![]()

~ 1 ~

Introduction: Terminology and Disciplines

Considerable confusion exists in the discussion of traditional buildings and it seems wise at the outset to establish the limits of terms and definitions in order to avoid further confusion. The word traditional refers both to procedures and material objects that have become accepted as a norm in a society, and whose elements are passed on from generation to generation, usually orally, or more rarely by documents that have codified orally transmitted knowledge, instructions, and procedures. This is not to imply that traditional processes and objects do not change over time (Figure 1-1). They often do, but usually slowly enough that their provenance is clearly seen or easily established. Though change is a constant in any society, it is the rate at which a society is forced to absorb the new that determines whether it can retain its integrity (Carver 1981, 27).

In traditional societies,

people have to make do with whatever is at hand. The form and arrangement of dwellings, for example, are constrained by the availability of local materials, the nature of the local climate and the socioeconomic facts of life. To a modern observer, the material world thus created can have enormous appeal because everything in it has a purpose, and because its aesthetic qualities emerge unobtrusively out of the serious business of living. (Tuan 1989, 28).

The concept of “traditional dwelling,” normally employed to describe a simple structure, often can be quite a complex conception. In warm environments where so much of daily life is lived in the open, the concept of a house as a structure is not as important as that of the entire compound, “the idea of a bit of land which is screened for privacy and which contains some enclosed internal space, and some outside space. This whole thing taken together is thought of as the home environment. Each part within is used as seems most appropriate in the circumstances” (Rodger 1974, 105). Such a view is common throughout many traditional societies in areas of warmer temperature, and is especially strong where individuals live in extended family groups, or even clans (Thompson 1983, 204). The concept is further clarified by Alison Shaw’s (1988, 54) observation that “in Pakistan ownership of land is more important than ownership of a house.”

The cooler climate equivalent of this extended concept of the dwelling is the notion of the farmstead, with all its buildings and facilities, as the unit of residence, rather than the emphasis being placed on just the dwelling. These expanded concepts of the traditional dwelling will reappear throughout subsequent chapters.

“Tangible evidence of the past found in extant architecture enhances the present by providing a time perspective and by creating through contrast and harmony a feeling of location or situation. Furthermore, a sense of continuity and permanence conveyed by surviving material culture provides psychological security” (Robinson 1981, xviii). Also, some secondary elements may change, but at the same time others do not, thus verifying the traditional nature of the object or procedure (Figure 1-2). “By its relative immutability the dwelling offers a sustaining sense of security against the uncertainties of a milieu in which change is inevitable, but directions are imperfectly perceived and mechanisms are poorly understood” (Steward 1965, 28).

One of many such examples that could be cited is what happened with the log cabins built early on by the Scots-Irish in eastern North America (Evans 1965, 34). In Ireland, the Scots-Irish had built partly excavated sod huts, or much less often, stone huts, but in North America they rapidly shifted to the widespread construction of log houses. However, in the process they retained the floor-plan dimensions of the old-country huts (Figure 1-3), which made it easier and more acceptable culturally for them to use the new material (Noble 1984, 1:44). Certainly, other factors also played their part: the abundance of timber, the easier construction with logs versus stone, and the successful example of the neighboring Germans, Finns, and Swedes, who came to North America with long traditions of log building.

Fred Kniffen (1960, 22) reported a similar traditional tenacity from Louisiana, asserting “that the form of a structure persists even when the materials change.” The hand of tradition is a strong one. Still another aspect of cultural tenacity has been reported by Ake Campbell (1935, 68), who noted the continuing custom in Ireland of “having farm-animals housed under the family-roof.” He further observed, “this custom cannot be ascribed to poverty as it is still commonly met with among people who, if they so desired, could easily afford separate accommodation for the domestic animals. They prefer, however, to cling tenaciously to the old custom.”

