- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Shortlisted for the Millia Davenport Publication Award

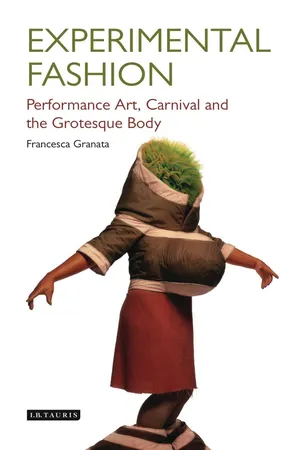

Experimental Fashion traces the proliferation of the grotesque and carnivalesque within contemporary fashion and the close relation between fashion and performance art, from Lady Gaga's raw meat dress to Leigh Bowery's performance style. The book examines the designers and performance artists at the turn of the twenty-first century whose work challenges established codes of what represents the fashionable body. These innovative people, the book argues, make their challenges through dynamic strategies of parody, humour and inversion. It explores the experimental work of modern designers such as Georgina Godley, Bernhard Willhelm, Rei Kawakubo and fashion designer, performance artist, and club figure Leigh Bowery. It also discusses the increased centrality of experimental fashion through the pop phenomenon, Lady Gaga.

Experimental Fashion traces the proliferation of the grotesque and carnivalesque within contemporary fashion and the close relation between fashion and performance art, from Lady Gaga's raw meat dress to Leigh Bowery's performance style. The book examines the designers and performance artists at the turn of the twenty-first century whose work challenges established codes of what represents the fashionable body. These innovative people, the book argues, make their challenges through dynamic strategies of parody, humour and inversion. It explores the experimental work of modern designers such as Georgina Godley, Bernhard Willhelm, Rei Kawakubo and fashion designer, performance artist, and club figure Leigh Bowery. It also discusses the increased centrality of experimental fashion through the pop phenomenon, Lady Gaga.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Experimental Fashion by Francesca Granata in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Against Power Dressing

Georgina Godley

The 1980s saw an aesthetic emerge in Western fashion in which a recuperation of past styles cobbled together into a pastiche came to the fore, and with it came a silhouette which, although partially quoting earlier periods, particularly the 1940s and 1950s, altered the female body in novel ways. This recuperation of sartorial styles from earlier decades, albeit not limited to this period, could be argued to have reached a certain frenzy in 1980s fashion in particular, and late twentieth-century fashion more generally.1

The female fashionable body that is most closely associated with the 1980s, particularly within women’s work wear across Europe and North America, was characterised by exaggerated overly padded shoulders matched by oversized clothes. This coexisted with the bodycon look, characterised by form-fitting garments and in part developed in response to the growing focus on health and fitness, but also more simply as a result of technical improvements in stretch materials. Women’s work wear in the 1980s was epitomised by the so-called ‘power suit’, which, through its attendant rhetoric about the importance of self-presentation in the increasingly corporatised work environment of the 1980s, has since become inextricably tied to the rise of the enterprising self and the neoliberal politics of Margaret Thatcher-era Britain and Ronald Reagan-era United States.2 It was immortalised by the1988 Mike Nichols film Working Girl (Fig. 1). The film recounted the way in which Melanie Griffith’s character is able to scale the career ladder specifically by undergoing the kind of sartorial engineering widely promoted by the popular literature and visual culture of the period, and perhaps most successfully by the John T. Molloy dress manual The Woman’s Dress for Success Book.3

Fig. 1Publicity shot from Working Girl, 1988, ©20thCentFox/courtesy Everett Collection

The power suit, which soon became a work uniform in its own right, was an obvious approximation of men’s career wear, one which seemed specifically based on the ideal fit male body of the 1980, while retaining a level of ‘appropriate’ femininity by being, in most cases, a skirt suit. This somewhat literal imitation of male dress as a requirement of entry in certain positions of power is of course problematic, as it falls within an understanding of women as an imperfect version of men. The shortcomings and false progressiveness of 1980s power dressing and its attendant feminine ideals are further highlighted by the fact that it persisted alongside a wholesome and traditional version of femininity which is best encapsulated in the period’s fashion reference to the 1950s. Significantly, the decade staged various returns to the 1950s through its popular culture as well, perhaps most explicitly in the Robert Zemeckis’s film Back to the Future (1985).

