![]()

1 WILDERNESS SPACES

‘Is it possible that landscape … is integrally connected with imperialism?’ asks W. J. T. Mitchell (2002a: 9). It is of course a rhetorical question. Mitchell’s essay inescapably links landscape – defined both as the visual representation of natural space and as the space thus represented (Mitchell points out the ambiguity in our use of the term) – with the violent exploitation of empire. It is not, he writes, a straightforward relationship, and despite claims that landscape art is ‘in its “pure” form a western European and modern phenomenon’ which emerges in the seventeenth and reaches its peak in the nineteenth century, its connections with imperialism stretch much further than the European empires of that period (ibid.: 7). The relationship of landscape to imperialism operates, suggests Mitchell, something like Freud’s ‘dreamwork’. Landscape, that is, visualizes, aestheticizes, harmonizes and finally narrativizes1 the uneasy combination of utopian fantasies and unresolved ambivalences and resistances in the imperial desire for mastery. Its seemingly untroubled gaze turns space into an ‘emblem of national and imperial identity’ (ibid.: 10, 17), veiling and naturalizing the violence that has produced it.

It is as precisely such an emblem that Rebecca Solnit views the ‘wilderness’ spaces depicted in American landscape art. But while Mitchell’s essay suggests, but does not state, the gendered nature of these imaginings, for Solnit it is central. Like Anne McClintock, who writes of British imperial narratives, Solnit emphasizes the centrality of the ‘myth of the virgin land’ to imperial fantasy – for her, fantasies of conquest of the American West. Its narratives, as McClintock argues, eroticize this ‘virgin’ space, so that territorial appropriation becomes sexual conquest. If the land is virgin, then ‘white male patrimony is violently assured as the sexual and military insemination of an interior void’ (1995: 30). For Solnit, it is this vision that characterizes Western landscape art, and in particular the paintings, photographs and cinematic depictions of the American West of which she writes. The wilderness spaces that they depict – virgin, blank, to be penetrated by civilization – are the subject of this chapter.

Imperial conquest

That American narratives of the conquest of its western frontier constitute a form of imperial fantasy is not a new idea. The writings of Frederick Jackson Turner, so influential in their insistence on the importance of the ‘frontier’ in the construction of American national identity, saw the United States as ‘an empire, a collection of potential nations, rather than a single nation’ (2014/1920). His vision of the frontier as ‘the meeting point between savagery and civilization’, of American history as the story of ‘the colonization of the great West’, and of the pioneer frontiersman, ‘fired with the ideal of subduing the wilderness’, who fights his way across the continent, ‘masterful and wasteful, preparing the way by seeking the immediate thing, rejoicing in rude strength and willful achievement’ (ibid.), is a vision of imperial conquest. It is Rudyard Kipling’s poetry Turner cites in his depiction of American character traits. Echoing McClintock’s analysis of British imperialism, then, Solnit describes American imaginings of its Western landscape in the same terms. This too, ‘the United States’ favorite story’, is a story of a virgin wilderness, ‘waiting to be deflowered, inscribed’ (2003: 94, 91).

In spite of his ‘rude, gross nature’, Turner’s Western man is ‘an idealist …. He dreamed dreams and beheld visions’, and had ‘unbounded confidence in his ability to make his dreams come true’. He was in short, a believer in ‘the manifest destiny of his country’ (Turner 2014/1920). The term Manifest Destiny is one whose origin is identified with American columnist and editor John L. O’Sullivan, whose series of articles from 1839 to the mid-1840s insisted that it was America’s ‘manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions’ (1845). It would be, he wrote, fulfilment of both God’s will and of ‘nature’s eternal, inevitable decree of cause and effect’ (1839). Like other forms of empire, then, America’s conquest and exploitation of its western spaces is seen as a religious quest, the search for a Promised Land, but it also has the force and inevitability of nature. Uniting the two is the concept of Manifest Destiny, which, though much contested and shifting in meaning, will be central to America’s national creation narrative and the cultural forms through which it will be imagined.2

Such conquest is a masculine exercise. ‘Frederick Jackson Turner’s frontiers’, writes Sandra Myres, ‘were devoid of women’ (1982: 8). Women, however, did appear in popular frontier fiction and illustrations, and in her study of ‘westering women’ of the nineteenth century, Myres details the dominant images of women to be found there, images that will later reappear in the cinematic Western. The first of these is ‘the refined lady of a sensitive and emotional nature’, who is ‘wrenched from home and hearth and dragged off into the terrible West’, where she is ‘condemned to a life of lonely terror among savage beasts and rapine Indians’ (ibid.: 1). Depictions of idealized white women, suffering, passive and noble, captured by savage ‘Indians’3 and sometimes rescued by heroic frontiersmen or saved by the intervention of a noble chief, were popular from the late eighteenth century (Luft 1982).

