- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

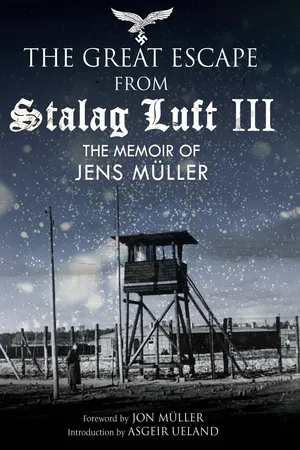

The true story behind the real "Great Escape" from a World War II Nazi POW camp by the veteran Norwegian pilot who lived it.

Jens Müller was one of only three men who successfully escaped from Stalag Luft III (now in Poland) in March, 1944—the break that later became the basis for the famous film The Great Escape. Together with Per Bergsland, another Norwegian POW, he stowed away on a ship to Gothenburg, Sweden. The escapees sought out the British consulate and were flown from Stockholm to Scotland. From there they were sent by train to London and shortly afterwards to "Little Norway" in Canada.

Müller's book about his wartime experiences was first published in Norwegian in 1946 titled Tre kom Tilbake (Three Came Back). This new edition is the first English translation and will correct the impression—set by the film—that the men who escaped successfully were American and Australian. In a vivid informative memoir, Müller details what life in the camp was like and how the escapes were planned and executed, and tells the story of his personal breakout and success reaching RAF Leuchars in Scotland.

" The Great Escape from Stalag Luft III offers a fascinating look at the 1940s, recapturing the feel of both the war and postwar era." — The Daily News

Jens Müller was one of only three men who successfully escaped from Stalag Luft III (now in Poland) in March, 1944—the break that later became the basis for the famous film The Great Escape. Together with Per Bergsland, another Norwegian POW, he stowed away on a ship to Gothenburg, Sweden. The escapees sought out the British consulate and were flown from Stockholm to Scotland. From there they were sent by train to London and shortly afterwards to "Little Norway" in Canada.

Müller's book about his wartime experiences was first published in Norwegian in 1946 titled Tre kom Tilbake (Three Came Back). This new edition is the first English translation and will correct the impression—set by the film—that the men who escaped successfully were American and Australian. In a vivid informative memoir, Müller details what life in the camp was like and how the escapes were planned and executed, and tells the story of his personal breakout and success reaching RAF Leuchars in Scotland.

" The Great Escape from Stalag Luft III offers a fascinating look at the 1940s, recapturing the feel of both the war and postwar era." — The Daily News

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Great Escape from Stalag Luft III by Jens Müller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

In Camp

We went through a lovely landscape, broad valleys, fir-covered hills and green fields, where whitewashed farmhouses stood. We walked on a path across some fields and through a small forest. The camp soon became visible among the trees. It lay at the foot of a hill and from the path looked like a large farmhouse. I mentioned this to the Feldwebel, who explained that the houses we saw were a model farm just near the camp. We could not see the huts yet. The farm was run by young girls from town and other outskirts.

The Feldwebel pointed to a large house. ‘Headquarters,’ he said in good English, and I asked where he had learned it. Well, he had spent a couple of years in England just before the war.

‘How did you like Canada?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know,’ I said, ‘I have never been there.’

‘Is that so? I thought all Norwegians were trained in Canada.’ He showed me an American magazine he had, with pictures from Toronto. I said nothing, only thought it best to be on my guard.

We came to a courtyard overgrown with grass between low, long huts. Most of them had iron bars on the windows. The German led the way into one of the huts and after a great deal of talk with the guard I was taken in by them both. A long corridor leading into cells on either side ran right through the huts. The doors looked strong enough. We stopped at one of them. The guard opened the door and I was shown in.

‘And now give me your clothes, please.’

‘What?’ I said.

‘Kindly give us your clothes, we are going to search you.’

When I protested, explaining that I had already been searched, they said they regretted having to bother me again to take my clothes off. Well, there was nothing else to do but take off my uniform, keeping on underwear and socks. I had a small packet containing French money hidden in my socks. This money had been in the tin box with my emergency rations. They were not satisfied merely to get my clothes but examined my body all over on the outside and almost inside too! And found the money of course. ‘Aha,’ they said, and went away.