While 1980s fashion created a masculine broad-shouldered silhouette, the so-called ‘fashion avant-garde’ and figures who operated at the margin of fashion appeared to be subverting this silhouette, both within the same decade and, perhaps more overtly, in the next. Among the designers who explored new shapes and ideals of female bodies in the twentieth century are some of the most seminal figures of the 1980s, and to some extent 1990s, fashion: the Japanese Paris-based designer Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons, the British designer Georgina Godley and the British designer, artist and club figure Leigh Bowery. In keeping with the 1980s, Kawakubo, Godley and Bowery resorted to excessive padding and oversized clothes, yet they subverted these signs and produced a silhouette that is antithetical to the mainstream 1980s silhouette and to the history of fashion more generally. They produced, instead, a pregnant body shape. In spite of their different positions and relations to the fashion markets, all three created a silhouette implying the maternal body, which had been palpably avoided by fashion design in the twentieth century.

Vivienne Westwood also challenged the fashionable silhouette of the period through her use of non-fashion models and by reclaiming undergarments from prior centuries, such as the bustle, the cage crinoline and the pannier, to create a silhouette that accentuated parts of the bodies, particularly the hips and the buttocks, which were generally ‘contained’ by twentieth-century high fashion. She never, however, created what could be construed as a pregnant silhouette, perhaps as a result of her work’s indebtedness to Western fashion in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a period that did not accentuate an oversized abdomen but, rather, its opposite. Thus, even though Westwood’s work is often in line with the grotesque canon, she does not take on the reproductive female body and its attendant pregnant body shape as a number of designers of this period do, which is the focus of the first part of this book.4

The maternal body appears in utmost contrast with the high fashion silhouette of the greater part of the past century. The twentieth-century fashion body remains one of the most articulate attempts at the creation of a ‘perfect’ and perfectly contained body restrained and sealed, which greatly contrasts with the pregnant one. The reason for this exclusion can be attributed to the long and entrenched history in Western thought of assigning negative connotations to the generative female body and reading the maternal as threatening and grotesque, and can be ultimately read as evidence of a pervasive gynophobia within twentieth-century Western fashion. (I use the term gynophobia, as opposed to the more commonly used term misogyny, because it more aptly describes the fear of the maternal, the prefix ‘gyno’ from the Greek gyne, woman, being often associated in the English language with female reproduction. It is also a more pliable term. It has been theorised as allowing for a greater agency on the part of women, and as implying a fear of femininity and of the maternal, which can be experienced regardless of gender or sexual orientation.)5

The maternal and the grotesque

Tracing the fear of the pregnant body within the history of Western thought goes well beyond the scope of this work. However, it is important to note how this revulsion towards the generative body shaped the history of the grotesque across disciplines, and how it has been read as one of the principal reasons why the grotesque has been marginalised within the Western aesthetic canon.6 Alternatively, it can be argued that the maternal body has been, in great part, excluded from the Western representational tradition as a result of its association with the grotesque canon.7 As Mary Russo points out in her book The Female Grotesque, references to the pregnant body are somewhat implicit in the term’s etymology. “The word itself [...] evokes the cave” – the grotto-esque … As a bodily metaphor, the grotesque cave tends to look like (and in the most gross metaphorical sense be identified with) the cavernous anatomical female body.’8

The relation between the pregnant body and the grotesque was perhaps most clearly articulated during the Enlightenment, particularly within the arguments on the nature of conception. A number of Enlightenment thinkers attempted to purify and dematerialise birth processes by aligning them with creation and the mind, which, according to the Cartesian model, was inextricably male. That this realignment could never be fully completed was used to explain the persistence of the grotesque: ‘Natural imperfections and corporeal defects were caused when that fleeting spark mixed with matter (which, according to eighteenth century thought was inextricably female), giving rise to distortions, passions, and disease.’9 And since ultimately ‘nature was permitted to take the substance for the reproduction of man only from his mother … [this] became the source of many accidents’.10

