- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

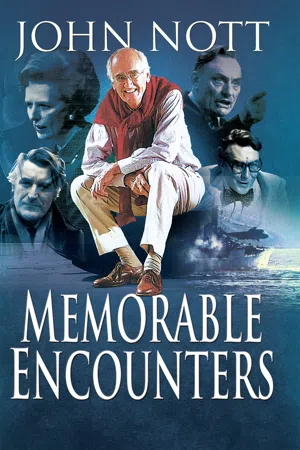

Memorable Encounters

About this book

During his varied career John Nott has encountered numerous interesting people, some household names and others well-known in their field. In Memorable Encounters he has selected twenty individuals to discuss and reflect on their contribution.

His seventeen years as an MP, latterly as a Cabinet Minister, brought him into contact with leading politicians, including Enoch Powell, Margaret Thatcher and Norman Tebbit. While Defence Secretary during the Falklands War he worked closely with Admiral Lewin and General Bramall. As a young officer he served with the 2nd Gurkhas and, through a profile of Humbahadur Thapa, he describes his experiences with these stalwart soldiers.

Nott’s principal career was in the City and he describes the role Siegmund Warburg played in his life.

To add variety and spice, the Author includes personalities whom he came across during his education, farming in Cornwall and pursuing his interest in fishing. Additionally he describes his friendship with impressive characters including Ted Hughes, the Poet Laureate, and Martin Rees, the Astronomer Royal. Robin Day, whose interview he famously walked out of, features as does Nigel Farage.

The book is dedicated to Miloska, his wife, whose story is worthy of a work of its own.

All these characters and more make Memorable Encounters an unforgettable read.

His seventeen years as an MP, latterly as a Cabinet Minister, brought him into contact with leading politicians, including Enoch Powell, Margaret Thatcher and Norman Tebbit. While Defence Secretary during the Falklands War he worked closely with Admiral Lewin and General Bramall. As a young officer he served with the 2nd Gurkhas and, through a profile of Humbahadur Thapa, he describes his experiences with these stalwart soldiers.

Nott’s principal career was in the City and he describes the role Siegmund Warburg played in his life.

To add variety and spice, the Author includes personalities whom he came across during his education, farming in Cornwall and pursuing his interest in fishing. Additionally he describes his friendship with impressive characters including Ted Hughes, the Poet Laureate, and Martin Rees, the Astronomer Royal. Robin Day, whose interview he famously walked out of, features as does Nigel Farage.

The book is dedicated to Miloska, his wife, whose story is worthy of a work of its own.

All these characters and more make Memorable Encounters an unforgettable read.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Enoch Powell

Politician

I was one of the congregation awaiting the arrival of Enoch Powell’s coffin at his funeral in St Margaret’s Westminster when my neighbour, Ronnie Grierson, whom I had known in the City firm of Warburg, said in a loud whisper, startling our surrounding mourners, ‘I suppose you know, he is being buried in his uniform.’ As the bearers moved down the aisle a respectful silence fell upon the crowded congregation. Powell had been a controversial figure right up until his death, mainly as a result of one foolish speech.

After the funeral Powell’s body was taken up to Warwick where he was indeed buried in his brigadier’s uniform among the soldiers of the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in which he had served, initially as a private soldier. He was really rather a strange man: when asked in April 1986 what he would like to be remembered for, he replied, ‘I would like to have been killed in the war.’

He was the son of elementary school teachers, and his mother, who was the most important influence in his life, was the daughter of a policeman. The family, from Nonconformist stock in Wales, was ambitious and concerned with self-improvement.

Enoch won a scholarship to King Edward’s School in Birmingham, which he entered in 1928 at the age of thirteen. There he was remembered as a loner and this fixed his character for the rest of his life. He was austere and did not make friends easily. Indeed, he was given the nickname ‘Scowly Powelly’, and a contemporary said of him, ‘He could not smile and had a crocodile face of such ferocity that even the naughtiest boys were not prepared to tease him.’ He was two years ahead of his contemporaries in study and when he took the Higher School Certificate, the equivalent of A-levels, he went into the examination having memorized in Greek the whole of St Paul’s Epistle to the Galatians.