Myres’s second image is that of the ‘sturdy helpmate and civilizer of the frontier’. This figure, ‘her face wreathed in a sunbonnet, baby at breast, rifle at the ready, bravely awaited unknown dangers, and dedicated herself to removing wilderness from both man and land’ (1982: 2). She is competent, courageous and uncomplaining, but she is also a threat, since her presence destroys the homosocial environment in which frontiersman and ‘Indian’ could find a common bond in the ‘second paradise’ of the wilderness. Her arrival, with its imposition of domesticity and order, according to one historian meant the destruction of ‘something male in the race’ (in Myres 1982: 4).

Defined in opposition to the first two, the final image, that of the ‘bad woman’, encompassed a range of ‘deviant’ femininities: the masculinized wild woman, the ‘fallen’ sexualized woman, and the ‘foreign’ woman, often Spanish or Mexican, adept at ‘love, cooking, and often … gambling as well’. In contrast, black women were ‘almost invisible’ within popular fiction of the West, and ‘Indian women’ were simply ‘part of the wilderness that must be conquered and civilized’ (ibid.: 5).

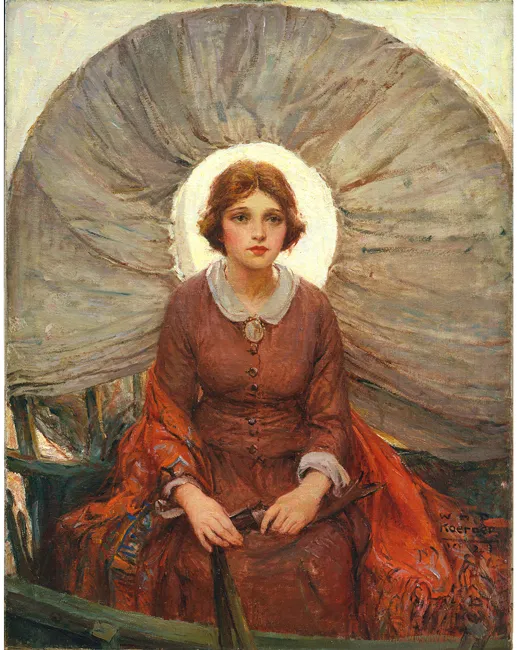

Underpinning all three images, writes Myres, lay the dominant ideal of femininity of the early to mid-nineteenth century: the cult of True Womanhood. According to Barbara Welter’s influential definition,4 the attributes of True Womanhood comprised the ‘four cardinal virtues – piety, purity, submissiveness and domesticity. Put them all together and they spelled mother, daughter, sister, wife – woman’ (Welter 1966: 152). Though focused initially on the northern white middle-class woman, representations of this idealized femininity circulated much more widely (Hewitt 2002: 159). We can see it in the figure of the saintly white woman – virgin or Madonna – captured by ‘Indians’, which was so common in popular fiction. In art it was realized in the figure of the ‘Madonna of the prairie’, most famously depicted in Koerner’s painting of 1921, in which the arc of the covered wagon forms a halo above the head of the young woman holding its reins, as she gazes out towards the Western frontier.5

As Myres’s account makes clear, however, such stereotyped depictions struggled to contain a changing economic, social and cultural situation that was far more complex and contested. Jane Tompkins, indeed, has argued that what she calls the ‘deauthorization of women’ (1992: 42) that characterizes the Western myth should be seen as a response not to women’s absence but to their increasing power, not only as moral guardians within the home – in line with ideals of ‘True Womanhood’ – but also outside it. Historically, 1848 marked the end of the Mexican-American War, the resulting annexation of California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Wyoming and Colorado, and the apparent fulfilment of O’Sullivan’s ‘manifest destiny’ claims. But 1848 is also the year of the first women’s rights convention and the resulting Seneca Falls Declaration, which urged ‘zealous and untiring efforts … for the securing to women an equal participation with men in the various trades, professions, and commerce’ (in Schneir 1972: 82).6 The first state to grant voting rights to women was Wyoming, and it did so in 1869.7 From their beginning, then, the images of ‘westering women’ that Myres describes, and the ideal of ‘true womanhood’ on which they were based, were both powerful and contested.

FIGURE 1.1 W. H. D. Koerner, Madonna of the Prairie (1921).

Landscape and the Western

Two genres, argues Solnit, have been crucial in shaping the popular imagination of the American West: ‘nature photography and Western movies’ (ibid.: 99). Her own topic is the first of these, and she recounts the way in which the West was ‘invented’ through nineteenth-century landscape photography, much of it in the service of government surveys. The Western desert is, she writes, a ‘place without language, to some extent unnamed, unmapped, unfamiliar’ (ibid.: 75). On it has been imposed a religious narrative, so that if the East is ‘where history, God and religion come from, the West is where they are supposed to go, a place always lying ahead, the territory of what is yet to come’ (ibid.: 69). Its landscape becomes both a Promised Land and an Eden: a paradise which offers both a return to the ‘unspoiled innocence’ of a mythical past and the setting for a future heroic exploitation whose profit will derive, precisely, from the violation of that innocence. Joel Snyder, like Solnit, traces this vision through the landscape photography of the mid-nineteenth century, but he also points out that this new medium fed the expectations of an audience already exposed to ‘stories and pictures romanticizing the frontier and inflating the promise of wealth and self-sufficiency that lay just beyond the frontier’ (2002: 190).

If, then, as Solnit writes, ‘the West became the first region a culture will know largely through the photographic’ (2003: 70), the images through which it was represented, with their combination of ‘gardenlike grace and breathtaking grandeur’ (Snyder 2002: 185), were composed according to the romantic fantasies of early American novelists and travellers, whose tales would be used to lure potential westward migrants. James Fenimore Cooper’s Leatherstocking novels, which pit the solitary frontiersman Natty Bumppo against the ‘civilizing’ forces of westward exploration and its destruction of the ‘virgin’ wilderness that is also what attracts it, were published between 1823 and 1841. Like the contemporary paintings described by Martha Levy Luft, the second of the novels, The Last of the Mohicans (1826), features the capture of white girls by ‘Indians’. By 1847, Francis Parkman’s influential The Oregon Trail; being sketches of prairie and Rocky Mountain Life was being published, with its descriptions of ‘fine athletic’ frontiersmen, vast and strange landscapes, and exotic ‘savage Indians’, but its descriptions had been preceded by those of gazetteers and guidebooks, newspaper and magazine articles, and popular fiction. Landscape, writes Annette Kolodny, ‘is the most immediate medium through which we attempt to convert culturally shared dreams into palpable realities’ (1984: xii), and the stuff of these dreams concerned ‘the productivity of the soil, the luxuriant forests, and rich mineral resources of the Western lands’ – once the ‘Great American Desert’ had been crossed (Myres 1982: 15–16).

But it is through ‘the scenery that flashes by in thousands of Hollywood Westerns’ that more recent audiences are familiar with this landscape (Mitchell 2002b: 268), and with the dreams it embodies of ‘the nation’s infinite possibilities and limitless vistas’ (Schatz 1981: 46). The Western, as Tom Conley writes (2006: 293), is ‘a spatial genre par excellence’. Through its invocation of landscape, the Western continues the ideological themes of nineteenth-century American popular culture, with its repeated working through of a national creation narrative. For Thomas Schatz, these repeated mythic narratives, like the popular fiction and photography before them, operate to ‘“naturalize” American policies of Western expansion and Manifest Destiny’ (ibid.: 47), presenting a ‘purified form of the national narrative’ (Campbell 2013: 21). Its narratives constantly replay Frederick Jackson Turner’s vision of the nation-making process of internal colonization. Their logic is clear: from ‘the “blank spaces” of the western lands was created, forged, and inscribed a grid of human inhabitation, settlement, and narrative’ (ibid.: 11).

This idea of the Western landscape as a ‘blank space’ is developed by Jane Tompkins. ‘The typical Western’, she writes, ‘opens with a landscape shot’: of a blank horizon above prairie or desert, sometimes with solitary rider or wagon train in the distance. ‘All there is’, she continues, ‘is space, pure and absolute’ (1992: 69–70). It is a landscape, she argues, that ‘reflects the Old Testament sense of the world at creation’. Above all, it is ‘a land defined by absence: of trees, of greenery, of houses, of the signs of civilization, above all, absence of water and shade’ (ibid.: 71). In the wagon train stories this is the desert to be crossed on the journey to the fertile valley; in other narratives it is simply the space of trial, where the hero proves his manhood and from which he perhaps rescues the white woman.8 Its openness, she writes, ‘flatters the human figure by making it seem dominant and unique, dark against light, vertical against horizontal, solid against plane, detail against blankness’ (ibid.: 74). It thus appears not only as empty space but as stage. On it the hero performs masculine power: he ‘can conquer it by traversing it, know it by standing on it’ (ibid: 75).

This is, of course, a rhetorical strategy, one that functions to naturalize the code of values that the Western celebrates. In fact, ‘the desert is no more blank or empty than the northeastern forests were when Europeans came. It is full of living things, … and inhabited by people’ (ibid.: 76). Its constructed blankness invites both domination and the writing, on its tabula rasa, of the story of a hero and a nation. This blankness and passivity position the Western landscape as feminine, as Solnit and Kolodny also suggest: the hero ‘courts it, struggles with it, defies it, conquers it, and lies with it at night’ (ibid.: 81). But Tompkins also argues that its function is to displace the ‘feminine’ values of civilization that the hero rejects, substituting for them the struggle with a desert that represents a transcendent asceticism rather than a feminine embrace. Women themselves, she argues, are repressed in the Western, as are the ‘Indians’ with which we identify it: as people, both are absent. Women provide the motive for male activity, but the values they represent – love, forgiveness and home – are associated with weakness and excessive verbalization. In John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), i...