- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

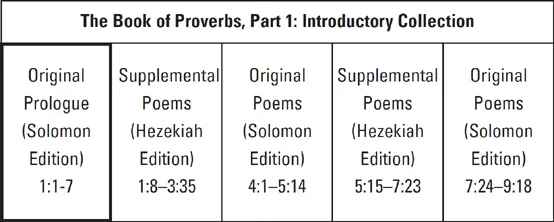

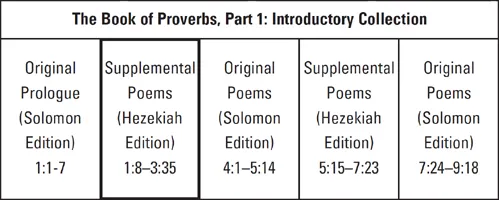

The uniqueness of this commentary is its detailed, first-time uncovering of evidence that there were two editions of Proverbs, the first in the time of Solomon and the second in support of King Hezekiah’s historic religious reforms. In this light heretofore puzzling features of the book's design, purpose, and message are clarified in this light and the book's relevance for its time and ours greatly enhanced.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Proverbs by John W. Miller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Biblical Commentary. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Introductory Collection

Proverbs 1:1-7

Original Prologue

(Solomon Edition)

PREVIEW

Prologues like this were typical of instruction manuals in ancient Egypt (for another example, see the 22:17-21 prologue to the sayings in 22:22-24:22). The Solomon Edition prologue is a single sentence (in Heb.) that identifies the collection’s origins and purpose (1:1-4, 5). The Hezekiah Edition editors added two inserts, the first in 1:5 to indicate a wider readership for their new edition of the book, and the second at the end (1:7) to clarify its presuppositions.

OUTLINE

Heading, 1:1

Purpose Statement (with Insert), 1:2-6

Watchword (Insert), 1:7

EXPLANATORY NOTES

Heading 1:1

The first word of the Prologue (proverbs) refers to poem-like compositions (měšālîm) that were designed to teach a lesson. The poems that follow are ascribed to Solomon son of David, King of Israel (1:1). Solomon might well have written many of the poems in the book’s initial edition; in any case, Israel’s historians recount that he was renowned for his wisdom and literary output (1 Kgs 4:29-34). His role in the production of this book is also indicated in Proverbs 4:1-3, which followed the Prologue in the book’s first edition [Solomon Edition]. There Solomon states that the teachings following in 4:4-5:6 are a verbatim report of what his father taught him when he was in his father’s house, still tender, and an only child of my mother (4:3). Solomon follows these teachings with words of his own, in 5:7-14 (for additional comments on Solomon’s role in creating the book’s first edition, see notes on 4:1-5:14, the Overview to the Main Collection in 10:1-22:16, and the essay Genre Issues).

It is sometime said that the book of Proverbs is devoid of references to Israel [Modern Study]. This is true of its teachings, which like those in other manuals of this type are transcultural in their orientation (cf. 8:4). But still, the book’s heading is explicit about its teachings being sponsored or perhaps authored by Solomon son of David, king of Israel (see also the reference to Hezekiah king of Judah, 25:1). The book is thereby linked to the teachings of an Israelite king whose reign is memorialized in the annals of his people as one of the most important in its history (cf. 1 Kgs 2:12-11:42).

Purpose Statement (with Insert) 1:2-6

Four of the verses that follow (1:2, 3, 4, 6) begin with infinitive verbs that connect them to each other and verse one (1:1). They state what the book’s general purpose is (1:2-3a), its subject matter (1:3b), its intended audience (1:4), as well as its study methods (1:6). Its general purpose is for attaining (lit., knowing) wisdom and discipline (1:2a). Wisdom (hokmah) is competence and skill “in any domain” (Fox: 32); discipline (musiar) is the educational process required for attaining such competence. This entails understanding words of insight (1:2b). The verb understanding and the noun insight are related to the preposition “between” (in Heb.) and “signify the ability to draw proper distinctions” (Cohen: 1). Developing these skills enables one to acquire a disciplined and prudent life (1:3a; lit., “the discipline of insight,” Fox). Three words in 1:3b identify the desired outcomes of such an education: doing what is right (sedeq, personal uprightness); upholding what is “just” (mišpāt, societal justice), and being fair and honest (mēšārîm, integrity in community relations).

The more specific goal of this manual is to give prudence to the simple, knowledge and discretion to (lit.) a young man (1:4b). The young man referred to is not a child, but an older youth like the one in the story recounted in chapter 7. He is not necessarily evil or rebellious. He is simply thoughtless and lacking experience (lit., lacks heart, 7:7b). He needs to be educated. He needs to be taught (lit., given) prudence (‘ormiah, discretion), knowledge (da‘at), and common sense (mezimHh). The method to be used in educating him is briefly alluded to in 1:6. It entails understanding diverse types of literature: a thought-provoking poem (mashal), a metaphorical saying (Hab 2:6), insightful words of the wise, enigmas or riddles (Ps 49:4-5)—in short, the kind of “words” that follow in this book [Words for Wisdom and Folly].

