![]()

Part One

Rethinking Corporate Patronage

![]()

1

Corporate Patronage at the Crossroads: Situating Diego Rivera’s “Rockefeller Mural” Then and Now

Mary K. Coffey

Within the art world, the discipline of Art History, arts policy circles, art journalism, and even Hollywood filmmaking, the fate of Diego Rivera’s “Rockefeller Mural”1 at the hands of John D. Rockefeller Jr. and the Todd, Robertson, and Todd Engineering Corporation is legendary (Figure 1.1, Color Plate 2). Nearly any account of public art scandals or the perils of a capitalist art market for contemporary artists evokes the destruction of Rivera’s mural at Rockefeller Center in 1934 as a foundational episode in the modern history of art censorship and corporate arts patronage. So renowned is this episode that it helped to familiarize the more obscure story of Marc Blitzstein’s scuttled play, The Cradle Will Rock, as a consequence of political attacks on the New Deal Federal Theater Project in Tim Robbins’s 1990 film, Cradle Will Rock.

Figure 1.1 Diego Rivera, Man at the Crossroads, 1934. Fresco. Museum Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City. Photo by Bob Schalkwijk. © 2018 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

As that film draws to a close, Robbins moves between the wildcat staging of Blitzstein’s socialist play, a mock funeral procession up Broadway for a Vaudevillian’s ventriloquist dummy, and the destruction of Rivera’s mural. Large chunks of frescoed plaster fall from the wall as the procession mournfully proceeds uptown, all to the heroic strains of Blitzstein’s Brechtian libretto of working-class solidarity. At the end of the film, only a fragment of the mural survives—an image of a venereal disease microbe—clinging to the wall as an emblem of corporate blight. The close-up of the fragment slowly fades back to Broadway, as the 1930s mise-en-scène gives way to a view of today’s Times Square, filled with the gaudy visual extravaganza of commercial entertainment on steroids. Robbins’s point is clear, market-based arts patronage is a disease that constrains artistic freedom and converts visual culture into a commodity fetish that has no capacity for social uplift, let alone enacting progressive change.2

While this story is well known, my purpose here is to revisit it within the specific context of contemporary corporate art patronage, to assess whether or not the Rockefellers and their management team were prototypical patrons of this sort, and to determine what, if anything, the commission and destruction of Rivera’s mural illuminates about the privatization of culture today. While wealthy elites have been patrons of art since the emergence of market-based systems of patronage in the early modern period, today’s corporate art patronage is typically understood as a result of changes in the federal subsidization of art that began in the 1980s.3 Prior to the Reagan-era push to shift the bulk of cultural funding from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) to the private sector, numerous private foundations and nonprofit organizations existed.4 Likewise, as the Rockefeller Center episode makes clear, corporate patronage, while less prevalent than private philanthropy, has existed in the United States since at least the turn of the latter half of the nineteenth century (consider the Railroad Companies’ patronage of western landscapes).5 In fact, following Alan Trachtenberg’s arguments in The Incorporation of America, the corporatization of all sorts of enterprise, not just arts funding ones, was a defining feature of the Gilded Age.6

Nonetheless, since the 1980s there has been an exponential boom in corporate collecting, corporate sponsorship of cultural events, and corporate patronage as handmaiden to real estate development. Due in part to changes in the tax code as well as new marketing logics that view cultural capital as an integral part of a “cause related” branding strategy,7 the “intervention,” to use Chin-tao Wu’s term, of corporations in the art world is typically viewed as a deformation of the cultural landscape. On the one hand, it has led to the encouragement and privileging of market-friendly aesthetics over and against controversial or less commodifiable forms of art. For critics, the worry is that this taste culture constrains artists and limits consumer choice. On the other hand, concerns about the conversion of cultural capital into economic capital, and vice versa, through corporate art patronage have lead critics to wonder about the way that a company’s marketplace advantage can be leveraged not only in social and cultural life but also in political decision-making.8 Related to these concerns are worries about the collaboration between artists and the interests of big business, as some appear to embrace the subordination of their work to commercial agendas, as witnessed, for example, in the participation of artists in high-profile corporate advertising campaigns. Critics worry that this commercial art ethos has supplanted the oppositional ethics of the avant-garde. And certainly, the controversy over Diego Rivera’s mural at Rockefeller Center pinpoints the historical moment when the relationship between artists and private (as well as federal) patrons became vexed as a consequence of an emergent avant-garde ethos (bolstered by an affiliation with socialism) among American artists that often ran counter to the capitalist or conciliatory goals of their funders.9 These concerns raise the following questions with regard to the Rockefeller incident: What was the nature of corporate patronage in the 1930s? If John D. Jr.’s “private interests,” to quote Catha Paquette, determined the commission and destruction of the work, what were those “private interests” and do they prevail today within the corporate sector?10

To begin, we need first to review the general facts of the Rockefeller Center case, which, despite a few disagreements between scholars, have achieved the status of consensus within the extant literature.11 In January 1932, several years into the massive development of Rockefeller Center,12 Diego Rivera was having lunch at the townhouse of Abby Rockefeller along with her son, Nelson, and her friend and art advisor Frances Flynn Paine, among others. Rivera and his wife Frida Kahlo had been frequent guests of the Rockefellers since Rivera’s one-man show at the newly established Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) earlier in 1931. While at that lunch, the topic of a mural in the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) tower came up, and Abby suggested Rivera for the commission. John R. Todd had already been at work attempting to secure Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse for the commission, but had failed. So when Nelson brought Abby’s suggestion to his father, John D. recognized that Rivera, while not an artist he “personally cared for,” might indeed be a “good drawing card.”13

With John D., the Todd, Robertson, and Todd management team, and the architect Raymond Hood on board, Rivera secured the commission, but not before he had renegotiated the terms to allow for the use of a full-color palette (as opposed to painting in a monochromatic one) and true fresco (rather than painting on canvas that would then be glued to the wall).14 He would receive $21,000 for the mural, $7,000 when he began and the remaining $14,000 as severance pay when he was dismissed from the project.15 This money covered not only the artist’s labor but also his expenses and the salaries of his assistants. In exchange for this sum, Rivera signed a standard contract agreeing that, upon final payment, the mural would be owned by Rockefeller Center and that its managers would determine whether or not the work was on view.16

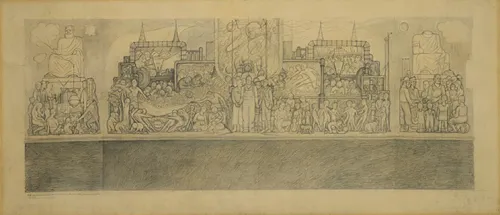

While still completing his cycle at the Detroit Institute of Arts, Rivera began working out his interpretation of his patrons’ ponderous theme, “Man at the Crossroads Looking with Hope and High Vision Toward the Choosing of a New and Better Future.” And by November of that year, he had submitted a preliminary sketch and a statement of his intentions to both Nelson and Abby (Figure 1.2). The verbal description made Rivera’s Leftist orientation clear to anyone familiar with the language of Marxism. “My panel will show the Workers arriving at a true understanding of their rights regarding the means of production,” he wrote.17

Figure 1.2 Diego Rivera, Man at the Crossroads, 1932. Pencil on paper, 31 × 71 ¼ inches. MoMA, New York. Anonymous Gift. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY. © 2018 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D.F./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

The sketch was less pointed, although anyone schooled in the iconography of the Left would have been able to discern Rivera’s point. It centered on a worker in blue overalls holding hands with a peasant and a soldier, a motif that appears multiple times in his Ministry of Public Education cycle (1923–28) in Mexico City, in which he openly espouses proletarian revolution, and where he had specifically taken aim at American robber barons in Wall Street Banquet, a panel that includes an unflattering caricature of John D. Rockefeller Sr.18 To the worker’s right (viewer’s left) are scenes of social unrest, including children playing tug of war and a television screen that depicts gas-masked soldiers. To his left (viewer’s right) are scenes of social cooperation. Here the television screen shows a robust worker’s celebration taking place before a ziggurat-like structure that resembles Lenin’s Tomb in Moscow’s Red Square. Despite Rivera’s reputation as a communist propagandist, and these early indications of his intentions, the sketch and concept were approved by Raymond Hood shortly thereafter. By early 1933, Rivera was at work on an enormous scaffold (that obscured much of the evolving imagery), painting night and day before crowds of ticketed onlookers to make the May 1 deadline for the inauguration of the mural and building.19

Rivera’s mural was to have covered three sides of the enormous elevator vestibule in the grand lobby at the 5th Avenue entrance. The main wall alone was 63 feet wide and 17 feet high. While the mural was always structured by a contrast between capitalism and socialism, with the worker at center poised to “choose” between them, the iconographic details of the central panel, in particular, underwent major revision as Rivera worked. He sidelined the triumvirate of worker, peasant, and soldier, and focused instead on the worker, now depicted at the helm of an enormous machine (the eponymous “Man at the Crossroads”) (Color Plate 2). This change was likely a consequence of Rivera’s general shift away from the immediate concerns of post-Revolutionary Mexico as a consequence of his encounter with US industry and labor politics. While modernization had always been a cornerstone of his vulgar Marxism, once in the United States, he became fascinated with modern industry and its capacity to both liberate and enslave humanity.20 This theme is most famously explored in his Detroit Industry mural (1931–32) where he lionized Henry Ford’s River Rouge factory while also expressing doubts about the technocratic management of life under capitalism.21

In front of the worker Rivera depicted two crossed ellipses, one detailing the biological world of the microcosm—disease microbes, cell-division, the fertilization of an egg alongside a developing fetus—and the other, ...