![]()

1

DREAMS OF IVAN’S CHILDHOOD

The production history of Ivan’s Childhood (Ivanovo detstvo, 1962), Tarkovsky’s debut feature film, is a story of drudgery and labour in vain, but with a triumphant ending. The Mosfilm studio initially commissioned Eduard Abalov to adapt a novella by Vladimir Bogomolov for the screen, but then stopped the production due to the unsatisfactory quality of the rushes. A year later, in June 1961, a new artistic team was appointed, with Andrei Tarkovsky as its director. The script, which was based on a typical Soviet war-hero text, subsequently underwent drastic changes and the previously filmed material was discarded in its entirety. The resurrected film features key elements of Tarkovsky’s aesthetics and launches his intricate cinematic journey in space and time. In spite of being rooted in the socialist-realist tradition, however, Ivan’s Childhood transcends the rigid boundaries of the genre. The film still traces the fate of Ivan: it shows how the wandering child becomes a war hero by joining reconnaissance troops and providing crucial information for the Soviet army at the cost of his life, but the heroic war narrative is transformed into a drama of lost childhood. Ivan’s military achievements are overshadowed by his castaway, orphaned condition – the boy is stripped of heroism and glory.

This transformation in some way explains why Abalov’s film project and the novella, both succinctly titled Ivan (a simple personal name), became the film Ivan’s Childhood (the noun ‘childhood’ paired with the possessive adjective of ‘Ivan’ in the original Russian). The chronotope of childhood is non-existent in the text, while it shapes the cinematic adaptation. A vision of real and at the same time abstract childhood, not the figure of Ivan with his military exploits, is the sole concern of the film. First lieutenant Galtsev, the conventional first-person narrator of the text, gives way to Ivan – the visionary narrator within the film. The child-protagonist, however, does not direct or oversee the progression of events – there are no internal monologues or off-screen commentaries: he is merely a seer who longs for his childhood.

The difference between the literary precursor (the novella Ivan) and the cinematic successor is striking, and already manifests itself in the way the two works begin their narratives. ‘I intended to check the battle outposts that night, and, giving orders to wake me at 4.00, I turned in a little after eight’1 is the straightforward and somewhat uninspiring opening sentence of Bogomolov’s novella. It announces the military setting and provides precise and factual information. The writer, who himself joined the Soviet army in his teens and served in military intelligence, offers competent knowledge of warfare, and the reader gets a sense of what lies ahead from the very first sentence – a tragic but life-affirming heroic narrative, which unambiguously presents the heroism of the Soviet people in their struggle against the ruthless enemy. More importantly, the novella begins with the pronoun ‘I’ – a definite grammatical construction. The reader is not yet aware who this ‘I’ is, but its presence is already established. The beginning of the film, on the other hand, is characteristically Tarkovskian – it disorientates the viewer from the very start. Ivan’s Childhood begins with a dream, while the dreaming subject is not yet introduced. The socialist-realist artefact is transformed into a product of ‘socialist surrealism’.2

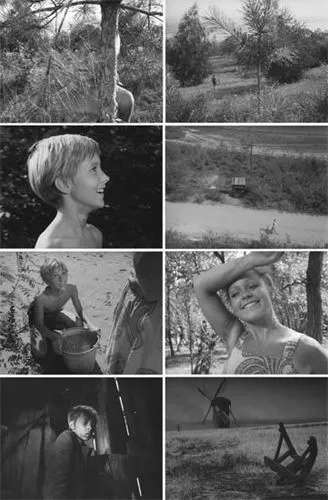

The very first shot shows Ivan, curious and carefree, looking through an improbably massive spider’s web. The boy listens attentively to a cuckoo, as if observing the Russian belief that the bird can predict how many more years a person will live. His face seems to be an image of innocent, happy childhood, but his countdown to death has indeed already begun. The boy then explores the peaceful Central Russian landscape until he encounters a butterfly. The image of the flying insect is followed by Ivan’s own flight – a crane shot lifts him right off the ground. The implausible elevation of the hero signals that the filmic reality encountered by the viewer has an improbable character. A rejoicing Ivan is raised above the surrounding trees and then gradually approaches the land as if sliding down a hill. The lightness of the flight is consequently balanced by the heaviness of gravity; the boy carefully observes tree roots interweaving in the clay earth. A cuckoo is once again heard, and the sound is followed by Ivan’s encounter with his mother, who carries a bucket of water, maternal milk, from which Ivan drinks. Air, earth and water – three out of four natural elements – manifest themselves in full glory. The fourth – fire – comes in the form of sudden machine-gun fire, which kills the mother (Figure 1.1). This dense journey from a state of utter happiness to one of devastation and loss is interrupted, and the boy wakes up; the transformation is accompanied by music, which, unlike the music or soundscape of Tarkovsky’s subsequent films, transparently cues the viewer’s emotions.

