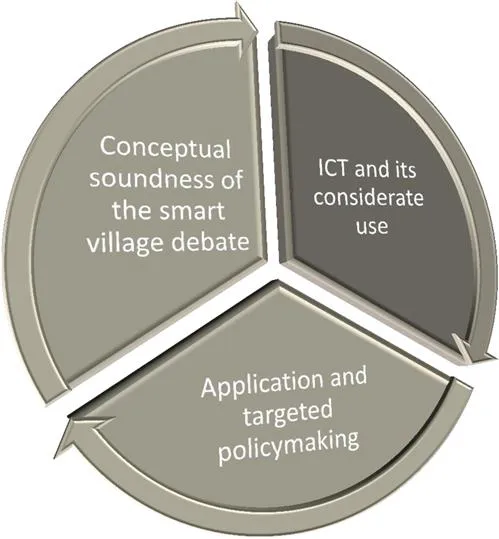

The thrust of the concept of smart village that this volume advances is therefore delineated by three issues (see Figure 1 for details). First, the focus is the village seen as an ecosystem, a microcosm, a community, and people, rather than an aggregate, largely de-personalized construct such a ‘rural area’ or ‘countryside.’ Second, the value added by modern sophisticated information and communication technology (ICT) that can be applied in the context of a village is emphasized. Considering the two points aforementioned, by ontologically reifying the village, the focus of analysis in smart village research, as outlined in this volume, shifts to inhabitants of a given village, be it plural or individual (Visvizi & Lytras, 2018a). At the same time, a considerate and ethically and socially conscious use of ICT is advocated (Lytras & Visvizi, 2018; Visvizi et al., 2017). Notably, by focusing on specific needs and challenges individuals face, and by highlighting the value added by ICT, the so-defined debate on smart villages inadvertently engages itself with diagnosis of problems at hand and prescription of what needs to be done (Visvizi & Lytras, 2018b). This serves as a bridge to the third segment of the approach that this book advances, that is, application and targeted, effective policymaking. Seen in this way, the approach to smart village that this volume promotes is comprehensive. That is, it brings together the specific to the academia conceptual zeal, highlights the value added by ICT, and engages in dialog with policymakers (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Smart Village: The Three Pillars of the Comprehensive Approach to Smart Village. Source: The authors.

Smart Villages: The Imperative The Concept Entails

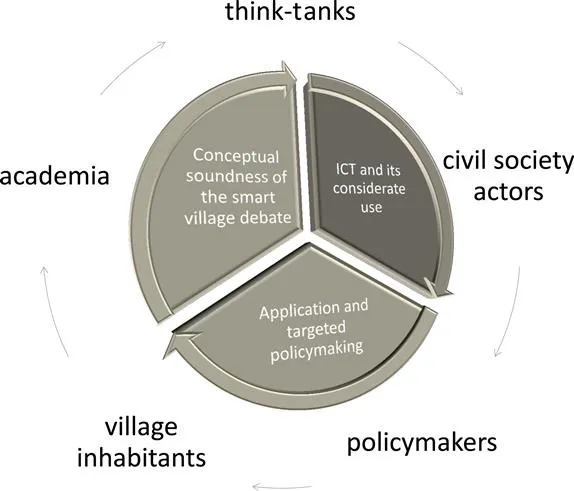

The imperative the concept and the debate on smart villages entail, to put it bluntly, is to save villages, their inhabitants, the heritage, the potential, as well as to preempt nascent risks. The challenge inherent in pursuit of this imperative is that the key stakeholders only rarely engage in a meaningful, constructive, and unbiased dialog. As Figure 2 outlines, comprehensive approach to smart villages, an approach that translates in targeted and effective policymaking, requires that all stakeholders are involved. This means that: village inhabitants are listened to and encouraged to execute their agency; the academia relates to the real problems and challenges and offers conceptually sound and methodologically disciplined frame in which these problems and challenges can be contextualized; that the think-tank sector recognizes the need to draw from academic research and engages in dialog; the civil society actors are listened to carefully; and finally, a two-way bridge exists that links these actors with policymakers.

Figure 2. Smart Villages: From Needs to Targeted and Effective Policymaking. Source: The authors.