Gynophobic discourses surrounding birth processes and the maternal body, particularly as articulated within medical discourses in the West, have, however, persisted into the present. A thorough discussion of the way the birth process and the maternal body have been pathologised in the medical discourse, particularly in their relation to dirt, can be found in Exploring the Dirty Side of Women’s Health.11 Employing Mary Douglas’s definition of dirt as ‘matter out of place’ representing a dangerous mixing of categories,12 the book explores the ways in which the maternal body and birth processes are categorised in the medical establishment and placed at the bottom of hierarchies of power due to their association with dirt: ‘The pregnant woman is a paradigm case of boundary transgression as well as the forbidding mixing of kinds’, a condition which, explains the pathologisation of birth processes.13 The current fascination with the pregnant bodies of celebrities underscores its relation to the abject, as opposed to reading as an acceptance of pregnancy, by substituting a relation of revulsion to one of almost morbid attraction. It is also important to note how part of the interest in the bodies of pregnant celebrities consists in their sudden return to a ‘normal’ and fit pre-pregnant body. It is dependent on representing pregnancy as a fashion to be worn, as the perfect bump becomes a commodified object of fashion through celebrity culture and the media, as opposed to an embodied experience.14

It is partially in opposition to Enlightenment thought that Bakhtin reclaims the grotesque, the attributes of which he celebrates as a much- needed corrective to ‘abstract rationalism’, which could not accommodate ‘the contradictory, perpetually becoming and unfinished being’.15 And if one understands the grotesque in Bakhtinian terms, its references to the maternal become particularly explicit. According to Bakhtin’s theories, the grotesque is a phenomenon of reversal, of unsettling ruptures of borders, in particular bodily borders. The grotesque body is an open, unfinished one that is never sealed or fully contained, but it is always in the process of becoming and engendering another body. He writes in Rabelais and his World that the grotesque body ‘is a body in the act of becoming … it is continually built, created, and builds and creates another body’. In contrast, the twentieth-century fashion body conforms to Bakhtin’s notion of the classical body of official culture:

a strictly completed, finished product. Furthermore, it was isolated, alone, fenced off from all other bodies. All signs of its unfinished character, of its growth and proliferation were eliminated; its protuberances and offshoots were removed, its convexities (signs of new sprouts and buds) smoothed out, its apertures closed. The ever unfinished nature of the body was hidden, kept secret; conception, pregnancy, childbirth, death throes, were almost never shown. The age represented was as far removed from the mother’s womb as from the grave … The accent was placed on the completed, self-sufficient individuality of the given body … It is quite obvious that from the point of view of these canons [meaning the classical canons] the body of grotesque realism was hideous and formless. It did not fit the framework of the ‘aesthetics of the beautiful’ as conceived by the Renaissance.16

Confirming Bakhtin’s assessment, Kenneth Clark, in his seminal – albeit by now controversial – study on the history of the nude, places the phenomena of growth and what appear to be pregnant enlarged female bellies in the so-called alternative convention. These were conventions of bodily representation alternative to the principles of symmetry and harmony characteristic of the classical model. Clark traces the origin of the alternative conventions to the northern Gothic, but regards it as having survived into twentieth-century painting and sculpture through artists such as Paul Cézanne and Georges Rouault. Significantly, he also traces an analogy between the alternative convention and the non-Western cultures of India and Mexico, which unsurprisingly he does not place in any kind of chronology. Unlike Ba...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Information

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 Against Power Dressing: Georgina Godley

- 2 Fashioning the Maternal Body: Rei Kawakubo

- 3 Performing Pregnancy: Leigh Bowery

- 4 Deconstruction and the Grotesque: Martin Margiela

- 5 Carnivalised Time: Martin Margiela

- 6 Carnival Iconography: Bernhard Willhelm

- 7 The Proliferation of the Grotesque: Lady Gaga

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography