- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

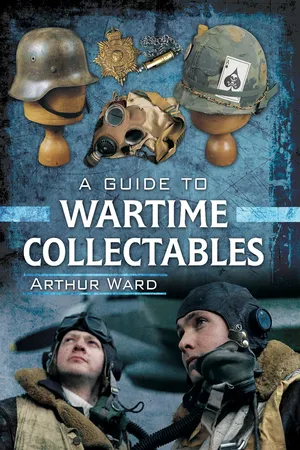

A Guide to Wartime Collectables

About this book

Make sure you're getting the genuine article with this "well-illustrated" guide and "must read" for collectors of twentieth-century military memorabilia (

Antiques Diary).

Written by a longtime collector, A Guide to Wartime Collectables tells readers what to look for when looking for authentic military items. From army badges to gas masks, this book covers the major types of twentieth-century military collectables. Arthur Ward shows what these items look like and what new collectors should be looking for to ensure they're purchasing authentic artifacts and not reproductions. This book also includes photographs of the author's collection that feature important details such as insignias and other regalia.

"A very useful book written by an author who knows his stuff." — The Armourer

Written by a longtime collector, A Guide to Wartime Collectables tells readers what to look for when looking for authentic military items. From army badges to gas masks, this book covers the major types of twentieth-century military collectables. Arthur Ward shows what these items look like and what new collectors should be looking for to ensure they're purchasing authentic artifacts and not reproductions. This book also includes photographs of the author's collection that feature important details such as insignias and other regalia.

"A very useful book written by an author who knows his stuff." — The Armourer

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Guide to Wartime Collectables by Arthur Ward in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

Pen & Sword MilitaryYear

2019eBook ISBN

9781473826878Subtopic

Military & Maritime HistoryChapter 1

Insignia (Cloth and Metal)

Badge collecting has long been a popular pastime. Small, easy to store and relatively inexpensive, the myriad badges worn by soldiers, sailors and airmen have been a popular military collectable for generations. And badge collecting possesses a distinct virtue of enormous appeal to collectors as they don’t take up too much space and can be displayed or transported with ease. A badge collection is unlikely to take over a house and get you in trouble with partners or parents because it has monopolized the home.

Badges are also pretty accessible. They are the sort of thing that can be found in most general collectors’ centres, rather than one exclusively dealing with military collectables that include much larger and cumbersome items such as uniforms, edged weapons and headgear. They can often be found in the bits and pieces trays at car boot sales or in charity shops. And of course, they can now be readily bought off the internet via auction sites and specialized dealers. Because they are usually quite small, badges don’t weigh very much and this therefore keeps postage costs to a minimum. The many virtues of badges make them a natural starting point for many a militaria collector.

Although regiments first began to be numbered long ago, insignia in the modern sense was not fully adopted by armies until well into the latter half of the eighteenth century. During this period in Britain, for example, the elaborate tarleton and peaked turbans worn began to be adorned with metal badges identifying differing units. Shakos, tall cylindrical headdresses copied from the Austrians, who had in turn copied the design from Hungarian Magyars, were introduced in 1800. These 8-inch-tall ‘stovepipes’ featured large plates depicting unit insignia and were adorned with plumes denoting regular, light or grenadier companies. They quickly replaced the surviving mitres and tricorns. Headdress was supplemented by gorgets, a reminder of the days of armour. Officers wore these around the throat to denote regiment and rank and to indicate that the wearer was on duty. It was not until 1830 that gorgets ceased to be worn in the British Army. Pewter buttons featuring the particular numbers of individual regiments acted as an indication of service too. This period also saw the introduction of devices such as shoulder boards to identify rank. Previously status was only identifiable by the quality and cut of the uniform or type and prestige of weapons – either of which would have identified officer rank.

Cap badge of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry (KSLI), a regiment formed in 1881 but with antecedents dating back to 1755. In 1968 the KSLI was amalgamated with the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, the Somerset and Cornwall Light Infantry and the Durham Light Infantry, becoming the Light Infantry. In February 2007 the Light Infantry itself became part of a new regiment, The Rifles.

Buffs helmet plate. The kind of insignia worn by British soldiers from 1881–1914.

Army badges might not be as cheap as they once were but they are still affordable. British Army insignia is at the core of my collection. Although at the time of writing (October 2012) the Army is contracting, with the Daily Mail saying: ‘Cutbacks shrink the Army to smallest size since Crimean War…. The latest round of redundancies will see it shrink to about 97,000, its smallest size since the conflict in 1853. Its official strength in April last year was 101,300.’ These dramatic cuts have resulted in a very few so-called ‘super regiments’ and made it a great time to collect the badges of the many, once proud regiments who have been amalgamated. It’s a time to get them before they’ve gone, as they say. There is a finite supply of surviving Buffs, Highland Cyclist Battalion, Ox & Bucks Light Infantry and Connaught Rangers cap badges but with the imminence of the centenary commemorations of the First World War expect the existing supply to greatly diminish.