One term that, thankfully, is less and less often encountered is primitive architecture or primitive building. These words are frequently used in a way that implies negatively the “intention or mental equipment of the builder.” Properly, the term describes only the cultural and technical development of a society (Brodrick 1954, 100). Even when used correctly, the terms are vague (Raglan 1964, 3–4), and reflect negatively upon structures, that are often precisely designed, symbolically executed, and more carefully fitted to the local environment than so-called “professionally” planned structures. “Too often we view the products of a past pioneer technology as primitive and crude when they are in fact quite complex and exacting” (Welsch 1967, 335). Too often “the notion of the ‘primitive hut’ is commonly introduced as a hazy stereotype in many standard works of architectural history, as the supposed link with ‘the cave’ in the lineal ascent towards today’s cityscape” (Duly 1979, 5).

In discussing traditional buildings one encounters other terms that appear from a hasty glance to have a somewhat similar meaning. Folk building or folk architecture is usually employed to describe practices or structures which are the products of persons not professionally trained in building arts, but who produce structures or follow techniques which basically have been accepted by a society as the correct or “best” way.

Speaking of the folk builder, Alan Gowans (1966, 10) says that he

builds not so much functionally as adaptably – that is, not so much consciously thinking out solutions to particular problems of light, air or circulation (like a modern architect), as embodying in his work inherited generations of experience and with adjustments to local climate, materials, and social customs. . . . If the folk builder expresses his building materials frankly, it is not from any conscious convictions about architectural honesty or the virtues of handicraft (he will not hesitate for example, to cover stone walls with plaster or whitewash if that will protect them from frost).

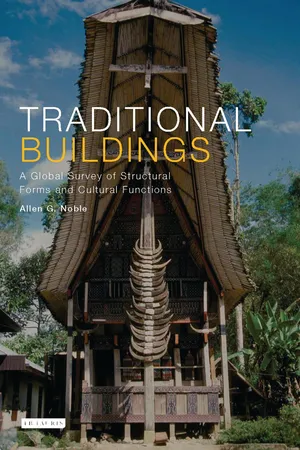

One author, perhaps with unconsciously clever wit, has characterized folk architecture as “the architecture of habit” (Gamble 1990, 23). Even an outsider, after limited exposure, can recognize some buildings as belonging to a particular ethnic group. Just how strong this connection is, and how significant is folk architecture, has been emphasized by Peter Just (1984, 30), who – speaking of Indonesia – noted that “traditionally, each of the scores of Indonesian ethnic groups had a distinctive architectural standard for every house built by a member of the group, which constituted an active expression of that group’s ethnic identity. The design of a house often had deep symbolic resonance for its inhabitants.” Speaking of a different people in a different place, geographer Peirce Lewis (1975, 2) labels “common houses as cultural spoor,” thereby emphasizing the house to be a cultural identifier.

Although folk houses are rarely identical to one another, they follow conventions accepted by their society and passed down orally. An unconscious recognition of this fact has been recorded by Sylvia Grider (1975, 51), who quoted a shotgun house carpenter as saying that such houses, for which no blueprints or drawings were ever used, “were always built by ear.” Individualized expression is of limited value in folk building, but the overall similarity is symbolic of identification with the group that resides within them (Oliver 1977, 12).

Again, the example of the Scots-Irish in North America differentiates them from both the Germans and the Finns. The Scots-Irish log house is immediately identifiable as different from that of the Germans or the Finns or any other ethnic group (Noble 1984, 1:41–5, 121–2). The Scots-Irish utilized a rectangular, one- or two-room plan, typically with one door and one window, gable hearth and chimney, and horizontal logs or boards above the plate-log level in the gable. The Germans employed a three-room, less rectangular floor plan, a massive, centered, interior-positioned hearth and chimney, and vertical boards enclosing the gable (Brumbaugh 1933; Bucher 1962) (Figure 1-3). The Finns built log houses with extremely tightly fitted logs, which to a large extent eliminated the need for the considerable chinking required by the other groups. Corner notching used by the Finns also was usually more complex (Figure 1-4).

