Fact Vs. Fiction

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in the Age of Fake News

Jennifer LaGarde, Darren Hudgins

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Fact Vs. Fiction

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills in the Age of Fake News

Jennifer LaGarde, Darren Hudgins

About This Book

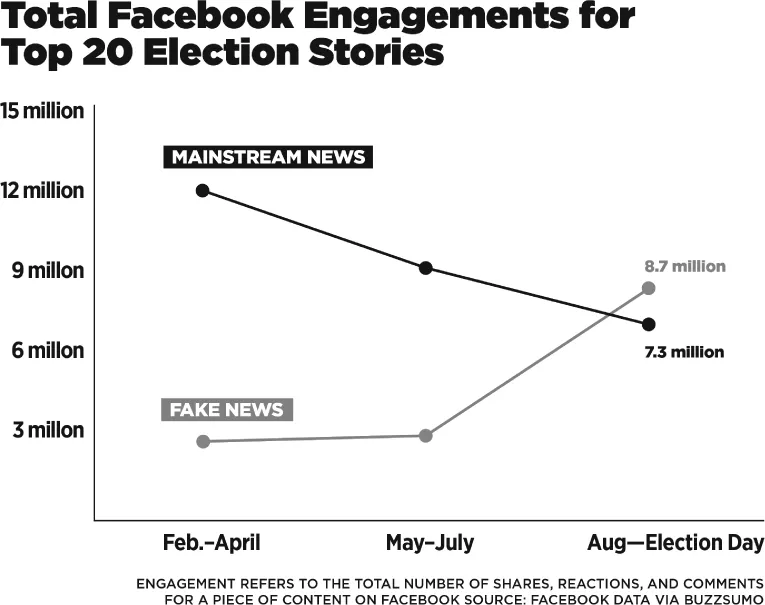

Help students discern fact from fiction in the information they access not only at school but in the devices they carry in their pockets and backpacks. The advent of the 24-hour news cycle, citizen journalism and an increased reliance on social media as a trusted news source have had a profound effect not only on how we get our news, but also on how we evaluate sources of information, share that information and interact with others in online communities. When these issues are coupled with the "fake news" industry that intentionally spreads false stories designed to go viral, educators are left facing a new and challenging landscape. This book will help them address these new realities, providing strategies and support to help students develop the skills needed to effectively evaluate information they encounter online.The book includes:

- Instructional strategies for combating fake news, including models for evaluating news stories with links to resources on how to include lessons on fake news in your curricula.

- Examples from prominent educators who demonstrate how to tackle fake news with students and colleagues.

- A fake news self-assessment with a digital component to help readers evaluate their skills in detecting and managing fake news.

- A downloadable infographic with mobile media literacy tips.

The companion jump start guide based on this book is Fighting Fake News: Tools and Strategies for Teaching Media Literacy. Audience: K-12 educators

Frequently asked questions

Information

Facts Are So 2015:

Why This Book? Why Now?

Nothing You Can Say Will Convince Me Otherwise

Where Do Educators Fit in a Post-Truth World?

Chapter 1