By the nineteenth century everything had become systemized to the extent that the concept of individual units being identified by name and number, and individual soldiery by standardized emblems of rank and arm of services, was internationally accepted. British armies were different from those of other nations in one important respect. Since Edward Cardwell’s reforms of 1868 Britain was the only country that had concentrated on establishing very precise regional bonds rather than just an association with a regimental number within the organization of its soldiery. Consequently, elaborate heraldic – often rather parochial – identities were adopted to denote provincial loyalties. Most other countries organized their military units solely based on less emotive and rather more impersonal numerical systems of unit classification.

RAF King’s Crown cap badge. Fortunately it is quite easy for even the novice collector to tell how old a badge is. The twentieth century quite neatly, well almost, divides in half between the time a male was on the throne and the reign of our current, female, monarch. King Edward VII ascended the throne in 1901 and Queen Elizabeth II succeeded her father, George VI, in 1952.

The Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment) cap badge. Worn on the racoon skin headdress adopted by fusilier regiments after 1901 (King’s Crown, brass).

White metal badge of the Northumberland Fusiliers: 20th, 21st, 22nd and 29th battalions (Tyneside Scottish). WWI (1914–18).

Queen’s Crown RAF cap badge. It pays to memorize the difference in design of each crown.

In 1881, when the reforms of Secretary of State for War, Hugh Childers, came into effect, the numbering system for regiments was completely discontinued and county affiliations continued to be strengthened. Most of the single battalion regiments were combined into two-battalion regiments with, for the most part, county names in their titles. This created a force of sixty-nine Line Infantry regiments – forty-eight English, ten Scottish, eight Irish, and three Welsh. The British soon discovered that men fought with vigour if they were part of the Gloucesters, Wessex Regiment or East Kents and not simply identified as the ‘4th Regt of Infantry of the Line’. The 1880s also saw the British Army adopt cloth helmets that remained in service until 1914. Because the older shako plates were unsuitable and the recent reforms had encouraged territorial titles to replace regimental numbers, new eight-pointed helmet plates – forerunners of twentieth-century cap badges – were designed for the new headgear.

Despite all these introductions, as late as 1913, the Household Cavalry for example, was distinguished by its uniform and was without a cap badge. The issue of khaki uniforms to cavalry regiments that year made the provision of cap badges a necessity and so a bronze cap badge was issued to them too. Perhaps the most famous Secretary of State for War was Lord Haldane. His reforms of 1907–1908 saw the creation of the Imperial General Staff and under his direction the British Army accommodated the necessary changes in war-fighting forced upon it by the introduction of the quick-firing bolt-action rifle and the earliest automatic weapons. Combined with use of camouflage, Haldane’s reforms encouraged the development of ‘fire and movement’ techniques and the introduction of lessons learned from Boer commandos during the South African War. Even the wide-brimmed slouch hats employed by the Afrikaans irregulars quickly found their place in British Army stores.

A broad selection of British WWII cloth insignia, including qualification, unit and field service emblems. Shown: parachute wings and ‘parachute-trained’ badge; tank crewman; machine gunner; motorcyclist; the crossed swords of a PTI (physical training instructor); 5th AA Division; printed 43 Wessex flash; grey and yellow embroidered Army Catering Corps field service strip and a set of three embroidered red infantry seniority strips.

The introduction of khaki uniforms and shrapnel helmets necessitated the introduction of battle patches. With no insignia on helmets and shoulder titles being indistinguishable at distance, these cloth devices readily identified battalions or brigades within a division. They thus enabled commanders to make battlefield dispositions without the need to be present amongst the front-line fighting. For the first time, senior army officers could lead their men into battle from the secure locations far behind the front. While the British clung on to county designations, the armies of Germany and France had long used a more impersonal system of numbers to identify individual regiments. The Germans also employed a system of colour piping (Waffenfarbe) on collars and shoulder boards to denote arm of service. In Britain at the end of the First World War it was decided that the majority of the enormous variety of insignia that had crept back onto combat uniforms – some of it distinctly unofficial – should be removed to smarten things up and, literally, get soldiers wearing uniform outfits. Thus, the new British battledress pattern introduced in 1939 was designed with homogenous simplicity in mind. This new uniform, inspired by both science fiction and the favoured choices of international tank crews then seen as the dashing twentieth-century cavalry, consisted of a stylish blouson and pleated, baggy trousers, and was designed to better suit soldiers for the new technological age. It was also considered an important aspect of field security that if a soldier was captured, this new uniform, sporting no markings other than slip-on shoulder boards that could be easily removed, wouldn’t reveal his unit and therefore the dispositions of Allied troops. Black or green buttons were also introduced to replace the previous polished brass ones. Despite the designers’ good intentions, by the end of 1940 the purpose and spirit of these new uniforms was somewhat undermined by the adoption of visible, coloured, field-service flashes. By 1941 this adornment had been augmented by the adop...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Insignia (Cloth and Metal)

- Chapter 2: Uniforms

- Chapter 3: Military Equipment

- Chapter 4: Headgear

- Chapter 5: The Home Front

- Chapter 6: Printed Material and Ephemera

- Chapter 7: Detecting Fakes and Caring for your Collection

- Chapter 8: Making the Most of Your Hobby