Among the earliest scholars to recognize the cultural significance of traditional buildings, as expressed in folk architecture, are those folk-lorists who were exponents of the folk-life approach. Together with cultural anthropologists, they studied, in the words of Gwyn Meirion-Jones (1982, 3) referring to British folklore scholars, “not only the fabric of the building, its materials, construction and plan, as well as the archaeological and architectural evidence of change, but also the folkways of those who inhabited it, their customs, superstitions, habits of work and play, their music, literature and oral traditions.”

Vernacular architecture is a term widely used in the United Kingdom, and less so in North America (Ennals and Holdsworth 1998, 241f). Paul Oliver (1969, 10–11) reminds us that the term was employed as long ago as 1858. The expression was widely used and popularized by archeologists “to describe buildings that are built according to local custom to meet the personal requirements of the individuals for whom they are intended” (Carson 1974, 185). Its differentiation from the designation “formal architecture” is emphasized by Michael Karni and Robert Levin (1972, 92): “the study of vernacular architecture is not the study of intellectualized styles and modes as they are manifested in grand buildings. Rather, it is the study of how skilled craftsmen have met the building needs of their group by using the materials available to them.”

In a more expanded discussion, the eminent Irish cultural geographer F.H.A. Aalen (1973, 27) expands the definition and its application by noting,

Within regions there is marked and voluntary adherence by the majority of society to a single model or ideal pattern of house form. Even though professional builders may be operating, the basic model is not seriously questioned by builder or peasant. The model has no designer but is part of the anonymous folk tradition and tends to be persistent in time. Conformity, anonymity, and continuity may be seen as the hallmarks of regional vernacular architecture, reflecting the cultural coherence, simplicity, and conservatism of present communities and the deep rooted traditions within the building craft.

Geographer Martha Henderson (1992, 15) offers the observation that “vernacular architecture is an historical and geographical record of a culture group’s relationship to physical and social environment.” Gwyn Meirion-Jones (1982, 166) further suggests that vernacular architecture is an outgrowth and refinement of very early building, which is labeled “primitive.” The author further wrote, “there can be no clear divide between the ‘primitive’ and the ‘vernacular’ in architecture. The one merges into the other as skill improves and the tradesman, be he carpenter or mason, is increasingly brought into the construction process.”

In its most precise usage the term refers to types of structures that occur in a limited area. The usage was borrowed from linguists who used the term “vernacular” to refer to language limited to a particular region (Haase 1992, 11). Thus, words, phrases or grammatical constructions in English found only in Cornwall, for example, comprise the Cornwall vernacular language (i.e. its version of the more widely spoken standard English language).

When it is said that someone is speaking their “vernacular tongue,” it is widely understood that the person is speaking a language indigenous to his or her area of upbringing. It is not normally a term which many people might associate with a style of architecture. At the same time, however, a vernacular building and a vernacular language share many characteristics. Both belong to a recognizable tradition that has evolved over many generations and both have features that are particular to the locality in which they are found. (Dublin Heritage Group 1993, 4)

Building skills also “resemble language to the extent that they are taught by demonstration and learned by imitation so that the idiosyncrasies of teachers are passed on to pupils, thereby consolidated in a generation or two and perpetuated in the long term” (Mason 1973, 15). Jay Edwards (1993, 18) has observed,

traditions of American vernacular architecture, and low-level polite traditions which function like them, are formulated principally from the perspective of shared geometric regularities rather from that of stylistic attributes. Such traditions are implicitly recognized and understood by their designers, and are identified by their users primarily in terms of consistent geometric forms and spaces and the conventional relationships which obtain between them. Other aspects of a vernacular tradition remain variable and even expendable.

One of the distinctive characteristics of vernacular architecture study is its interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary focus. “Vernacular architecture has been examined from the perspectives of art and architectural history, social history, folklore, anthropology, historical and cultural geography, archaeology, architectural theory, and sociology to name only those disciplines that come immediately to mind” (Upton 1983, 263).

The initi...