eBook - ePub

Available until 26 Feb |Learn more

Fact Vs. Fiction

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in the Age of Fake News

This book is available to read until 26th February, 2026

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 26 Feb |Learn more

Fact Vs. Fiction

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in the Age of Fake News

About this book

Help students discern fact from fiction in the information they access not only at school but in the devices they carry in their pockets and backpacks.

The advent of the 24-hour news cycle, citizen journalism and an increased reliance on social media as a trusted news source have had a profound effect not only on how we get our news, but also on how we evaluate sources of information, share that information and interact with others in online communities. When these issues are coupled with the “fake news” industry that intentionally spreads false stories designed to go viral, educators are left facing a new and challenging landscape. This book will help them address these new realities, providing strategies and support to help students develop the skills needed to effectively evaluate information they encounter online.

The book includes:

The companion jump start guide based on this book is Fighting Fake News: Tools and Strategies for Teaching Media Literacy.

Audience: K-12 educators

The advent of the 24-hour news cycle, citizen journalism and an increased reliance on social media as a trusted news source have had a profound effect not only on how we get our news, but also on how we evaluate sources of information, share that information and interact with others in online communities. When these issues are coupled with the “fake news” industry that intentionally spreads false stories designed to go viral, educators are left facing a new and challenging landscape. This book will help them address these new realities, providing strategies and support to help students develop the skills needed to effectively evaluate information they encounter online.

The book includes:

- Instructional strategies for combating fake news, including models for evaluating news stories with links to resources on how to include lessons on fake news in your curricula.

- Examples from prominent educators who demonstrate how to tackle fake news with students and colleagues.

- A fake news self-assessment with a digital component to help readers evaluate their skills in detecting and managing fake news.

- A downloadable infographic with mobile media literacy tips.

The companion jump start guide based on this book is Fighting Fake News: Tools and Strategies for Teaching Media Literacy.

Audience: K-12 educators

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education Standards

Facts Are So 2015:

Why This Book? Why Now?

post-truth /ˌpəʊs(t)ˈtruːθ/

adjective

Relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.

“in this era of post-truth politics, it’s easy to cherry-pick data and come to whatever conclusion you desire”

“some commentators have observed that we are living in a post-truth age.” (“Oxford Living Dictionaries,” n.d.)

Every year, Oxford Dictionaries selects a word as Word of the Year. In addition to being a word that was used extensively during the previous 365 days, the chosen word also reflects the “mood and preoccupations” of the passing year. In 2016, that word was post-truth. According to the editorial staff, research conducted by Oxford Dictionaries revealed that use of the word had increased by approximately 2,000% over its usage in 2015 (“Word of the Year,” 2016).

And yet, unlike previous choices for Word of the Year, the selection of post-truth seemed rooted as much in the future as it was in the year that had just passed. Indeed, in the time since Oxford Dictionaries declared that our vocabulary had expanded to encompass the new world in which facts no longer seemed to matter, our concern and befuddlement over the spread of misinformation has continued to grow.

The Edelman Trust Barometer is an annual survey of 28 countries around the world that offers a glimpse into the amount of trust people place in their countries’ governments, media, businesses, and so on. In the 2018 survey, 59% of respondents said they did not trust what they saw represented as news in the media, and 63% said they did not believe the average person had the skills to discern real news stories from those that were fake. As Stephen Kehoe, global chair of reputation at Edelman, told CNBC when the survey data was released, “In a world where facts are under siege, credentialed sources are proving more important than ever. There are credibility problems for both platforms and sources. People’s trust in them is collapsing.” His assertion was supported by the data: 65% of those surveyed included social media sites and search engines as their news source, but trust in those platforms decreased in 21 of the 28 countries Edelman surveyed (Edelman, 2018).

