![]()

Part One

Relations with Materials

![]()

1

Claying: Attending to Earth’s Caring Relations

Veronica Pacini-Ketchabaw and Kelly Boucher

clay

clay cares

clay has histories

clay remembers

clay was once stone

clay experiences weathering

clay = plasticity

clay = multiple minerals

clay gifts

clay

Claying with

Clay slabs sit on Wurundjeri Country, stacked onto lino floor and plastic. Child bodies launch onto the stack. Clay is grabbed, pulled and pinched. Flat surfaces become textured with each hand pinch and fingernail scrape. Clay moves onto hands and under fingernails, onto arms, floor, knees. Clay is hard, heavy, soft. Children huff, puff and grrrr as small chunks are pulled off with pressed fingers and clenched fists. Clay bodies and child bodies wrestle and merge in a clay-child mosh pit. Clay moves into the room. Clay smears: across the floor, across plastic, onto boots. Clay is tracked over carpet. Clay travels.

Clay slabs are stacked in a line on this preschool classroom’s floor. Clay is solid, moist, sticky. Child bodies stomp across clay bodies—a clay wall leading to a tower. The stacked slabs receive boot squish and hand slap. Clay moves onto hand, knee, clothes and floor. Clay receives as bodies prod. Clay slabs are steps to climb, and clay offers child bodies extra height and a different place to stand. Ellie steps across clay and onto the castle tower. Clay is solid yet soft under booted foot. Ellie wobbles; clay supports. Clay holds her up. Clay becomes a tower, and Ellie surveys the room, delighted with her new perspective. Rita circles Ellie, shouting “Get off our tower!” Clay supports Ellie. Clay is solid, heavy, forceful, and the child-body-tower is defiant. Clay stays. Rita moves to the front of the child-body-tower and starts grabbing at the base. Clay is pulled and scooped from the bottom of the slabs. Rita digs into clay. Clay moves onto hands and under fingernails. Other children are called over to dig into the base in order to topple the tower and the child body balancing on top.

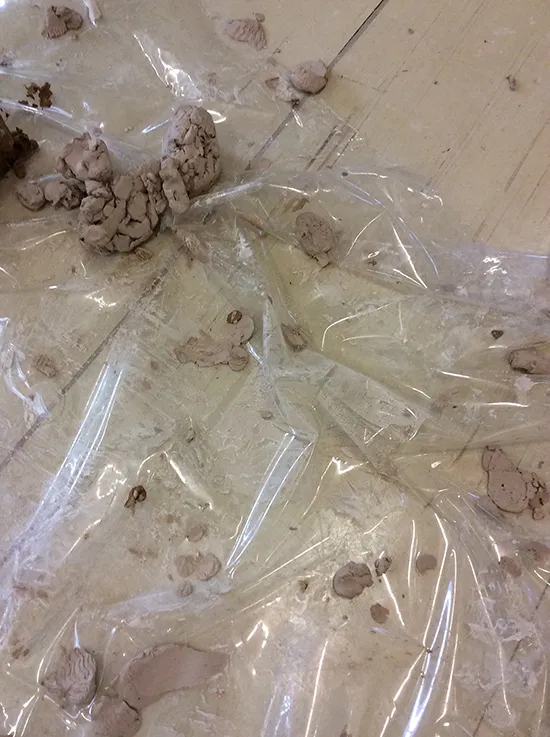

Figure 1.1 Clay-plastic movement. Photo credit: Kelly Boucher.

Wurundjeri Country receives this Wadawurrung and Dja Dja Wurrung clay. This clay is dug out of pits in Central Victoria, Australia. White clay is blended from two sites: Wadawurrung country (near the town of Bacchus Marsh) and Dja Dja Wurrung country (near the regional city of Bendigo). The terracotta clay is also Dja Dja Wurrung country (from the town of Ballarat). This clay, gathered with heavy machinery and transported in tip trucks, has traveled from a place where it was once rock. This clay, weathered and broken down over millennia, became aggregate, sediment. This clay is country, soil. This clay is living—an ecology of earth, minerals, microbes, particles. This clay might contain illite/smectites, kaolinites, smectites, micas and more.1 This clay is brought together, mixed with water and manufactured to a consistency suitable to form slabs. This clay is cut into blocks, wrapped in plastic and transported on trucks onto Wurundjeri Country, to Naam—now known as the city of Melbourne. This clay is bought from a pottery supply store and travels in the boot of Kelly’s car, then onto a trolley and into the preschool classroom. This clay is unwrapped and stacked in a line on the floor. This clay has journeyed far. Although its place of origin/country is no longer recognizable within its plastic wrap, this clay has a place. Because this clay is situated, it offers, questions and demands of children and educators to take part, to be present and to “attend and attune to questions from the world.”2 In other words, it demands that we attend to its history and memory.