Pavel Florensky’s dictum that ‘art is materialized dream’3 seems to have caught the director’s attention, since he wrote down the saying in his diary.4 The category of dream as an alternative reality is essential to Tarkovsky’s aesthetic strategy and manifests itself in his very first film. The oneiric qualities of Ivan’s Childhood are difficult to overlook. The cinematic journey, which is supposed to depict the cruel realities of warfare, begins with an unreal event: the dream. This antagonistic interplay between alternative realities, such as dream-hallucination and ‘real’ reality, is at the core of the film’s overall compositional strategy. Indeed, the director claims that he clearly saw the structure of the film when he conceived the idea of dreams and ‘extraordinary effects involved in dreams, memories and fantasies’.5 The dreams punctuate the film’s narrative, and the protagonist is the dreaming subject, who differs from everyone else and who is probably on the brink of experiencing something which Eugenio Montale calls ‘the constant contempt of those who think reality / is what one sees’:6 for his father-figures and mentors fail to recognize his inability to distinguish between the real and the imaginary.

The boy is traumatized by the brutality of warfare. He confronts the past by re-experiencing the most memorable scenes and events of his life. It appears that the trauma manifests itself in a Freudian manner – through dreams based on certain memories of childhood. Indeed, the classic phenomenology of dreams posits that nightmares allow the brain to learn how to gain control over emotions resulting from distressing experiences. To seek meaning in dreams is a natural human impulse, and this epistemological quest is expected to deliver therapeutic effects. But Ivan’s dreams are neither curative nor redemptive; they do not provide either guidance or divine inspiration. Instead, they tend to disorientate both the protagonist and the viewer. The dreams challenge the representational order of ordinary experience. They constitute repetitive patterns, which enclose the character and distort his perception of reality.

Jean-Paul Sartre, in an open letter to Mario Alicata, the editor of L’Unità, fiercely defended Ivan’s Childhood from attacks in the Italian press. The philosopher illuminates the conceptual kernel of the film when he states that Ivan’s condition is a drama of the inability to differentiate between the imaginary domain of hallucination and the cruel reality of the war:

We continue to see Ivan from the outside, just as in the ‘realistic’ scenes; the truth is that the whole world is a hallucination for this child, and that this very child, monster and martyr, is in this universe a hallucination for the others. This is why the first sequence cleverly introduces us to the true and false world of a child of the war, in describing everything from the child’s actual flight through the woods to the false death of his mother . . . Madness? Reality? Both: in war, all soldiers are mad; this monstrous child is an objective witness to their madness because he is the maddest one of all.7

A state where a hallucination confronts or experiences another hallucination is the aesthetic condition of the film. The displaced boy finds himself in a spatio-temporal labyrinth where one is unable to make distinctions between inside and outside, war and peace, dream and reality, or madness and reason. Sartre continues: ‘for this child gravitating toward suicide, there is no difference between day and night. In any case, he does not live among us. Actions and hallucinations are in close correspondence.’8 Ivan’s place of dwelling is somewhere else – it is real and unreal at the same time.

To some extent, Sartre replicates Arthur Schopenhauer’s argument about dreaming, which Tarkovsky quotes in his own diary. The German philosopher’s line of reasoning is delivered through the prism of time: ‘The fact that time flows the same way in all heads proves more conclusively than anything else that we are all dreaming the same dream; more than that: all who dream that dream are one and the same being.’9 Schopenhauer also deconstructs the overbearing presence of the singular plane of reality and undermines the safe distance and stable boundary between the observer and the observed – they both merge into one dreaming entity. The latter point is literally realized towards the end of the film, when Galtsev appears to be dreaming Ivan’s dream: the act of dreaming is accomplished posthumously by another person, when the boy, the original dreaming subject, is dead.

The cinematographic apparatus is an almost perfect means for a director if he or she attempts to create an artistic universe with unstable boundaries between dream and reality, for the screen knows only one homogenous plane – a flow of images at twenty-four frames per second. Moreover, cinema in general can be perceived as a duplicate of the real plane and at the same time as an equivalent of dream. On the one hand it records real or staged events, which indeed have taken place, and on the other, as several critics have pointed out, the cinematic experience in a dark theatre is comparable to the process of dreaming. Tarkovsky’s film inhabits this liminal dream–reality zone, and thus fully exploits the key features of the cinematic apparatus: Ivan, other characters and the viewers all experience the unreality of the real, and they all dream dreams.

However, since the protagonist’s nightmares are not mere manifestations of the unconscious domain, the dream–reality binary is not a fully satisfactory conceptual framework for Ivan’s Childhood. One could consider Ivan’s illusionary experiences, since they indeed represent a visually distinct spatio-temporal plane, to be akin to a ‘vision quest’ as practised by Native American tribes. A vision quest takes place before puberty and constitutes a turning-point in life, for its purpose is to find spiritual and secular guidance. A child sets off on a personal spiritual quest alone in the wilderness for several days, usually goes through a delirious experience, and acquires the spiritual knowledge necessary for adulthood. Ivan, who is no longer a child but has not yet reached adulthood, sets off on his vision quest into the wilderness of the other bank of the Dniester-Styx, but ultimately fails to reach his goal. He never returns.