In the U.S. in particular, this distrust extended to government agencies as well, with only 33% of respondents indicating they trusted government resources. This erosion of trust by Americans in both their government and a free press, one of the hallmarks of the country’s democracy, was not lost on those responsible for collecting this data, whose summary of the results included this call to arms:

It is no exaggeration to state that the U.S. has reached a point of crisis that should provoke every leader, in government, business, or civil sector, into urgent action. Inertia is not an option, and neither is silence. The public’s confidence in the traditional structures of American leadership is now fully undermined and has been replaced with a strong sense of fear, uncertainty and disillusionment. (Edelman, 2018)

And so, we find ourselves living a post-truth world, where “alternative facts” and “fake news” dominate our discussions and compete, often winning, against once authoritative and mainstream information sources. Why is this happening? Naturally, the answer is complex and varies depending on whom you ask. It’s tempting, of course, to blame technology, for, indeed, the internet and the penetration of smartphones into our everyday lives have amplified the problem. (In later chapters, we’ll explore how technology hastened the advent of an entire industry devoted to deception, while also offering some of the best tools available to help us dig ourselves out of this hole.) It’s also tempting to point the finger at an increasingly ignorant populace and to long for the “good old days” when people were smarter and more virtuous, or to view our ability to be fooled by increasingly slick propaganda as a personal failing. For now, however, rather than focusing on how we got here, let’s consider the consequences of this strange and uniquely 21st-century journey.

Nothing You Can Say Will Convince Me Otherwise

In the days leading up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election, many news organizations spent time interviewing likely voters, asking them why they’d chosen to cast their votes for a specific candidate. Jennifer remembers watching one such interview in which a decided voter passionately cited a story that already had been debunked numerous times. The story linked former Secretary of State and presidential candidate Hillary Clinton to a child trafficking ring. When the reporter confronted the voter with examples of how that story had been proven false, the voter simply dug in rather than consider the reporter’s view and said, “nothing you can say will convince me otherwise.” When faced with empirical evidence, this voter chose to put her faith in her own beliefs. What’s more, she’s not alone.

Numerous psychological studies, over several decades, have concluded that when faced with facts that dispute deeply held beliefs, people overwhelmingly search for ways to discredit those facts while clinging to the personal narratives that support the things they believe to be true (Kolbert, 2017). Couple this with a political climate of near toxic polarization, and you’re left with a recipe that spells disaster for logic and reason. But it doesn’t end there. In addition to being unwilling to consider explanations that do not support our own biases, we’re also far more willing to share information that does support our beliefs—without vetting that information for accuracy.

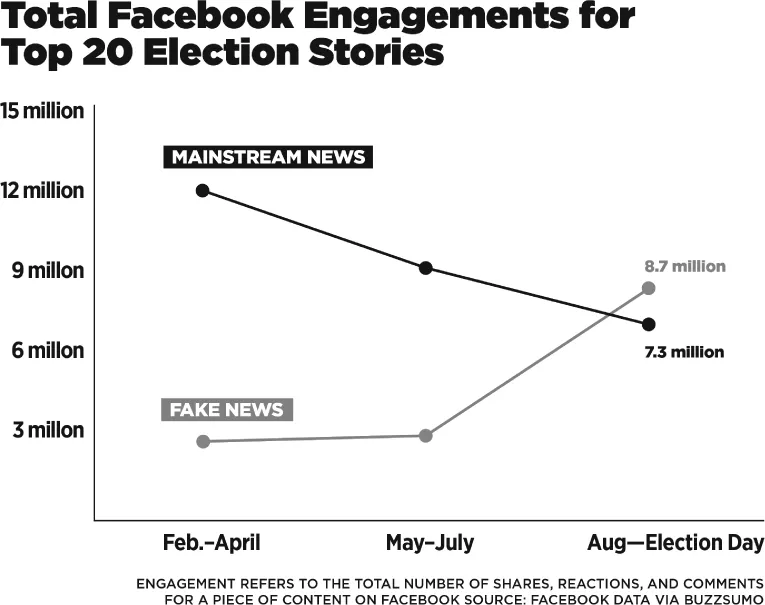

Figure 1.1 Despite the fact that most people consider themselves savvy at detecting fake news, an analysis by BuzzFeed revealed that Facebook users shared more fake news stories than real ones in the run up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

In November 2016, an analysis conducted by the site BuzzFeed News (Figure 1.1) found that the top fake election news stories (stories that were proved to be false by independent analysis) generated more total engagements (Likes and shares) on Facebook than the top election stories from nineteen major news outlets combined (Silverman, 2016).