The Hezekiah Edition added verses 1:5 and 1:7. Thus 1:5 begins with an imperative that breaks the flow of infinitives (in 1:2, 3, 4, 5). It targets a second group for its teachings, the wise and discerning, and asks that they add [them] to their learning and get guidance. The sayings of these wise are referred to elsewhere (1:6; cf. 22:17; 24:23). Their teaching is characterized as a fountain of life (13:14). So why would they too be told to listen to this book’s teachings and add them to their learning? This unusual request implies that the book contains teachings with which they are not yet familiar, precisely the case when the Hezekiah Edition was first published [Distinctive Approach]. The Hezekiah Edition was not just directed to young men but also to the professional teachers of the time (for further on this group, see 5:13; 30:1-7; Isa 5:21).

Watchword (Insert) 1:7

The watchword in 1:7 (The fear of the LORD is the beginning [rē’šît] of knowledge) is one of the most important additions made to the book at the time the Hezekiah Edition was created (see Introduction, “Purpose and Design of the Hezekiah Edition”). It appears again in modified form in 9:10, forming an “enclosure” for the introductory teachings of this edition. It is repeated at the heart of the Main Collection in 15:33 but elsewhere only in Psalm 111:10 and Job 28:28 (and there in a truncated form with a different meaning). It carefully reformulates the statement that stood at the forefront of the Solomon Edition [Solomon Edition], which declares (lit.), The beginning [rē’šît] of wisdom [is]: get wisdom (4:7). The key word rē’šît (beginning) in both sentences (1:7a and 4:7a) is best understood as “the temporal starting point” (Fox: 68; cf. 9:10; 15:33; Gen 1:1). In another Solomon Edition poem, wisdom describes herself as existing from the beginning (rē’šît) of creation (8:22-23). This is why (in the Solomon Edition poems) wisdom is more important than anything else (8:11), and the beginning of wisdom is to get wisdom (4:7). The Hezekiah Edition insert in 1:7 takes issue with this Solomon Edition watchword. There is something prior to wisdom that is the beginning of wisdom, namely, fear of Yahweh. Acquiring wisdom remains the overall objective of this new edition of Proverbs, but another starting point for acquiring it is hereby announced: the fear of Yahweh (1:7a). The watchword’s second line (but fools despise wisdom and discipline, 1:7b) clarifies that this new starting point in no way modifies the book’s original purpose. The book remains a manual for attaining wisdom and discipline as stated in 1:2a, only that the fear of Yahweh is the new starting point for acquiring it.

What is meant by fear of Yahweh? In Deuteronomy, possibly also published at this time [Hezekiah Reform Literature], the phrase fear of Yahweh is used to characterize those who honor, love, trust, and pray to the God of Israel and obey his teachings as revealed through Moses (Deut 5:29; 6:2; 8:6; 10:12-13; 31:12-13). The psalms of the Psalter’s first two books (Pss 1-72, likely also published at this time) include numerous references to those who fear Yahweh. Examples are Psalm 25:14 (lit., “the secret of Yahweh is with those who fear him and his covenant for their understanding”) and 33:18 (“But the eyes of the LORD are on those who fear him, on those whose hope is in his unfailing love”). Those who fear Yahweh “turn from evil and do good; seek peace and pursue it” (34:14). “The law of his God is in his heart” (37:31).

It is reasonable to think (contra Whybray, 1995:136-40) that the phrase fear of Yahweh in the Hezekiah Edition of Proverbs has the same meaning that it has in the other writings of the period. Here too (in Proverbs) it signifies respect for the God who revealed himself at Horeb, from whose mouth come knowledge and understanding (2:6). Here too (in Proverbs) the reference is to the knowledge of God that was the heritage of those in Israel who were faithful to the teachings of Moses—which is more or less what the corresponding version of the watchword in 9:10 makes clear. In 9:10, the first line of the saying is similar to the one in 1:7a: The fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom (9:10a); but then a second line declares, and knowledge of the Holy One is understanding. In this two-line statement fear of the LORD and knowledge of the Holy One are parallels, making a statement regarding the relationship of reverence for Yahweh (which equals knowledge of the Holy One) to the pursuit of wisdom: knowledge of this kind is understanding (9:10b). In other words, it also qualifies as knowledge of a kind that fosters wisdom for making right choices. This too is what Agur son of Jakeh declares in the only other place in the Bible where the phrase knowledge of the Holy One appears (cf. 30:2-6; for similar terms and message, see Hos 4:4, 6; 11:12).

THE TEXT IN BIBLICAL CONTEXT

Revelation and Reason

The LORD referred to in the watchword in 1:7 is the God who was revealed to Israel in a manner described in Deuteronomy 5. There we read of the Decalogue spoken in the hearing of all the people. The first commandment of the Decalogue specifies that Israel shall worship Yahweh only. The “fear of the Lord” as described in that chapter is an emotion of awe that is so great that his people will want to obey his commandments (5:28-29). In Proverbs this awe or fear of the LORD is viewed as the beginning of an educational process that includes acquiring knowledge and discernment in the thoughtful manner advocated in the proverbs of Solomon (1:1-4). This involves acquiring knowledge and discernment by reflecting on the words of the wise, whether those of Solomon or others. Awe for God and studying in this way are viewed as complementary and mutually enriching approaches to becoming wise. Reverence for God and his commandments is the beginning of wisdom, not a replacement for other kinds of study (but fools despise wisdom and discipline, 1:7b).