This volume proves that dialog engaging village inhabitants, the academia, the think-tank sector, civil society, and policymakers is possible. Representing the finest universities, think-tanks, advocacy groups, and the EU institutions, the authors contributing to this volume address diverse aspects of the debate on smart villages. As a result, from the policymaking point of view, this book offers not only a compelling insight into the key issues and challenges that the debate on smart villages revolves around but also a set of recommendations as to what can be done and what actions are already underway. From an academic point of view, this book defines the emerging field of research on smart villages. Departing from the research on smart cities, cognizant of the limitations and caveats specific to the latter (Visvizi & Lytras, 2018b), the comprehensive approach to the concept of smart village, that this volume advocates (Figure 1), invites inter- and multidisciplinary research focused on real needs and challenges and committed to devising ways of navigating them. ICT is seen as one of the means of so doing. At the heart of the smart villages’ concept advocated here is the human being, inhabitant of the village, and his/her wellbeing. The chapters included in this volume skilfully draw from this conceptual and, indeed, normative framework, and convey hope that villages across the EU can be saved after all.

About This Volume and the Message It Conveys

This volume consists of 12 chapters addressing diverse issues related to the debate on smart villages. It offers a thorough insight into the concept of smart village, its application, and implications (Chapters 1, 2, and 3). The book is also filled with content drawing from developments in the field, including policymaking actions and strategies (Chapters 4, 5, and 6), issue and policy areas (Chapters 7, 8, and 9), and country case studies. Even if the focus of the volume is directed at the EU and the question of smart villages in the EU, a case is made that similar problems and challenges exist elsewhere. Chapters 10 and 11 elaborating on the cases of South Korea and the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries attest to that. Chapter 12 sheds light on the new research agenda and policymaking strategies that the smart village concept and debate necessitate.

In Chapter 2, titled ‘Integrated Approach to Sustainable EU Smart Villages Policies,’ Christiane Kirketerp de Viron and György Mudri elaborate on the origin of the smart village concept in the EU-level debate. As the authors explain, the concept of smart village emerged in EU-level policy debates on rural development in 2016, following the stakeholder-driven Cork 2.0 Declaration. It was developed through a pilot project initiative on ‘Smart, Eco, Social Villages’ and spelled out in the ‘EU Action for Smart Villages’ initiative. While the concept of smart villages remains unclear for many, substantial work has been carried out to develop the concept and to prepare the underlying supporting instruments at EU level over the last three years. The aim of this chapter is to give an overview of how the concept of smart villages has evolved at the EU level and to draw some recommendations for future policy work. The chapter reveals difficulties of the utilization efficiency of the EU funds in rural areas and shows a patched landscape of fragmented policy instruments. The key arguments are that while the mixture of these tools is important, the glue that binds them together is still missing and that the general utilization efficiency is not sufficient. The authors offer a set of five recommendations for the short to medium term, which is needed for the successful implementation of the smart approach: integration, simplification, communication, innovation, and ‘rural proofing.’

In Chapter 3, titled ‘Smart Villages Revisited: Conceptual Background and New Challenges at the Local Level,’ Oskar Wolski and Marcin Wójcik argue that the smart villages’ approach to rural development is promoted by the EU factors in the diversity of rural areas and the different nature of challenges faced by each area. The central role is assigned to local communities – formation of appropriate characteristics and attitudes that enable the creation of optimal conditions for development. This is also the result of the evolution of rural development policy, which is driven by the dynamics and direction of change of rural areas and changes in societal perception of change events in rural areas. The implementation of this development approach at the local level requires a transformation of the current school of thinking on development and the utilization of available resources. The key role in this process is played by local governments, which are part of the local community and also represent its interests. The chapter combines theoretical and practical issues and represents a geographic perspective. Its first aim is to answer the question: How can local governments create the right conditions for smart development at the local level? The second aim is to discuss the smart village approach in the context of selected development concepts. This leads to a number of specific recommendations for policymakers. It also helps them to understand the approach, which is vital in the implementation of the aforesaid recommendations.