What’s more, because social media outlets, such as Facebook and Twitter, allow users to unfollow people whose postings contradict their own beliefs without ever notifying the other people that they’ve been unfollowed, there’s no social consequence for removing differing opinions from your information stream. Without the risk of an awkward, potentially embarrassing, or even confrontational conversation, we can eliminate the inconvenience of contradictory opinions from our online lives with just a few clicks.

Of course, this happens, to some degree, without us having to be complicit at all. In 2018, Facebook CEO, Mark Zuckerberg was called before the U.S. Congress to testify about the revelation that the private data-collection company Cambridge Analytica had gathered information from up to 87 million of Facebook’s users without their knowledge. In total, Zuckerberg testified for over ten hours and faced nearly 600 questions, this one from Republican Senator Roger Wicker: “There have been reports that Facebook can track users’ internet browsing history even after that user has logged off of the Facebook platform. Can you confirm whether or not this is true?” Although the Facebook CEO didn’t answer the question directly, instead promising to have his team get back to the senator later, he did mention that cookies (the bits of information that web servers collect, store, and pass to your browser as you visit different sites on the internet) may make that possible.

In his 2011 book and corresponding TED Talk, “The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You,” Eli Pariser warns us all about how the internet uses the data it collects while we surf the web to not only sell us things, but also to hide information from us that we find uncomfortable or that doesn’t align with the opinions our clicks and Likes seem to support. Over the years, these algorithms have become more sophisticated and better at doing their job, which is to tailor the internet experience to a specific user’s interests and beliefs. As a result, retail companies are better equipped to show us ads for things we might actually purchase, and companies like Cambridge Analytica can use a “personality quiz” to identify potentially sympathetic voters who may be worth targeting by a specific political party or candidate. At the same time, this increased sophistication also means that we are far less frequently confronted by ideas or viewpoints that don’t match our own, making us less and less capable of having a reasonable discussion involving divergent points of view. In the end, whether or not we actively participate in our own insulation from ideas we disagree with, the internet has evolved to help this process along.

So what does this have to do with fake news?

A 2017 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center recorded that 67% of Americans get at least some of their news from social media. The same poll indicated that news consumption via Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Snapchat, and other social media sites was on the rise in demographic groups such as older people, non-Whites, and those with limited education, who have historically relied on more traditional sources of information (Shearer & Gottfried, 2017). Although these trends clearly present a problem when taken in the context of how our social media feeds are both intentionally and unintentionally filtered to support our own biases, they also present an opportunity for political parties and those whose personal and professional goals center around getting candidates elected. With more people turning to their own, increasingly biased, social media feeds for news, those feeds become fertile ground for planting stories that look a lot like legitimate news but don’t require the same kind of vetting that traditional journalism relies on.

Many people in the public eye, including politicians at the highest level of the U.S. government, have further capitalized on this hamster wheel of bias and disinformation. Rather than railing against the notion of fake news and seeking to support the validity of their own opinions or policies with facts and data, those in power use the term as a label with which to discredit those who disagree with them or whose data contradicts theirs. Indeed, as of January 2018, President Trump had been recorded using the term fake news to describe traditional news outlets over 400 times since his inauguration (Stelter, 2018). Intentional or not, one consequence of this very public repetition of the term makes every successive use less effective than the last. Put another way, as the Liar’s Paradox goes: “When everything is false, nothing is false.” The more we consider news to be suspect, the more all news sources, regardless of their journalistic integrity and editorial oversight, become equally suspect as well. For those who rely on disinformation to further an agenda, this seems like a preferable outcome.