However, in the two places in the Bible outside of Proverbs where this watchword is cited (Ps 111:10; Job 28:28), we can sense other nuances emerging. In Psalm 111:10 the statement that “the fear of the LORD is the beginning of wisdom” appears at the end of a recitation of God’s mighty works in redeeming Israel and establishing his “covenant forever” (111:9). In other words, in this instance the watchword stands alone in the context of God’s special deeds in redeeming Israel and is no longer situated in the context of the wisdom poems of Solomon. The conclusion drawn in Job 28 is that the “fear of the LORD” is the only place where wisdom can be found (28:28). This point is driven home in the prior verses of the poem in this chapter: no matter how hard one tries, wisdom can be found nowhere else.

At some point in Israel’s postexilic experience, this regard for the “law of the LORD” emerged as the supreme and exclusive source of wisdom (cf. Ps 119:98-100). In this manner, a tension opened up between revelation and reason in biblical tradition that one does not sense exists within the teachings of Proverbs. This tension was resolved in various ways in “early Judaism” and in the Scriptures of the NT [Wisdom of Proverbs].

THE TEXT IN THE LIFE OF THE CHURCH

Reason and Revelation

Through the centuries Israel and the church have had to struggle with the revolutionary implications of new experiences and new discoveries. One such critical moment for Israel was the advent of the life and mission of Jesus Christ and the church begun in his name. Was his wisdom about life better than that of the scribes and Pharisees, as Matthew’s Gospel asserts (Matt 5:20)? Was he in some sense the incarnation of the wisdom that Proverbs speaks of—a “word” that was with God from the beginning of time, as John’s Gospel proclaims (John 1:1)?

A challenge of another kind was posed for the Christian church itself by the revolutionary discoveries of Copernicus and Galileo about our cosmic home. Since then, inquiring minds have uncovered one mystery after another in virtually every domain of God’s universe. Perhaps the book of Proverbs has something yet to teach us about how these various “revelations” and discoveries can be embraced and unified.

In a study attempting to convey what Proverbs’ contribution might be in this regard, Daniel J. Estes draws a helpful distinction between a “worldview” and a “full-blown philosophy of life.” What we have in Proverbs, he implies, is not so much a “full-blown philosophy of life” as a “worldview.” A worldview, he writes is made up of “the beliefs, attitudes and values that cause a person to see the world in a certain way.” It asks, among other things, “What is prime reality—the really real?” “What is the nature of external reality, that is, the world around us?” (20). In his discussion of the “worldview” of Proverbs, Estes presents the thesis that its teachings are “fundamentally connected to the rest of the Hebrew Bible” and to those in particular that view God as the Creator whose control over the world is “continuing, active and personal” (26).

In other words, “the universe is not arbitrary,” Estes writes, “for Yahweh has constructed it with recognizable design. Neither is the world amoral, for Yahweh’s order is intimately related to his righteous character” (29). Furthermore, “the modern dichotomy between secular life and religious faith, or between the profane and the sacred, is foreign to the worldview” of this book. “In Proverbs, the juxtaposition of the routine details of daily life with reminders of Yahweh’s evaluation of these activities (cf. Prov 3:27-35) reveals that all of life is regarded as a seamless fabric” (25).

Proverbs 1:8—3:35

Supplemental Poems

(Hezekiah Edition)

PREVIEW

This is the first block of supplemental poems added when the Hezekiah Edition was created [Distinctive Approach]. When adding these poems, the editors displaced a block of Solomon Edition poems (4:1-5:14) from its position at the book’s beginning to where it is now [Solomon Edition]. Both blocks of poems (those added in 1:8-3:35 and the Solomon Edition poems in 4:1-5:14) address similar issues: how urgent it is that young men do not fall in with lawless violent companions; the absolute necessity of being attentive to the voice of wisdom and heeding the counsel of one’s father if one is going to have a happy and successful life; and the tremendous benefits that do in fact ensue from following wisdom’s path. The poems added by the men of Hezekiah at this point also touch on themes that were not addressed in the Solomon Edition: trusting Yahweh to direct one’s path and heeding his words. By comparing the teachings inserted by the Hezekiah editors with those in the older Solomon Edition, we can gain an unders...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Abbreviations/Symbols

- Contents

- Series Foreword

- Author’s Preface

- Introduction to the Book of Proverbs

- Part 1: Introductory Collection

- Part 2: The Main Collection (Themes)

- Part 3: Supplemental Collections

- Outline of Proverbs

- Essays

- Map of Old Testament World

- Bibliography of Works Cited

- Selected Resources

- Index of Ancient Sources

- The Author