Oneiric Waters

But before the final ill-fated quest to the land of the dead is accomplished, Ivan enters the domain of Morpheus several times. After capturing the boy on the front line, a sentry guard escorts him to Galtsev’s quarters, where he challenges the authority of the commanding officer. The misapprehension is resolved and Ivan is given paper and a pencil to record his secret information, and then offered a washtub with hot water. Water transfigures the boy; he emerges as a blond, pale, skinny youngster. He listlessly takes a couple of spoonfuls of gruel, and then falls asleep on the table, exhausted. Water again emerges in the foreground: the sound of dripping water starts haunting the scene, and Ivan begins dreaming of a well.

Though a drastic temporal change is imposed (a vision of the real or distorted past), no spatial cut is introduced in the sequence. A close-up of burning logs is followed by a shot of an iron bowl collecting dripping water and Ivan’s arm hanging over the side of the bed. Water, which is apparently falling from a hole in the roof, drips over the boy’s hand. The two antipathetic elements – water and fire – share the same space in this scene. This antagonistic fusion constitutes a conceptual move which signifies a transition from the real to the visionary realm; it frames the dream sequence: the episode begins with the image of water and its opposite, fire (burning logs and dripping water), and concludes with the same combination (a gunshot combined with splashes of water). After the close-up of the wet hand, the camera tracks aside and unexpectedly reveals that Ivan’s bed is placed inside a deep well.

The transition from Galtsev’s hut to the well, accompanied by eerie music, is startling. The two incompatible places are joined together into a single spatial extension. What is crucial here is the fact that the continuous temporal stretch is not disrupted either; there is no montage-cut and the sweeping-tracking camera ensures temporal continuity. This momentary cinematic trick, which lasts for about two or three seconds, has immense aesthetic consequences. The temporal transition (from the present to Ivan’s past experience) is accomplished through space. Space and time intersect and form a complex spatio-temporal web. Tarkovsky refines this artistic device throughout his career, and perfects it in later works such as Mirror, Nostalghia and Sacrifice.

The spatial incongruity, the confluence of the hut and the bottom of the well, is followed by the fallacy of spatial-bodily ‘identity’ when the camera ‘looks up’, for it catches a glimpse of a second Ivan, who drops a feather down the well. The singularity of the protagonist is undermined: Ivan is sleeping at the bottom of the well and at the same time peeking inside from above. The boy’s identity splits and the paths of his two alter egos converge in a single space, the well. It is striking that dissociative identity disorder, a medical condition, includes symptoms that seem to be manifest in Ivan: distortion or loss of subjective time, auditory hallucinations, and recurrent flashbacks of abuse or trauma. The viewer is tempted to psychoanalyse Ivan, for his dreams seem to be an open book even for an amateur psychoanalyst. However, Ivan’s dreams exceed the grief–happiness binary pair; the oneiric visions constitute a more subtle interplay.

A rather sentimental conversation is taking place at the top of the well. The mother tells her son that even on a bright sunlit day one can see stars at the bottom of a very deep well. Ivan is puzzled: how is it possible to see a star during daytime? ‘For you it is day, for the star it is night’, is the answer he receives. Day and night, black and white, illusion and reality once again intermingle in the film. The explanation, though apparently improbable and scientifically false, excites the boy; he reaches down and tries to catch the light beneath the surface of water. The virtuoso camera shot, as if from beneath water, is followed by another split-identity image: Ivan is again inside the well trying to catch the star – the same feeble and glimmering light, but this time the image is accompanied by ominous German voices. The well in this sequence functions as a mirror, and it fails to distinguish between the real plane (Ivan) and the virtual plane (his reflection). Tarkovsky uses the well’s rectangular shape as a framing device, and water is a natural reflecting surface. Ivan merges with his own reflection-double and enters another domain. But unlike Alice he does not enter Wonderland; his province is a ruinous Wasteland: Soviet Russia at the height of the Second World War.

The interplay between the top and bottom levels, accomplished by means of close-ups and distant shots, leads to a dramatic culmination: life and death, another binary pair, make their way on to the cinematic screen. The mother lifts the bucket up (a life-affirming gesture) but, once a sudden gunshot is heard, it plunges back down the well and hits the water’s surface (an image of death). Water splashes out over the murdered woman, and once again the boy returns to his dying mother. In the first two dreams there is no gradual transition between waking and sleeping, and instead the director introduces hard cuts, accompanied by sharp sounds such as screams or gunfire, which contrast the serene unreality of dream and the harsh reality of war (Figure 1.2). The dreams end in high delirium.

On a symbolic level the sequence is highly illuminating: Ivan, as an innocent child, is unable to help his mother – he is deep inside the well trying to catch a star (a juvenile delusion). He can only passively observe the drama that is taking place at the top. Ivan subsequently climbs out of the well of childhood and launches his merciless revenge. The boy ceases to believe in human kindness and the possibility of happiness in general. He leaves his illusions at the bottom of the well. The well as such is an important artefact in Ivan’s Childhood, and the second dream is n...