When he took the scholarship exam in Classics to Trinity College, Cambridge, he left the exam halfway through the allocated time and did two version of the same piece, one in the style of Thucydides and another in the style of Herodotus. At Trinity the Master of his college invited him to tea with other freshmen and, uniquely, he refused, saying, ‘Thank you very much, but I came here to work.’ By all reports he sat in his unheated room in an overcoat with a blanket across his knees working at the Classics. When he travelled – he was a traveller all his life – he often slept in Cambridge railway station. He set a standard for reclusiveness, politely refusing invitations because they interfered with his studies.

In 1931 he first met the poet A. E. Housman, then Kennedy Professor of Latin, on a staircase in Trinity; the author of ‘A Shropshire Lad’, Housman became Enoch’s hero, but the friendship took years to develop. To an extent Powell modelled himself on Housman. He read and eventually wrote poetry with the same intensity. Neither Powell nor Housman was able to communicate easily with the outside world.

In 1934 Powell was elected a fellow of Trinity, specializing in the works of Thucydides and Herodotus, but he described himself as ‘suffocating’ in the enclosed world of the college. Every time he walked through its Great Gate, he said, ‘[I] felt that I was going out of this world into something enclosed and all my instincts were to get out of what was enclosed in this world.’ I felt the same myself as an undergraduate at Trinity.

In due course he accepted an appointment as Professor of Greek at Sydney University, where in the 1930s he developed increasing frustration and anger at the appeasement of Hitler and saw Munich as a disgrace. He went around saying, ‘We want war’, which must have surprised Australians on the other side of the world. It was at this time that he developed an obsession about being killed. He wanted to die in the front line, but this privilege was always denied him; he was to become the most senior intelligence officer in India, and then the youngest brigadier in the British Army.

In the years immediately before the outbreak of the war he returned to Europe, spending time in Germany, where he was briefly arrested by the Gestapo. He spoke German fluently (as well as six other languages) and was a passionate follower of Nietzsche. He then went on to Russia, learned Russian, and came to believe that Britain’s long-term future lay in an alliance with Russia against the Americans. His dislike and suspicion of America and the Americans, which he maintained quite discreetly all his life, was one of the few prejudices he shared with Edward Heath.

That brings me back to Enoch’s funeral. He was intensely proud of having been recruited into the Royal Warwickshire Regiment as a private soldier. He only managed this, at a time in the Phoney War in 1940, by posing as a Commonwealth citizen from Australia. He said that the most honourable and testing promotion that he ever received in life was from private to lance corporal.

In India during the war, as a brigadier in intelligence, his requests to join the front line in Burma being always denied, he prepared the plan for the country’s defence in post-war days. In fulfilment of this task he travelled all over India and developed a great passion for the Raj. He fell deeply in love with India and the Indians, so much so that he developed an ambition to become Viceroy, one he realized could only be achieved through the English political system.

As may be imagined, he pored over that outstanding novel A Passage to India by E. M. Forster and said, after Attlee had agreed to Indian independence – the idea of which horrified him – ‘The dream that the British and the Indians dreamed together for so long, a dream unique in human history in its strangeness and improbability, was bound to break one day. Even India, the land of hallucinations, could not preserve it forever from its contradictions.’

This was Enoch at his emotional best, expressing his sorrow at the ways of politics; in spite of his set of strong beliefs and principles, he was always prepared to accept the inevitability of change and the need for adaptability.

On demobilization, Enoch found his way into politics with the future of India at the forefront of his mind. The story goes that an official once told Winston Churchill that he might like to read Brigadier Powell’s report on the recovery and defence of India. Churchill is said to have replied that he did not have the time to see that ‘madman’, and, indeed, the sense among the Macmillan generation that somehow Powell was mad was prevalent. He was always lecturing his colleagues with views, particularly on economic issues, which were outside the accepted conventions of the time.

