![]()

1

Introduction

People do not engage in medicinal product litigation unless they feel they have been harmed in some way. It is by definition a personal, visceral experience, and while this book focuses on the collective process, it does not in any way seek to diminish or detract from the individual experience.

This book is structured as an introduction, which briefly outlines the legal context in which litigation takes place and provides a summary of the regulation of medicines and medicinal products, including a brief history of the development of the relevant legislation, a series of 35 case studies and a chapter detailing the research conclusions.

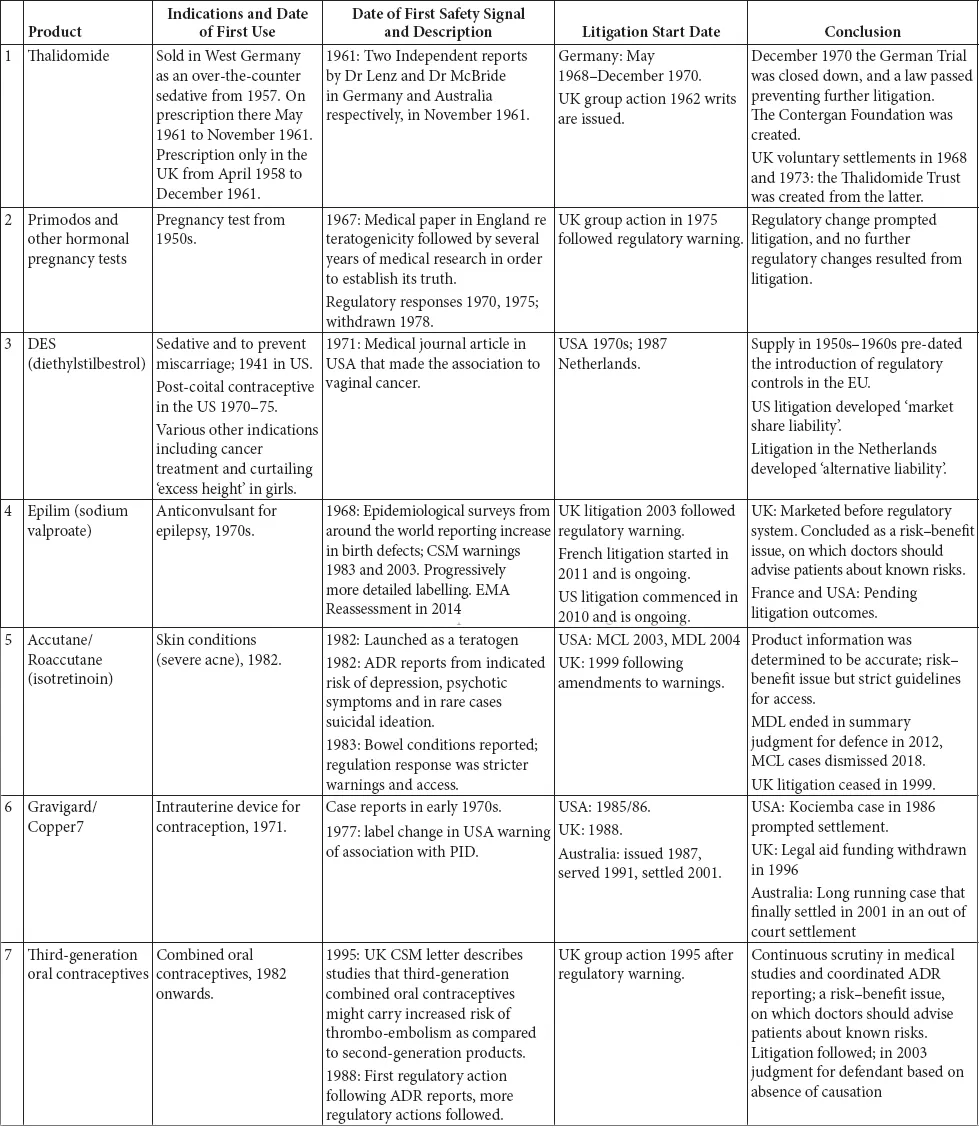

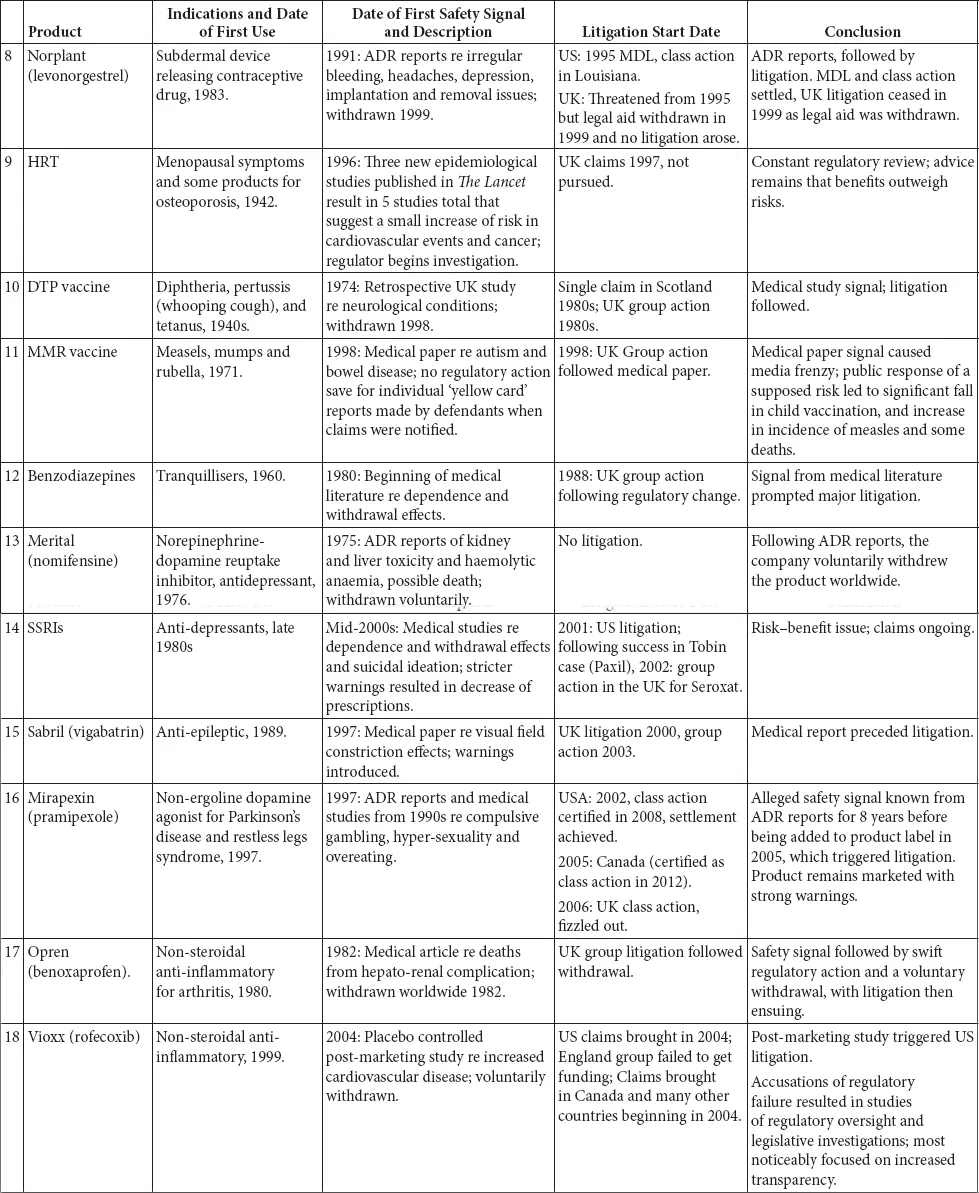

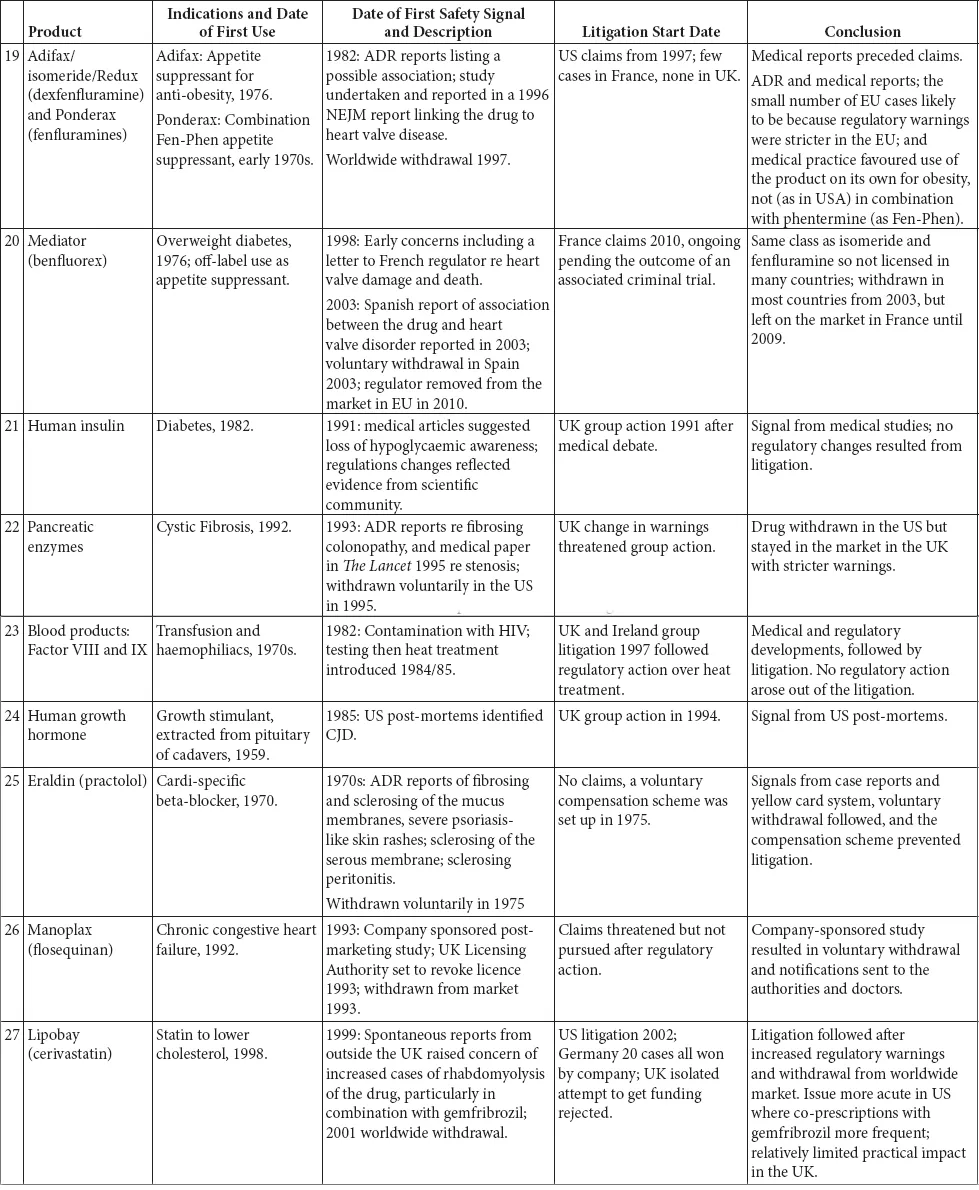

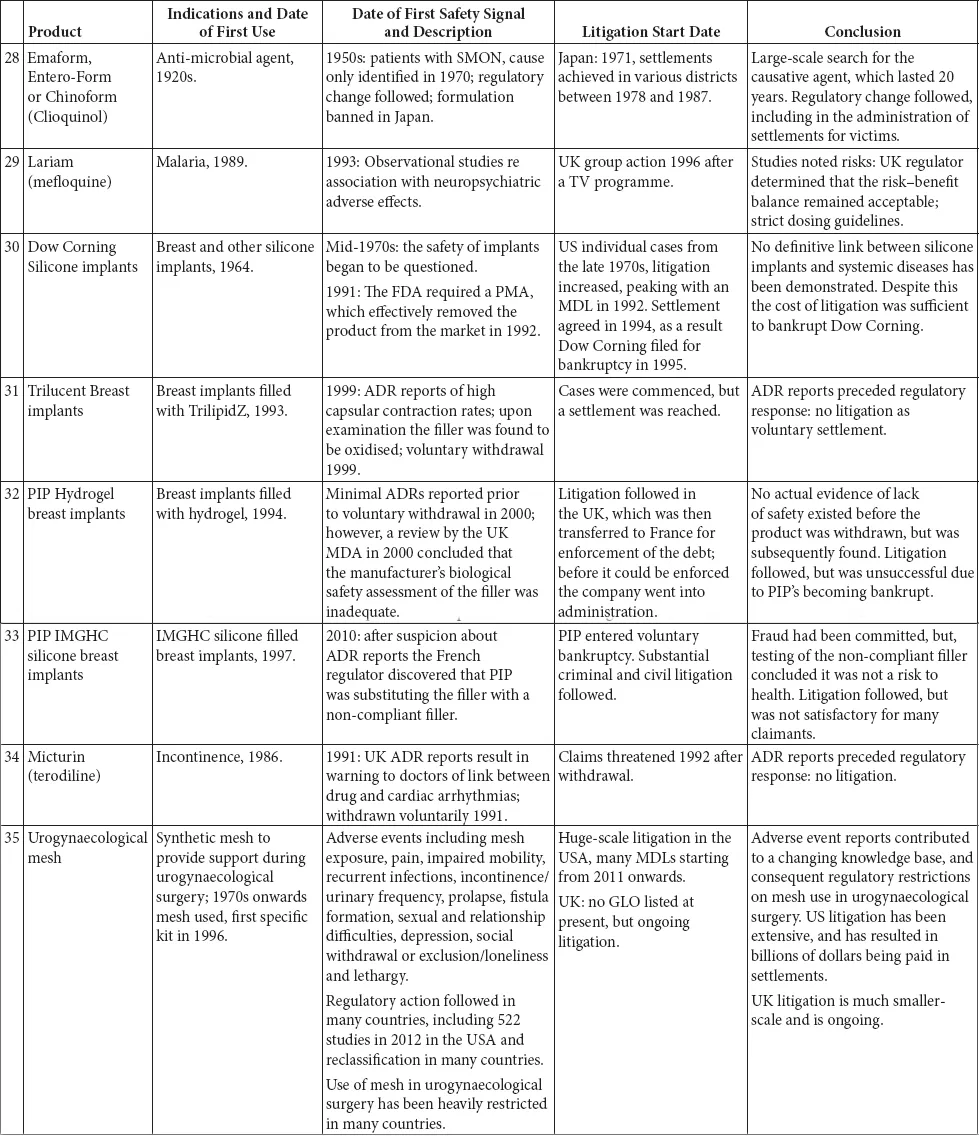

The 35 case studies illustrate the interplay between the regulatory regimes and litigation. These case studies include medicines, biologics and devices marketed from the 1940s to the present day. The case studies were selected on two bases: first, they were all the major medical product safety cases that had resulted in extensive litigation in the UK since the 1960s; and, second, they