![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE EMBASSY, THE AMBASSADOR AND THE POLITICAL ENVIRONMENT

It must be accepted that policy will be increasingly decided in Washington. To proceed as if it can be made in London and ‘put over’ in Washington, or as if British policy can in the main develop independently and can be only ‘coordinated’ with American, is merely to kick against the pricks. Policy will thus be increasingly Washington made policy. But it need not therefore be American. It may be Anglo-American.1

One of the outcomes of World War II was an irrevocable shift in power to Washington. This shift in the making of policy towards Washington, together with Britain’s post-war aspirations in the field of Anglo-American relations, inevitably escalated the importance of the British embassy. This chapter considers the structure of the embassy, the ambassadors who led the embassy during the period under review and the political environment in which they operated. Before considering these issues, however, it is appropriate to consider briefly where the embassy fitted into the machinery of the Foreign Office and therefore of the British government, and the role diplomacy played in the making of foreign policy.

The Foreign Service came into being in 1943 and was the result of the amalgamation of the Foreign Office and Diplomatic Service with the Commercial Diplomatic and the Consular Services.2 This new Crown service was the means by which official relations between Britain and other sovereign states were conducted.3 The minister responsible to Parliament for the Foreign Service and the conduct of foreign affairs was the Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, a position held by Ernest Bevin from 1945 to 1951. The headquarters of this new service was the Foreign Office. The head of the Foreign Office and the Foreign Service was the Permanent Under-Secretary. This position was held by Sir Alexander Cadogan from 1938 to 1946 and by Sir Orme Sargent from 1946 to 1949.4

The Foreign Office was divided into 35 departments.5 The most important of these, from the Washington embassy’s point of view, were the North American Department and the newly formed Economic Relations Department. The Superintending Under-Secretary of the North American Department from 1945 to 1947 was Sir Neville Butler; he was replaced by Sir Michael Wright in 1948.6 Both had spent time at the embassy in Washington; Butler served from 1939 to 1941 and Wright served with Lord Halifax until 1946. The Superintending Under-Secretary of the Economic Relations Department until 1947 was Sir Edmond Hall-Patch, who had moved from the Treasury in 1944 and had laid the foundations for the Foreign Office’s growing economic work. He was one of the principal economic advisers to Ernest Bevin and played a significant role in both the Financial Agreement negotiations, being one of the team sent to Washington in September 1945, and in the British response to the Marshall Plan. He was succeeded as Superintending Under-Secretary by Roger Makins (discussed more fully below) who returned from Washington in 1947.

The role of these departments was twofold: firstly to collect and analyse information received from the overseas missions, e.g. the Washington embassy, with a view to assisting the Foreign Secretary in the formulation of policy proposals, and secondly to assist in the execution of policy by drafting instructions for use by the overseas representatives.7 The purported function of the embassy, then, in relation to the Foreign Office was (and still is) to collect information and pass it on, and to receive instructions and act upon them. This two-way flow formed the basis of the essential relationship between the Foreign Office and the embassy.8 The detailed structure of the embassy is considered below.

During the war, a ‘mini Whitehall’ was established in Washington with virtually every government department having an establishment in the city. In addition to this mini Whitehall, a variety of new missions and other British agencies were established. These included the Supply Mission, the Shipping Mission and the embassy Relief and War Supplies Department. Combined Boards with the Americans and later the Canadians were also formed; these included the Combined Production and Resources Board (CPRB), the Combined Raw Materials Board (CRMB) and the Combined Food Board (CFB), The result of this was that ‘the official British presence in Washington swelled to a peak of 9000’.9 These various bodies were, however, formed mainly for the purpose of waging war. The majority of them were closed down shortly after the war ended, some became dormant and yet others metamorphosed into international bodies. The CPRB and the CRMB, both formed in 1942, were, in accordance with America’s aspirations for free trade, closed down in December 1945.10 The CFB, after consultation with 19 other countries, turned itself into the International Emergency Food Council in recognition of the world’s continuing food shortages.11 The missions were also largely dissipated; some were shut down while others had their functions or a part of them transferred to the embassy. One of the largest missions, the Supply Council, was closed down in March 1946.