Although I never came to understand Enoch, I share his view that soldiering and politics are the two professions that all men should aspire to. By soldiering Enoch was thinking of the life of a private soldier not a general; and in politics, of a parliamentarian not a Minister. Although he admitted that he would like to hold high office one day, he was happy with the freedom of the backbenches which gave him untrammelled scope to explore the intellectual and practical limits of parliamentary democracy – and this is where his gift to our country’s economic policy is so profound. ‘I do not deny’, he said, ‘that I would like to have been Secretary of State for Defence, but that would have been at the price of renouncing my freedom to speak my mind on matters which seemed to me to be of transcending interest and importance.’

There were two reasons why I got to know Enoch rather better than most other parliamentary colleagues. He was always, of course, a brooding presence during my time as Economic Secretary in the Treasury. I often suffered from his biting tongue, particularly during the Heath government. I was the poor sod who day after day found himself defending Heath’s economic policy in the House of Commons. I did not believe in it, but I saw no purpose in resigning. When Enoch had left the Conservative Party for the Ulster Unionists he gave me an easy time in Parliament throughout the Falklands campaign – and he supported my Defence Review in 1982.

But more particularly, I was one of the younger members of the One Nation Dining Club, which met weekly in the House of Commons to discuss topical, mainly economic, issues. Heath dropped out when he became leader of the Conservative Party, but other members of the Macmillan generation like Reginald Maudling, Robert Carr, Sir Keith Joseph, Iain Macleod and Enoch were regular attendees. There was a philosophical gulf between the Macmillanism, represented especially by Carr and Maudling, and the younger entrants to Parliament in 1964–6 who were seeking a complete break from Macmillan’s paternalist, collectivist consensus and the ‘politics of decline’. The weekly arguments, with Enoch mainly against the rest, were fascinating for a new member like myself.

The more important and instructive gathering was under the auspices of the Economic Dining Group. This was founded by Nicholas Ridley and John Biffen, two of Enoch’s admirers: the idea was to try and anchor Powell in the Conservative Party. Ever since Heath had forced through the European Communities Act, Enoch had been threatening to leave the Conservative Party, which he did in 1974. Thereafter he came back to Parliament – but as an Ulster Unionist.

The meetings of the Economic Dining Club took place once a month in members’ houses. The other members, apart from Ridley and Biffen, were John Eden, Jock Bruce-Gardyne, Michael Allison, Peter Hordern and Cranley Onslow. We had a debate about inviting new members, and Margaret Thatcher, who was leading the Opposition Treasury team in Parliament, was suggested, but she was vetoed ‘because she talks too much’. When she became leader of the Party, she joined us and was an assiduous attendee each month. There, under a dominating Enoch Powell, we thrashed out the economic issues of the day – and due to Enoch more than any other person, what came to be known as Thatcherism saw its birth in our discussions.

Every issue discussed led to a forceful intervention by Enoch, who fastened on any inconsistency or flaw in other people’s arguments. But he did so always, even in private society, with blazing eyes and a thin smile. My wife, busy serving the meal on one occasion, said something about ‘principles’. ‘Principle, principle, principle,’ said Enoch in a questioning way. To this day, we ponder what he meant, because he himself was a man of principle.

I remember an occasion when Hector Laing, who was a well-known establishment figure, chairman of his biscuit empire and a close friend of Margaret Thatcher, came to a meeting of Conservative backbenchers. He was appointed to the Court of the Bank of England. Clutching a prepared speech, he began, ‘The days of unfettered capitalism are over …’ These were the only words he had uttered, before Enoch, who was sitting in the front row, immediately stood up and shouted, ‘Stick to biscuits’, before walking out of the room and slamming the door as he went. The speed of Enoch’s reaction was highly entertaining, but not for Sir Hector, I suppose.

One evening we dined in some private club and the discussion went on very late. We found the exit door locked and had to climb out along a balcony and over a drainpipe. Nick Ridley’s memoir captures the picture of Enoch climbing down the drainpipe in his blue overcoat and Homburg hat.

Enoch’s was the most influential intellect of my generation. He certainly created the concept of Thatcherite economics which was adopted by Keith Joseph, Thatcher herself, and later followed by Tony Blair and succeeding governments. At the heart of his belief was the inviolability of markets – and in particular the price mechanism. In a democracy he believed that it was only through the price mechanisms that competing demands can be reconciled: ‘To my own satisfaction I reached the conclusion that the price mechanism is one of the means by which a society takes certain collective decisions in a manner not necessarily ideal but in a manner which is manageable and acceptable and broadly speaking is regarded as workable, a mechanism which cannot safely or wisely be replaced by conscious formulation and by compulsion.’ He believed that the early action of the first Thatcher government to abolish price and incomes legislation – and abolish exchange control – was the start back from Macmillan tri-partisanship and indicative planning on the French model so much admired by Edward Heath, Carr, Maudling and others.

Heath endorsed a memorandum to him as Prime Minister by Reginald Maudling which read:

The job of the Treasury is to use the instruments at its command to make the real economy grow faster, thereby bringing down unemployment and delivering real wage increases, workers will restrain their real wage demands, and as they restore their share of rising output, inflation will fall.

Economists at this time talked about the ‘real wage push theory’; it was utter nonsense and led to what was described as the ‘Barber boom’, the loss of the 1974 election and the chaos faced by the Callaghan administration, which tried but failed to keep the trades unions under proper control. The only way to discipline the trades unions was by means of monetary policy, adopted by the incoming Thatcher government.

In contrast to the Macmillan consensus and tri-partisanship I have to include a speech made by Enoch Powell at the Conservative Party conference in Brighton in 1964. It set out succinctly what to me is the foundation of all good economic policy making.

There is no secret about the cause of the ‘cycle of stagnation, restriction and debt’. For a quarter-century we have been taught to believe that our livelihood depends on a pretence, on pretending that a £ is worth more in the world than it is. So we cling desperately to a fixed exchange. But so long as the price of anything is fixed, it will nearly always be wrong: for everything in the real world is changing all the time. The result has been either a surplus or a deficit and increasingly often a deficit. So we borrowed huge sums to keep up the fiction and accepted government interference in our lives in all directions. Once you have a wrong price fixed for anything, there is no interference by government that cannot be justified.

This being the cause, the remedy is plain. We have to do what we were on the verge of doing after 1951 but unhappily did not. We have to set the rate for the pound free to behave like any other price and keep supply and demand in balance. A fortnight ago this would have sounded like theory. For ten days now it has been fact. The pound has been floated, at least against the mark and, contrary to expectation, the world has not come to an end …

The truth is better, the truth is safer; and the truth is freer. In this, as in so much besides today, our fears are our own worst enemy. Let us dare to face reality: it is the road to freedom.

Just think about it. In all those post-war years one government after another supported a fixed exchange rate for the pound. Devaluation became the number one dirty word in politics in spite of the fact that it became necessary in one exchange rate crisis after another. Every month the Treasury published the balance of payments statistics – and did its Treasury best to cook the figures. Yet the balance of payments didn’t matter – what mattered was the price of the pound against other currencies.

I was involved in a great run on the pound in 1974 – although perhaps John Major’s government suffered an equal humiliation for the country when it clung to a fixed rate in the ERM, losing billions across the exchanges. In 1974, it became impossible to hold the fixed rate of exchange. Tony Barber, the Chancellor, Ted Heath, myself as Economic Secretary and Treasury officials met in the Prime Minister’s room in the House of Commons. Ted Heath, with his fixation on being a good member of the European club, was a great supporter of holding currencies fixed together, in a need for stability and as a step towards European Monetary Union. I give Heath full marks that he saw that, against all his instincts, the only way out was to float the pound, not devalue it. We did so, and, subject only to Major’s incompetence with a fixed rate through the ERM a few years later, we have been floating ever since.

