![]()

Chapter 1

The Invention of War

War is the legacy that the ancient world bequeathed to the modern one. There is little evidence of war before the emergence of the world’s first complex human societies. War is a social invention that required specific conditions to bring about. But because war has been omnipresent from the very beginning of man’s recorded history, about 3500 BC, it is assumed by some that war must have been present even before that.1 But when war as a social institution is placed in historical perspective, it is obvious that it is among the most recent of man’s social inventions.

The first evidence of a hominid culture that used tools emerged 500,000 years ago in the Olduvai Gorge stone culture in Africa. The honour of initiating the Stone Age with the first use of tools goes to Homo erectus, our direct though not most immediate ancestor. Four hundred thousand years later, Homo sapiens and his now extinct cousin, Neanderthal man, created a more advanced stone culture with a wider range of tools, including the first long-range weapon, the spear. It is this later period that serves as a baseline from which to study the emergence of warfare. Otherwise, we would have to admit that for more than 98.8 per cent of its time on this planet, the human species lived without any evidence of war whatsoever.

Using the Stone Age cultures of Homo sapiens and Neanderthal man as a starting point, some remarkable facts emerge about the development of war. Humans required 30,000 years to learn how to use fire, and another 20,000 years to invent the fire-hardened, wooden-tipped spear; spear points came much later. Sixty thousand years later, humans invented the bow and arrow. It required another 30,000 years for humans to learn how to herd wild animals, and another 4,000 years to domesticate goats, sheep, cattle and the dog. At about the same time, there is the first evidence for the harvesting of wild grains, but it took another 2,000 years for humans to transplant wild grains to fixed campsites, and another 2,000 years to learn how to plant domesticated strains of cereal grain. It is only after these developments, around 4000 BC, that warfare made its appearance as a major human social institution.2 Seen in historical perspective, mankind has known war for only about 6 per cent of the time since the Homo sapiens Stone Age began.3

Once warfare became established, however, it is difficult to find any other social institution that developed as quickly. In less than 1,000 years, humans brought forth the sword, sling, dagger, mace, bronze and copper weapons, as well as fortified towns. The next 1,000 years saw the emergence of iron weapons, the chariot, the standing professional army, military academies, general staffs, military training, permanent arms industries, written texts on tactics, military procurement, logistics systems, conscription and military pay. By 2000 BC, war had become an important social institution in all major cultures of the world.4

War is properly defined as a level of organized conflict involving forces of significant size rooted in the larger society’s organizational structure, applying a killing technology with some degree of organization and expertise. War also requires the systematic, organized societal application of orchestrated violence on a significant scale.5 Without these conditions, one might find murder, small-scale scuffles, raids, ambushes, executions and even cannibalism, but not war.6 Accordingly, for the first 95,000 years after the Homo sapiens Stone Age began, there is only limited evidence that humans engaged in organized conflict on any level, let alone one requiring organized group violence.7

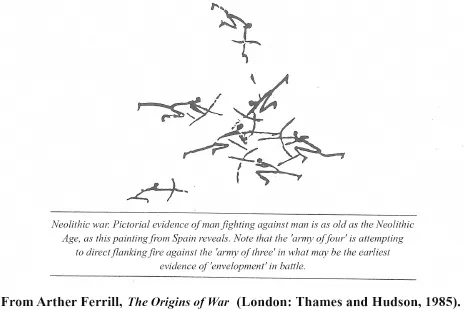

The first evidence of truly organized violence on some scale occurs sometime around 6500 BC at Jebal Sahaba in the Sudan. The skeletal remains of fifty-nine people, including women and children, suggest that they were killed by repeated arrow wounds and spear thrusts.8 It is unclear if these people were killed in a raid or ambush, or simply executed. About half the skeletons had arrow points embedded in them, and it appears that the bodies may have been deposited in smaller groups over time. What is certain is that an organized force of some size was necessary to carry out the killing. A Neolithic site in the Transcaucasus reveals the first rock painting of the period that seems to show a small armed squad attacking and killing other men with bows and arrows. While it required another 1500 years for humans to reach a level of organized violence that could be unequivocally identified as war, it seems clear that by 6000 BC humans had already learned to use organized groups to kill other humans. Still, for most of the Stone Age humans lived without even small-scale organization for killing other humans. This is hardly surprising considering how humans lived for all but the last few hundred years of the period.

Figure 1: Neolithic Rock Painting

For all but the last 10,000 years, humans lived as hunter-gathers organized into small groups of twenty to fifty people. Most of the members of these groups were related by blood or marriage, much like an extended family. These groups travelled constantly in small migratory bands following the seasonal migration of the game, and assembled as clans on a seasonal basis as the normal migration of the wild herds brought them together. It is unlikely that these clan groups had any social organization of any kind. They had certainly not yet evolved into tribes. Under these conditions, organized conflict of any sort was a rare occurrence. The small size of the groups alone would have mitigated against it. The average hunter-gatherer group had within it not more than six or seven armed adult males, and the need to hunt and feed their families would have made it impossible for them to serve primarily as warriors. The constant movement of the group also made it unlikely that they would come into contact with other groups, except on rare occasions.9 The only weapon capable of being used in war at this time was the spear, and there is no evidence that humans ever used it to kill other humans during this period.10

For humans to abandon seasonal migrations required an expansion and stability of their food supply and a more certain way to obtain migratory game. The expansion of the food supply came first. At Mureybet in Syria around 8300 BC, there appears the first archaeological evidence of the planting of wild cereals.11 Later, humans moved from harvesting wild grains to transplanting them to more stable home camps. Humans were on the threshold of creating the tribe. Mureybet appears as the first stable small village made possible by the rudimentary cultivation of cereal grains. At about the same time (8350 BC), the ‘earliest town in the world’ came into being at Jericho in Palestine, the world’s first large-scale permanent human settlement. The people of Jericho had mastered the secret of seed corn and the technology of irrigation to plant and grow it, supporting a population of about 2,500 people.12