Being present to/in this clay’s ecological memory enacts what Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg scholar and artist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson speaks to as an “ecology of intimacy.”3 For Simpson, this ecology of intimacy embraces and reveals land relations that are premised on connectivity, love, relationship, respect, reciprocity and freedom. As settlers in territories apart, we (Veronica and Kelly) wonder how clay might become a gift from the land rather than a natural material or even a natural resource with hundreds of uses (for instance, in education, in health, in aesthetics, in soil sciences and so on). We also ponder how clay engages as a gift that always demands modes of “clay care.”4 Drawing on María Puig de la Bellacasa’s writings on matters of care, clay care requires embracing and maintaining the multiple webs of relations already existent “in the everyday fabric of troubled worlds.”5 In other words, the challenge becomes how to care for clay that has traveled so far, been made seemingly placeless and participated in capital exchanges. How might children and educators enact modes of clay care, always foregrounded in actual clay relations, with/in pedagogies of intimacy?

Yet it is not only humans who care for clay. Clay also cares. Clay lives in ongoing relations. Clay engages in intimate pedagogies in its own rights. This, of course, does not mean that clay cares for us humans.6 We might describe this intimacy using these words of clay scientist Swapna Mukherjee: “Clay minerals can remove the ions of pollutants and contaminants from solutions,” allowing “them to play very important roles in many natural neutralising reactions and facilitate their applications in many pollution control measures.”7 For instance, clay minerals are often used for water purification and treatment,8 and clays are often used as cleaning and polishing agents.9 Alternatively, we might describe clay enacting caring through all its relations, or establishing life-sustaining connections, by drawing on feminist science studies scholars such as Puig de la Bellacasa.10 Clay cares as it “appropriates a toxic terrain” such as polluted water, “making it again capable of nurturing.”11 Clay cares when, through its multispecies communities, it does “the work of recuperating previously neglected grounds.”12 How might we attend to clay care relations when care is lived beyond human worlds?

With clay

At Komoka creek in Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee, and Leni-Lunaape territory, thousands of miles away from where child-clay bodies meet on Wurundjeri Country, we (Veronica with a group of educators and pedagogues) visit an assembly of clay aggregates. The creek, with its grayish clay floor, feeds what is now known as the North Thames River in southwestern Ontario. More than 13,000 years ago, the area where the creek and river flow was a glacier. During the height of colonial residential schools in Canada, the Komoka area was a booming railway town and fertile farming place. Now, at a time of ecological crisis, the province of Ontario has named this area a provincial park, continuing the violences of colonial practices on the territory.13

As we walk on the smooth clay floor on a warm autumn day, we feel between our toes, feet and ankles the cold, clear water running from the nearby spring. With two large plastic pails, a hiking knife and an array of small metal garden tools (one hand fork, two hand transplanters, three hand cultivators and four hand trowels), we dig into the Komoka creek clay floor. As we dig, we wonder how we might care differently for clays that do not arrive in the classroom wrapped in thick plastic bags. Might this clay remind us of its histories, of its minerals, of the war declared on the land on which we stand?14

Figure 1.2 Digging. Photo credit: Sylvia Kind.

Like the children on Wurundjeri Country, we apply force to dig out a block of iron-bearing clay that after many tries gives in to the knife’s sharp blade. Clay is rock. Carefully, we chisel the rock inside the pail as we add more and more water from the creek. Wet, cold fingers help to further disintegrate the now smallish pieces of clay. We are starting to know this clay, feel this clay, care for this clay differently. In making time for this clay’s specific temporalities, our obligations expand to the multispecies community that this clay is. This clay surface has been here for much longer than we can even imagine. This clay has been formed through relations, including the “microorganisms in microbial mats” that constantly “metabolize and use materials from the surrounding air, water, sediments, and rocks.”15 Drawing on Puig de la Bellacasa’s writings,16 by “focusing on the temporal experiences” of Komoka clay, we are beginning to disrupt current conceptions of clay that are depleted from the clay’s own minerals and lively entanglements.

We pour water into the pail to regenerate the fine chunks of clay. Fatima Andrade and colleagues explain that

when water is added to dry clay, the first effect is an increase in cohesion, which tends to reach a maximum when water has nearly displaced all air from the pores between the particles …. Addition of water into the pores induces the formation of a fairly high yield-strength body.17

As “water acts as a lubricant,” we begin to make sense of clay’s plasticity.18 Clay scientists define plasticity in clay mineral systems as “the property of a material which allows it to be repeatedly deformed without rupture when acted upon by a force sufficient to cause deformation and which allows it to retain its shape after the applied force has been removed.”19 In fact, it is clay’s plasticity that allows the child bodies on Wurundjeri Country and our bodies on Anishinaabe, Haudenosaunee and Leni-Lunaape land to convert clay “into a given shape.”20

Several shapes emerge from the regenerated clay: Balls that we throw and catch between us as we stand on the creek bed. Nests that mimic the nests that a group of young children had made the day before our visit to the creek.21 Other shapes that are not necessarily identifiable. Big shapes. Tiny shapes. Shapes that stand strong on tree branches. Shapes that crack and disappear.

We gift these shapes back to the creek and the river.

Figure 1.3 Assembling. Photo credit: Sylvia Kind.

Objects travel through the gesture of gifting. Public Share,22 a collective of artists from Aotearoa, focuses on the notion of sharing and exchange via the everydayness of clay and the production of clay vessels, containers and objects. For example, as a response to the politics of urban development, a group of artists collected clay from Auckland’s SH16 northwestern motorway construction site in Te Atatu, New Zealand, and used the sourced raw clay...