I don’t want this sketch of Enoch Powell to descend into an economic seminar – that would be tedious for most readers – but I have to applaud Enoch’s gift to our country: sanity in appreciating the essential nature of the price mechanism, only possible in free markets. We should remember three fundamental strategic facts. First, that the Americans could never have humiliated this country at Suez if we had been the possessors of a floating pound; the fixed rate of sterling enabled Macmillan, as Chancellor, to rat on his colleagues and force our surrender at Suez. Second, my belief that we could not have carried out the Falklands campaign had we been operating under a fixed rate of exchange; and third, that the collapse of the European Union is inevitable if it persists in the single currency, driving southern Europe into increasing poverty and unemployment; we could not possibly be part of it.

As I write, the Europe debate continues, following the Referendum, like ‘weeds through concrete’, to quote an Enoch phrase. In a sense he was a British Gaullist favouring a partnership of nation states. Enoch’s principled opposition to the Rome Treaty led him to abandon the Conservatives for Labour in the 1974 election. Powell had long argued, some would say with keen judgement, that the logic of the Rome Treaty, for better or worse, would compel centralism. He could not believe or accept that the British Parliament would ever forego its right to make its own laws, be subject to a European court of justice and defer to a foreign bureaucracy based in Brussels. It was inconceivable to him that British patriots could ever relinquish their rights to govern themselves. The weeds are certainly coming through the concrete today as we negotiate our exit from the European Union which still dreams of centralism and control. Heath managed to force the European Communities Act through Parliament on a guillotine motion with a majority of seven. We never entered the Common Market with the full heartfelt consent of the British people.

It is inevitable that I finish with the ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in Birmingham in April 1968. Tony Blair will only be remembered for Iraq, Major for the currency crisis as we were forced out of the ERM, Cameron for his Referendum and Enoch for his Birmingham speech on immigration. It is all very unfair, but that is politics.

Enoch’s speech caused considerable distress among his friends, including John Biffen. The violence of his language was a great mistake. Ted Heath was right to dismiss him from the Shadow Cabinet. Powell himself excused it, just, saying that he should have emphasized the quotation marks a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One: Rt Hon. Enoch Powell MBE– Politician

- Chapter Two: Sir Siegmund Warburg– Banker

- Chapter Three: Lord Lewin KG, GCB, LVO, DSC– Admiral of the Fleet

- Chapter Four: INGA– Berlin 1951

- Chapter Five: Lord Tebbit CH– Politician

- Chapter Six: Lord Rees OM, FRS– Scientist, Astronomer Royal

- Chapter Seven: Sir Robin Day– Broadcaster

- Chapter Eight: Major Humbahadur Thapa MVO– Gurkha soldier

- Chapter Nine: Michael Charleston OBE– Journalist and fisherman

- Chapter Ten: Ted Hughes OM, OBE– Poet Laureate

- Chapter Eleven: Lord Heseltine CH– Politician

- Chapter Twelve:Billy Collins– Cornish farmer

- Chapter Thirteen:Miloska– Lady Nott OBE

- Chapter Fourteen: Margaret Thatcher LG, OM, FRS– Prime Minister

- Chapter Fifteen: Douglas Shilcock– Prep school headmaster

- Chapter Sixteen: Professor Sir David Omand GCB– Civil servant

- Chapter Seventeen: Sir Ian Fraser CBE, MC– Soldier, journalist, banker

- Chapter Eighteen: Lord Hurd CH, CBE– Politician

- Chapter Nineteen: Lord Bramall KG, GCB, OBE, MC– Field Marshal

- Chapter Twenty: Nigel Farage– Politician, broadcaster

- Postscript

- Acknowledgements

- Plate section

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Memorable Encounters by John Nott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.