I looked around the cell. It seemed to be three by two metres. The furniture consisted of a bed, a stool and a table. On the bed was a mattress filled with wood shavings. In the table drawer I found a spoon, a fork and a wooden knife. The window could only be opened with a special key. A small opening over the window was nailed down but I got it open. Through the iron bars the view from the window was beautiful. The bars were very strong. I wondered if I would spend the rest of my days in this cell.

Then I remembered what they had told us in England about Durchgangslager Luft, Frankfurt am Main. Three or four Englishmen had managed to escape from Germany after having been in the camp.* Afterwards they had visited most of the RAF stations in England recounting their experiences. They had said something about a prisoner being kept in a cell all alone until the Intelligence Department was through with him. Only then was he let loose among the other prisoners.

I tried to remember all I had been told, about the microphone in the ceiling, about pleasant Germans and angry ones, about so-called Red Cross representatives and about Germans dressed as Englishmen. Germans could think of many things. Well, I was prepared for most of them. I wondered what time it was as my watch had been taken from me. A key turned in the keyhole and a Feldwebel entered. He had my clothes on his arm. He seemed a nice fellow, fair hair, blue eyes – cold eyes. I didn’t like them. His uniform was well pressed. He smiled broadly, ‘Good morning.’

I was surprised. He had quite an English voice and intonation, nothing German about his accent. He went on introducing himself and apologized for having kept my clothes and belongings for so long. I must have seemed uninterested because while he was talking I was trying to detect something German in his accent. But I couldn’t find anything. He sat down on the stool and kindly offered me a cigarette. I thanked him and took one. When I asked where he had learned English he willingly told me he had lived in England for many years. He had also been to America. He asked where I came from. ‘Oslo, Norway,’ I told him.

We chatted a while about different things and the German tried perceptibly to be entertaining and charming. He then pulled out a form. As he came around to the table to place the form before me I noticed a white band on his arm with a red cross on it. ‘Aha,’ I thought. ‘Here is the Red Cross form we were warned against in England.’ I read what was on it with curiosity. As expected, it started with the usual innocent questions. Gradually they changed from only personal (name, age, birthplace, etc.) to technical and tactical questions (station, squadron, leader’s name, number of planes, etc.) I filled out what I thought fit and said I was sorry I could not answer the rest of them.

The German first explained how necessary it was to answer all the questions. Necessary for informing authorities and relatives that I was taken prisoner. When I still refused his face grew dark. He said that if I didn’t fill out the form fully they had no other way of knowing if I really belonged to the RAF. I could be a spy for all they knew. Did I know what that meant? Yes, I knew. I still refused to complete the form.

At this point the German lost patience. He snatched up the form and left the cell. He must have gone through the same farce a hundred times, always with the same result. But he had played his part well, so well that he would perhaps bluff some if they had not been briefed and warned.

It was a relief to hear the door slam behind the German. I pulled at a rope hanging beside the door and expected a bell to ring which would bring the guard. Not a sound came from it. I knocked on the door and waited for the guard to come. No one came. Then I banged on the door. That helped. Heavy footsteps clanked along the corridor, the door opened and a soldier looked at me in astonishment.

‘Could I have a book to read?’ I asked. ‘And I want to wash myself.’

‘Yes, yes, just wait,’ was the reply. The German closed the door and his footsteps died away down the corridor. I lay on the bed and waited. One hour passed before footsteps were heard. The door opened and two soldiers entered with soup and plates in a basket. They placed a plate of soup and two slices of bread on the table and disappeared, wishing me ‘Good appetite’. Yes, my appetite was OK, but the thin soup and the two pieces of bread didn’t help much. I lay down on the bed and slept.

I heard the bolts being drawn back on the door and sat up. A German major entered the room.

‘Please, don’t get up,’ were his first words. I preferred to get up. He sat down and asked me to do the same. He offered me a cigarette. I waited anxiously for what was coming. We had been told so much about this camp and German methods of obtaining information that I expected to have military secrets pumped out of me without even knowing it. All the Germans I had hitherto come in contact with had used simple, direct methods for interrogation, methods which were easy to counter.

I expected this major to give me trouble – but his methods were as stereotyped as the others. I made use of his efforts to be friendly to ask him for some reading matter and toilet articles. There was of course nothing he would rather do than procure these for me. He expected me to thaw a bit and become more communicative. I must have disappointed him for he soon left me.

This was the last time I was cross-examined.