In Chapter 4, titled ‘Toward a New Sustainable Development Model for Smart Villages,’ Raquel Pérez-delHoyo and Higinio Mora explore the question of resilience in rural areas. As the authors explain, rural communities are increasingly open to a globalized world, and migration from rural areas to cities is becoming increasingly important. Many rural areas face depopulation, an aging population, and limited access to a range of services. To address this challenge, the ICT involved in the concept of smart villages have much to offer. In order to streamline the debate, this chapter proposes a methodology based on resilience. Resilience is defined as the ability of a habitat or system to recover to its initial state when the disturbance to which it has been subjected has ceased. In this regard, a retrospective of rural areas is proposed based on the experience of the garden city model, for which the advantages of rural areas were evident over those of urban areas. The objective is to reconsider the intrinsic qualities of rural areas in order to recover and enhance them with the added value of the EU Smart Villages approach. These facets will be the driving forces behind sustainable development. In conclusion, a number of recommendations are presented, including the development of a catalog, structured by regions and territories, of rural areas and their different potentials and opportunities, for the development of smart village projects.

In Chapter 5, titled ‘The Role of LEADER in Smart Villages: An Opportunity to Reconnect with Rural Communities,’ Enrique Nieto and Pedro Brosei focus on the program LEADER (Liaison Entre Actions de Développement de l‘Économie Rurale”, i.e., ‘Links between the rural economy and development actions’), its evolution, and its value addition in the context of the debate on smart villages. The authors argue that over recent decades, rural areas have been facing significant challenges that exacerbate the existing discontent in their communities. These challenges are mostly reflected in depopulation trends, increased vulnerability to external shocks, and reduced quality of basic services. Local Action Groups (LAGs) all over Europe have been working on these challenges since the early 1990s. More recently, the smart villages concept is starting to generate enthusiasm among rural development stakeholders to try to revert these trends by supporting communities to move toward a more sustainable future while taking advantage of new, emerging opportunities. This chapter demonstrates that the LEADER approach and its principles are also part of the smart villages concept. However, practical differences between the two emerge as a result of limitations imposed by restrictive LEADER regulatory frameworks in many member states. Our main argument is that LEADER has what is needed to be the main tool for driving smart villages in Europe as long as there is a policy framework in place that enables LEADER to exploit its full potential. This conclusion is grounded on the analysis of the role that LEADER played in a number of smart villages initiatives across the EU.

In Chapter 6, Daniel Azevedo makes a powerful case for precision agriculture and its relevance for villages and their sustainability. As the author explains, stakeholders all over the EU, including academics, local and national authorities, business representatives, civil society, and the EU institutions are interested in creating a better life for citizens inhabiting rural areas. Building up on previous successful policies, including for instance the CAP and political actions, such as those outlined in the Cork 2.0 Declaration, these stakeholders assessed the current and future challenges of EU rural areas. The EU agri-food sector is not only the backbone of the EU rural areas but is also a driver of the EU economy, that is, delivering 44 million jobs in the EU and representing 3.7% of EU’s gross domestic product (GDP). The EU is thus the world’s number one exporter of agricultural and food products amounting to €138 billion in 2017. Today, the technological progress and the digital economy are transforming the EU economy in a way and speed never seen before; agriculture and food production are no exceptions. Obviously, the agriculture and the food production activities may have less obvious significance to the smart city but are key in the smart village concept. The ongoing technological transformation of agriculture will certainly enable and influence the design and implementation of any concept for smart villages. The question is therefore complex: How can agriculture and food production contribute and influence the smart villages concept and related policy strategies? This chapter dwells on this issue.

In Chapter 7, titled ‘Energy Diversification and Self-sustainable Smart Villages,’ James K. R. Watson explores the growth and opportunities of small-scale local power generation and the implication...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Chapter 1 Smart Villages: Relevance, Approaches, Policymaking Implications

- Chapter 2 Integrated Approach to Sustainable EU Smart Villages Policies

- Chapter 3 Smart Villages Revisited: Conceptual Background and New Challenges at the Local Level

- Chapter 4 Toward a New Sustainable Development Model for Smart Villages

- Chapter 5 The Role of LEADER in Smart Villages: An Opportunity to Reconnect with Rural Communities

- Chapter 6 Precision Agriculture and the Smart Village Concept

- Chapter 7 Energy Diversification and Self-sustainable Smart Villages

- Chapter 8 The Role of Smart and Medium-sized Enterprises in the Smart Villages Concept

- Chapter 9 Smart Villages in Slovenia: Examples of Good Pilot Practices

- Chapter 10 Smart Village Projects in Korea: Rural Tourism, 6th Industrialization, and Smart Farming

- Chapter 11 Smart Villages and the GCC Countries: Policies, Strategies, and Implications

- Chapter 12 Smart Villages: Mapping the Emerging Field and Setting the Course of Action

- Index