were other large cases of interest from around the world (SMON from Japan, Mediator in France, Dow Corning in the US. We do not set out to cover the very much larger corpus of medical product litigation that has occurred in the US.

The case studies are divided into broad categories, the majority of which are based on the active ingredients in the drug or the indication being treated. There is one category that is the exception to this – the first grouping, drugs known to be teratogens or thought to cause foetal damage. These drugs impact beyond their immediate recipient, so despite being different drugs for varied indications, they have been classed together. This enables an overview of how the regulation on teratogens has evolved over time, from a position where the there was no effective regulation to today’s position.

A brief summary of each of the products is set out in Table 1.1: inevitably this summary is highly selective and a fuller picture can be obtained in the case studies.

I.The Legal Context

This chapter is a short summary of the legal context within which the case studies are set, presented consciously more for non-medical or other non-legal readers in fairly simple terms. Two aspects need to be explained: the legal basis of liability, and the legal system’s procedures for processing

First, a word about legal systems. Countries have their own jurisdictions, rules and approaches. England and Wales is a unified jurisdiction, whilst Scotland and Northern Ireland have some rules that are common throughout the UK but some aspects that are distinct (such as court and civil procedure systems). The USA has some aspects that are federal and unified across the country, but also strong maintenance of individual State laws and courts.

Table 1.1 Summary of the case studies

A.Basis of Liability

Legal liability almost throughout the world is based on two main theories. The universal one is where the person who is legally considered to have caused the claimant’s harm acted negligently, that is was at fault. Under English and US law, the actions, or failure to act, of the defendant fell below a standard of reasonableness that breached a legal duty of care. These concepts of individual actors, evaluation of reasonable acting and causation can be applied to any defendant – an individual doctor or nurse, a hospital or a manufacturer. It is well known that it can be extremely complicated to investigate and examine the actions that led to harm in a medical context, and to establish whether a healthcare professional’s actions were or were not below a legal standard of reasonable care, and that a patient’s injury was caused by such a failure.

Since establishing negligence can be complicated, and hence slow and costly, a different criterion was developed in the USA and England in order to make it simpler for people to sue the manufacturers of products. This is known as ‘strict liability’, which merely refers to a liability system that is not based on either negligence or ‘absolute’ liability (since strict liability sets out some criteria and affords certain defences).

Debate in the UK on introducing strict product liability was stirred up as a result of the Thalidomide tragedy, since it was likely that the children affected would be unlikely to have been able to succeed in establishing negligence, and the same result might occur in similar cases on medicines. The Law Commission and the Scottish Law Commission led the debate on draft laws, but the new regime was not introduced until the Consumer Protection Act 1987 was passed, with rules that are harmonised throughout the EU under Directive 85/374/EC.