The first evidence of humans’ ability to domesticate animals on some scale also appears around 7000 BC. Byblos offers the first evidence of the domestication of sheep, goats and cattle, and using the trained dog as a helper.13 Five hundred years later, at Catal Huyuk in Anatolia, we find the first large-scale irrigation to support agriculture. The number of dwellings within the town, about 1,000, suggests that the population of Catal Huyuk was about 6,000 people, twice the size of Jericho.14 By 5,000 BC, humans had succeeded in stabilizing and expanding their food supply to a degree that could support human groupings in the thousands, with agriculture bringing to an end the hunter-gatherer way of life that humans had known for more than 800,000 years. Large stable populations permanently tied to specific places made possible the evolution of the tribe. Tribal societies with their larger populations, adequate food supply and the corresponding de-emphasis on hunting were able to produce a class of hunters that evolved into a new class of warriors, whose claim to social role and status was based less upon their hunting prowess than their ability to fight and kill other warriors in defence of the tribe. For the first time in human experience, there arose a social group whose specific function and justification was its ability to kill other human beings.15

Once a warrior caste came into being, it would have been a matter of only a few generations before no one could remember when there had been no warriors at all. Within a short time, the new social institution would have seemed as normal a part of society as cattle herders and farmers. Once the military technology became available, these new warriors and the tribal social orders that created them were able to fight wars of much greater scope and lethality than had previously been the case. But the presence of a warrior caste by itself did not mean that it would have had to develop into an organized force for large-scale warfare. Most early war was highly ritualized, with low levels of death and injury, much as combat between other species of animals is. To move from ritualized combat to genuine killing required a change in human psychology. When and how Neolithic tribes transitioned from ritual to real warfare is unknown. What is certain, however, is that they did make the journey.

War, then, seems a social invention brought into being as a consequence of previous human social developments. Certain kinds of behaviour (war) require certain structures to initiate and sustain that behaviour. From this perspective, warfare on a large scale requires at least the following social developments: (1) a stable population of a size large enough to produce a surplus population freed from traditional economic roles to serve as a source of military manpower; (2) a territorial attachment specific enough to change the psychology of the group so that it thinks of itself as both special and singular, i.e. territoriality of some sort, ethnic, religious, land, etc.; (3) a warrior class with social influence in the decision-making process; (4) a technology of war, i.e. weapons; (5) a complex, role-differentiated social order, a political and administrative structure; (6) a larger mental vision of human activity that stimulates the generation of artificial reasons for engaging in behaviour, often religiously or culturally based.16

The late Neolithic age (6000–5000 BC) witnessed an advance in the development of new weapons that was, until then, unparalleled in human history. It was but a short time before these weapons were used in large-scale warfare. The major weapons of this period were the bow and arrow, the mace, spear, dagger and sling.17 The fire-hardened spear had been around for thousands of years. Its major improvement in the Neolithic period was the use of stone, flint and obsidian spear points. Flint and obsidian spear points require pressure-flaking when chipping the point from the larger stone. Pressure-flaking makes possible spear and arrow points that are flat on two sides, reducing weight and increasing penetration. Pressure-flaking also made possible longer one-piece blades, an innovation first applied to reaping and skinning knives before giving rise to the dagger. This new technology first appeared between 7500–6800 BC at Cayonu in Syria,18 and spread widely and rapidly throughout the Middle East.19

The dagger made an excellent short-range weapon, and as soon as man developed metals technology to increase the length of the blade, the sword followed. The mace with a stone head affixed to a wooden handle could easily cave in a man’s skull. The handle also increased the accuracy and striking momentum of the weapon when thrown. The bow had been in existence for millennia, but aside from the use of flat arrow heads, there appear to have been no improvements in its composition or strength until much later, when the Sumerians introduced the composite bow. The bow was easy to fashion and use, and could kill from a distance, capabilities which probably made it the basic killing weapon of the Neolithic warrior.

An important innovation was the sling.20 Evidence for its existence appears at Catal Huyuk between 5500–4500 BC. Here we also find the first evidence of shot made from sun-baked clay, the first human attempt to make a specific type of expendable ammunition. The sling represented a great leap in killing technology. Even an average slinger can throw shot to a range of 200 yards. Small shot can be delivered on a trajectory almost parallel with the ground over ranges of 100–200 yards, while larger stones can be fired howitzer-like over greater ranges.21 All these weapons except the sling have developmental histories that point to their original invention as weapons of the hunt. The sling may have been the first weapon designed primarily to kill humans, since its hunting function is marginal at best.

But weapons are useless without tactics to direct their employment in battle. The most basic tactics are the line and column, and the ability to approach in column and move into line. Tactics, of course, require commanders, which implies at least some rudimentary military organization. The importance of tactics in the development of war is suggested by H. Turney-High, who argues that evidence of simple tactical formations is the definitive characteristic that constitutes a ‘military horizon’ separating fighting from genuine war.22 While the Neolithic period may have witnessed the first use of tactics in fighting among humans at war, it is likely that they were originally developed long before as techniques of the hunt.

Just prior to 4000 BC, there appears the first evidence of fortified towns. The classic and much earlier example is Jericho. While other towns of the period show some degree of fortification, mostly ditches and mud walls or, as at Catal Huyuk, houses abutting one another so that the outside walls of the dwellings constitute a wall around the whole settlement, only Jericho reflects a type of architecture that would be readily recognizable as military architecture. Jericho’s walls enclosed an area of 10 acres and ran to a length of 765 yards. The walls were 10ft thick and 30ft high. A 28ft t...