Although the British presence in Washington during the war was exceptional, the benefit of close collaboration with the Americans during the war had not been overlooked. As Hall Patch noted in 1945:

Through our war time machinery we receive from Washington a mass of most valuable material of high quality covering a very wide field, and we are able to make our views known. . . among the innumerable US agencies.12

Britain wanted to retain access to this high-quality material and to continue making its views known across the US Administration. One method of achieving this, at least in part, was to retain the establishment that the embassy had developed into during the war and indeed expand it. In 1938, the total staff at the embassy in Washington amounted to 52 people; by August 1946, shortly after Inverchapel took over, the figure had grown to over 400.13 The embassy was to continue growing. This change in numbers from the pre-war level to the post-war level is a vivid demonstration of the change in Britain’s policy towards America over that period.

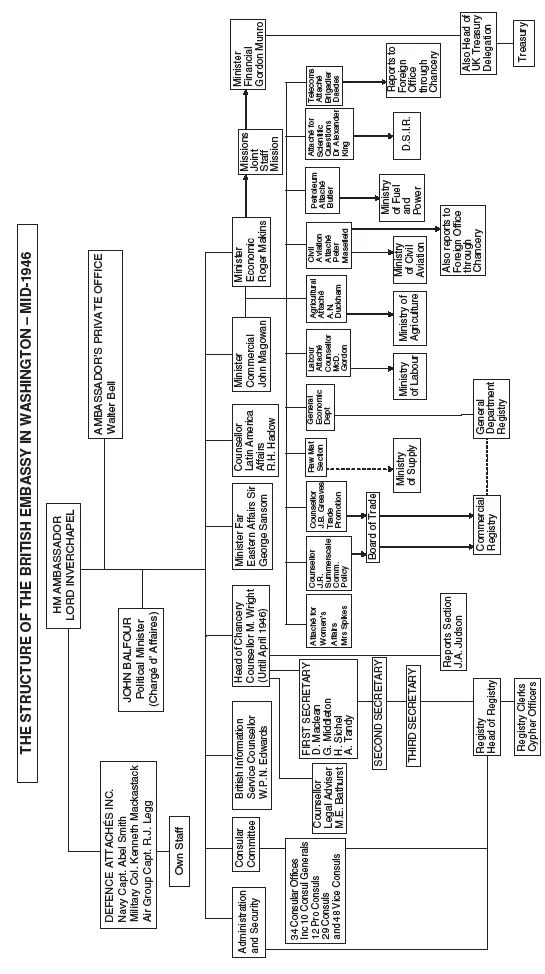

Chart I is a reconstruction of what the Washington embassy looked like in mid-1946.14 Attempting to draw a picture of the embassy is rather like drawing a landscape; one is faced with an ever-changing scene. This is particularly so in the period 1945 to 1948 when the embassy was adjusting to the post-war world. Nevertheless it is believed that the image presented as at mid-1946 is representative of what the embassy looked like in the period. It also has the merit of coinciding with the time Lord Inverchapel took over from Lord Halifax and it contains most of the key players in the period under review. The work of the embassy might perhaps be divided into five parts: Chancery, including administration, registry and reports; Economic and Commercial, including the relevant attachés; British Information Service (BIS) covering publicity and communications; the Consular section and finally the Defence attachés.

In considering Chart I, it is worth noting the titles for respective persons. Although it may be obvious, the seniority ranged downwards from ambassador, through to Minister, Counsellor, First Secretary, Second Secretary and finally to Third Secretary. An indication of the relative status of these positions might be gleaned from their remuneration. Inverchapel received a salary of £3,500 with a frais de représentation (the term given to allowances received by the heads of missions) of £16,000. Sir John Balfour (minister) received £2,500 plus a frais de représentation of £2,500, and Roger Makins (minister) received a salary of £2,000 and an allowance of £2,000. The following salaries were received by certain Counsellors: William Edwards £1,700, Michael Wright £1,300, H.A. Greaves £1,200. The First Secretaries might receive between £600 and £900 and Second Secretaries around £450. The Counsellors and Secretaries would also have received allowances commensurate with their status and duties.15