The EU strict liability regime requires a producer (usually a manufacturer but also an entity whose brand is on the product, and possibly a supplier) to have placed into circulation a product that is legally ‘defective’, since it does not provide the level of safety that persons generally are entitled to expect. There are various defences, and an important one for medical product manufacturers is where the state of scientific and technical knowledge at the time the product was put into circulation was not such that the defect could have been discovered (known as the ‘state of the art’ defence).1

Although the introduction of strict liability was intended to make it easier, and hence quicker and cheaper, for consumers to be able to claim compensation from manufacturers for injuries caused by products, this is rarely the outcome with medical products. This study shows problems arising in cases on causation (Vioxx, Hormonal Pregnancy Tests), market share liability (DES) and defect (MMR, valproate).

Since at least the 1960s, there has been debate over whether to shift the compensation system further, into a ‘no fault’ regime. A better description of such schemes would be ‘administrative compensation schemes’, since the structure and context are what constitute the primary changes. The inquiry moves from the adversarial context of litigation, with lawyers fighting lawyers to ‘win’, to a system in which a patient claims from an administrative body, providing basic details which are then investigated by the body with the assistance of expert medical and legal experts, to see if the criteria for payment are met.

The description ‘no fault’ is not specific, since it describes a feature of a scheme that is absent rather than present. Every system has specific criteria for triggering payment of money. The legal system uses criteria of negligence and strict product liability. Administrative schemes tend to use a list of factual medical criteria. For example, the Florida Birth-Related Neurological Injury Compensation Association2 will compensate a living child who was born weighing at least 2,000 grams either in a participating hospital or delivered by a participating physician, and who suffered injuries to the brain or spine caused by oxygen deprivation or mechanical injury during labour, delivery or during resuscitation in the immediate post-delivery period, which rendered the child permanently and substantially mentally and physically impaired. Disabilities caused by genetic or congenital abnormalities are excluded from compensation.

B.Litigation Systems

We have referred to the fact that litigation systems are adversarial. Civil procedure systems have the same basic format around the world. A claimant files a claim form and details of the claim with a court, naming the defendant(s). The defendants respond in writing. Both sides produce documentary evidence and the evidence of independent experts that support their respective positions. If the case is not settled, a public trial will be held in which the allegations and evidence, usually involving oral testimony by witnesses of fact and experts, will be set out, and a decision will be made on liability. Continental systems generally have ‘trials’ that extend over multiple successive hearings in court, whereas in the American and British common law legal systems trials will be concentrated single events, even if lasting some days or weeks.

There are major differences in procedure between the USA and UK. One is that decisions on liability and damages are made by juries in the former jurisdiction and by judges in the latter. A related difference is that levels of damages are typically far higher in USA, and it is also possible for juries to award punitive damages against defendants.3

C.Funding and Costs

Another major difference exists in how litigation is funded and how costs are charged and allocated at the end. All litigation requires intermediaries: lawyers, courts and experts. In the US, access to justice is often virtually free to claimants, as lawyers will act on a contingency fee basis, under which they are paid out of the proceeds of success. A no-win result means no fee. But a win may mean a very large fee. In a class action (see section I.D) the court, rather than one or more class members, usually awards the claimant lawyers their fee. There is no general rule that a claimant who loses will be liable to pay the defendant’s legal costs.

In England and Wales, claimants must pay their lawyers, and are subject to a ‘loser pays costs’ (cost-shifting) rule. From the 1950s until around the later 1990s, large personal injury cases could only be brought if the claimants were funded by the state, through the legal aid scheme.4 Individuals applied to the Legal Aid Board, later the Legal Services Commission, and were awarded a certificate of funding if their personal assets were below certain limits and their cases satisfied a ‘reasonable merits’ test. The system was inherently one-sided and many cases were funded that failed.5 This legal aid mechanism was orchestrated by leading claimant lawyers to fund multiparty cases, especially multiparty medicines cases. The tactical battle became one over the grant and subsequent continuation of legal aid funding.6 Over time, legal aid became unaffordable for the state,7 and was subject to successive cuts and restrictions until it was significantly reduced in 1999 (to be replaced by the unsuccessful experiment of conditional fee agreements8), virtually disappearing in 2013 for most civil cases.9

Experiments have been made with methods of payment of one’s lawyers by means of insurance policies, either ‘before the event’ (BTE) or ‘after the event’ (ATE), where the premium for latter type of policy might be very high. Such BTE legal expenses insurance policies are widely available for small individual cases in many European states, and are widely used in Germany, but appear not have been popular in UK for personal injury cases. After legal aid became unavailable, some large or multiple-claimant cases in England and Wales were funded by ATE policies.

Since 1974, experiments have been made in England and Wales with ‘qualified one way cost shifting’ rules to try to assist personal injury claimants, on the assumption that most personal injury claims were valid and defendant insurers should be encouraged to settle mo...