Where Do Educators Fit in a Post-Truth World?

Early in George Lucas’ Star Wars (1977), Imperial forces capture a rebel ship. While listening to the ominous explosions and awaiting the inevitable arrival of the white-armored stormtroopers to spill into the hallway where they stand, the universe’s most erudite droid, C-3PO, turns to his companion R2-D2 and says simply, “We’re doomed.” We know how he feels. It’s tempting to look at the situation we’ve found ourselves in and feel hopeless. But as two people who have spent a lot of time studying the phenomenon of fake news, we are (cautiously) optimistic. What’s more, we believe that, in the end, educators hold the keys to getting us out of this mess.

In a world in which facts are considered passé and an entire industry exists to deceive information consumers, the abilities to discern fact from fiction and to respond productively to those who counter data with belief are critical skills. Although the delivery methods have changed and a focus on standardized testing in math and English have reduced instructional emphasis on literacy, history, and civics, educators have always been information conduits and experts at helping students gain strategies to locate reliable sources. As the amount of information being generated has increased exponentially and the ways in which we access it have become less regulated, we all have to ask ourselves, “Are average educators prepared to shift from teaching basic information literacy to being fierce defenders of truth?”

We think so. In fact, we see skilled teachers as the kryptonite against fake news and the purveyors of a better democracy. In the pages ahead, we hope to further unpack the challenges before us, outline ways for educators to help their students become smarter consumers of information than we have proven to be, and highlight examples in which practitioners are already leading the way for us.

Chapter 1

1. What’s your why? In this chapter we shared some of the reasons why we felt a sense of urgency to write this book. What is your current motivation for wanting to help your students grow as information consumers and critical thinkers in the age of fake news?

2. Think about all the information presented in this chapter and take a minute to identify which pieces are, to you, the most urgent. Now think about your school or district. With whom would you most like to have a conversation about the information you prioritized? What would that conversation look like?

3. Tweet us! Yay! Your school has decided to hold a monthly Twitter chat aimed at parents and other community members. And there’s more great news! This month the topic is media literacy. What are some Tweets you’d share on the night of the chat to help families better understand the phenomenon of fake news?

Share your thoughts and reflections with us: @jenniferlagarde and @dhudgins #factvsfiction

Fake News: The Great Human Tradition

And we now find that it is not only right to strike while the iron is hot, but that it is very practicable to heat it by continual striking.

—Benjamin Franklin

Although the global nature of the internet, and its dominance as the primary means by which we get information, allows purveyors of all sorts of lies and misinformation to deceive people on a massive international scale, the problem of fake news is hardly a new one. In fact, fake news has been a part of American story since the Founding Fathers dreamed of a republic free from colonial rule.

In 1782, Benjamin Franklin, who was worried that the colonies would reconcile with Great Britain and arrive at a peaceful end to the American Revolution before achieving true independence, created an entirely fake “supplement” issue of an actual Boston newspaper, the Independent Chronicle. In it, Franklin wrote a grisly and salacious story about the supposed discovery of more than 700 “scalps of our unhappy country folk” by colonial soldiers. According to the story, these gruesome spoils of war were th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About ISTE

- About the Authors

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Facts Are So 2015: Why This Book? Why Now?

- Chapter 2: Fake News: The Great Human Tradition

- Chapter 3: Fake News in an Exponential World

- Chapter 4: Our Brains on Fake News

- Chapter 5: Fake News Self-Assessment

- Chapter 6: All Is Not Lost! Resources for Combatting Fake News

- Chapter 7: Voices from the Field

- Chapter 8: Critical Thinking Now More Than Ever

- References

- Index

- Back Cover

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fact Vs. Fiction by Jennifer LaGarde,Darren Hudgins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Standards. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.