Aside from the ambassadors, who are discussed below, the most senior person serving at the embassy between 1945 and 1948 was Sir John Balfour. After Eton, Oxford and internment during World War I, Balfour joined the Foreign and Diplomatic Service in 1919. Between 1924 and 1928 he served with the embassy in Washington, initially as a Second Secretary and then as a First Secretary. It was to be the first of three postings to America. In 1940, after postings in Sofia, Budapest and Belgrade, he returned to the Foreign Office to head the American Department. It was a posting where he learnt something, in part from Lord Lothian, of the American mood and of its propensity to veer towards isolationism. In 1943, after a spell in Lisbon, he moved to the British embassy in Moscow where he worked for, and developed a close relationship with Inverchapel, or Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, as he was then known. Along with Averell Harriman, the American ambassador in Moscow, Balfour was one of the early converts to the view that the Soviets would be a source of agitation and conflict in the post-war world. In April 1945 Balfour moved to the Washington embassy as the number two under Lord Halifax. In Washington, he frequently had occasion to act as the Chargé d’Affaires, a role he had sometimes fulfilled in Moscow.16 Balfour remained in Washington until the summer of 1948. It will be seen in subsequent chapters that Balfour’s ability, evidenced in his political reports, to combine his perception of the American mood with his views of Soviet behaviour in the post-war world was both perceptive and accurate. After the stint at Washington, Balfour became the ambassador to Argentina. He remained there for three years before ending his mainstream diplomatic career as the ambassador to Spain. In 1955 Balfour had one final stint in America when he became a UK delegate to the United Nations.17 It can be difficult to discern why a diplomat is moved from one posting to another. It is possible that Balfour was moved to Washington in 1945 because of his knowledge of Russia and his experience in Eastern Europe. This was, perhaps, an early indication that the Foreign Office understood the importance of the Russian card in Anglo-American relations. By the time Bevin was established in the Foreign Office this thinking was certainly influential. Writing to Halifax regarding Inverchapel’s appointment Bevin wrote: ‘I felt it was important for the future to have someone in Washington who had a good knowledge of Russia and the East as well as Europe.’18

The ambassadors’ private office was headed by their respective private secretaries, who included Jack Lockhart for Halifax and Walter Bell for Inverchapel. The private office was important not just for the smooth running of social events and the organisation of the ambassadors’ entertaining, but also because it was an ‘efficient unit for seeing that he [the ambassador] is equipped . . . to put over his own personality and the British case to the “great American public”’. The private secretary played a significant role in the preparation of the ambassadors’ speeches.19

The core of the Washington embassy’s work was the consideration of political questions and this work was centred in Chancery. Chancery consisted of unspecialised members of staff who dealt with political issues and ‘[were] thus in a sense the backbone of the mission’.20 Although members of Chancery were not specialists in the sense that, for example, Commercial Counsellors were, they did tend to have their own areas of specialisation within the political work. A.H. Tandy, for example, covered the Near and Middle East, Jewish and Zionist affairs; D. Maclean looked after Civil Affairs, Reparations and Western Europe; and G.H. Middleton specialised in Soviet and Eastern bloc affairs, among other things.21 Chancery was also responsible for advising the ambassador on any legal matters that arose out of negotiations between America and Britain.22

Paul Gore-Booth, who worked in Chancery in 1945 and was its acting head for a period of time, described the head of Chancery in an embassy like Washington as a ‘kind of universal joint between all sections of embassy activity and to a considerable extent between those sections and the head of the Mission. ..the good functioning of the embassy machine depends greatly on the performance of this universal joint’.23 The head of Chancery in 1946 was Michael Wright who, as previously mentioned, went on to become the head of the North American Department at the Foreign Office and later was to hold the ambassadorships of both Norway and Iraq. Gore-Booth, too, was destined for high office. He was the ambassador to Burma and High Commissioner in India prior to becoming the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office. The specialisation within Chancery enabled the diplomats to establish relations with their counterparts in the State Department, thus cementing a closer relationship between the embassy and the American Administration.

The Reports Division of the embassy was responsible for the Weekly, Quarterly and Annual Political reports produced primarily for the benefit of the Foreign Office, although they were also circulated to certain ministers. Their objective was to report trends in public opinion and changes in the opinion of the establishment, particularly when these changes might affect Anglo-American relations. During most of the war, the division was headed by Isaiah Berlin.24 Although these reports usually went out in the name of the ambassador or the Chargé d’Affaires, they were usually written by members of this department and were edited, where necessary, by the head of Chancery. In addition to the regular political reports, the division was also responsible for more ad hoc reports, such as one entitled ‘American comment on the British loan and the course of the Congressional hearings and debates on the subject’.25 These particular reports on the loan were, in fact, drafted by a less famous member of this division, J.A. Judson.

Judson was also the embassy’s liaison officer with Congress. Michael Wright had the idea in 1946 for the embassy to have a full-time Congressional specialist. The objective was to strengthen the relationship between Congress and the embassy by increasing and focusing upon Congressional liaison. An example of this was a series of ‘stag parties’ organised by the embassy with the ambassador and/or John B...