The most exciting event during the rest of the day was a walk along the corridor outside to the washroom. I then saw a Canadian being taken into his cell. We looked at one another but did not get a chance to speak. For supper we got two pieces of bread. The rest of the day I read or slept, and at night I slept like a log right up to 6.30 a.m., when breakfast was served.

The meal was soon eaten – the two pieces of bread only made me want more. One of the tablets I had eaten in the boat probably contained more nourishment that the two pieces of bread. After breakfast I sat on the bed and read, waiting for further Germans to come into my cell to search for information.

It was eleven o’clock when the sub-lieutenant came in with the good news that I was to be taken to the English camp. I got up and with four Canadians was taken out of the hut and two hundred metres down a short road which ended at the gate of the prison camp. Not one word passed between us. The others evidently felt and thought the same as I did. It didn’t bother me much being a prisoner. At that time I was very optimistic and thought I could manage to get home again in two months’ time. What I thought would be so nice was to meet RAF officers once more, to talk to people who weren’t German, to talk to friends.

I noticed that the Canadians’ footsteps also went faster as we neared the place. Inside the gate a small group of prisoners waited eagerly for our arrival. ‘Were there any old friends among the newcomers?’ And our thoughts were, ‘Is there anyone we know inside the fence?’

Only one of the Canadians and I saw no one we knew. The German who had brought us there and seen us safely through the gate disappeared and we were left to our allies. I did not know what to do so I kept a bit in the background and looked at the others. Soon we were surrounded by our fellow prisoners who deluged us with questions about everything under the sun – from baseball results to how we had got out alive. After a time, when their curiosity had been satisfied, the group gradually dispersed. They sauntered back to their huts in small groups.

A small red-haired squadron leader came up to me and introduced himself as the oldest prisoner in the camp. He was very friendly and told me among other things what would happen to us in the near future. This camp was only a temporary one. The place could hold eighty men, not counting the permanent staff. As soon as this number was reached, the required German guard was detailed, food distributed and prisoners sent by train to the so-called Stammlager. Durchgangslager Frankfurt needed about fourteen days to be quite full. Later, during the autumn of 1942, when the RAF started air raids on a large scale, it was necessary to enlarge the camp. Now only one-third of the places were occupied, and I could reckon on being in the camp for a week or ten days.

The squadron leader showed me around the place. We went first into one of the huts, to the room I was to sleep in. From there to the bathroom, the mess, the library (a cupboard in one corner of the mess), and at length to the canteen, where we could buy small things like ashtrays, picture frames, shaving articles, etc. I wondered where the money would come from and was told that the prisoners received part of their wages in German marks – not in ordinary marks which could be used in Germany but in special paper notes only valid in the camp. We could expect to get some of this money in a couple of days. As we walked along, the squadron leader had not asked any questions concerning military affairs, and I was glad because I was thus spared the unpleasantness of not answering them.

When we arrived back at the hut where I was to live he left me. Lunch hour in the camp was half past twelve and I had about half an hour left. I went into the living room. Five or six men in RAF uniforms were sitting there. I sat down on a stool and took a magazine. It would be good to have a look at one’s fellow prisoners before chumming up with them. In England we had been told so much about this camp, hidden microphones, Germans in English uniforms and other gadgets that I thought it best to be cautious. My fellow prisoners were evidently of the same opinion because they talked together in a very reserved and cautious manner. They seemed on their guard.

Then lunch hour arrived and all prisoners – we were ten officers and about twenty sergeants – trooped into our respective messes. I had expected a very spartan meal, consisting mainly of tea substitute, and was greatly surprised to see the table laid with toast, butter, jam and cakes. The tea itself was excellent. In time I learned how this comparatively good standard of food was kept up. This was one of the first camps to be formed for RAF personnel and had therefore a good regular connection with the International Red Cross. Food was packed and sent from England to Switzerland and from there the Red Cross sent it on to prisoner of war camps. The ration was one five-kilogram parcel per man per week, but on account of the through traffic this camp received more parcels than there were men and could thus accumulate a reserve fund of food. When there were new arrivals there was usually a sort of feast and this very much helped to raise their spirits.

After the meal I sat talking to the camp leader and adjutant in the dining room. The others left after a while and we were finally quite alone. Then the door opened and a tall man entered the room. I had seen him before somewhere.

‘Didn’t you once fly a Mosquito from Shetland in 1942?’* I blurted out. He looked at me coldly and with a dismissive remark ridiculed my question. Suddenly I remembered where I was and understood his behaviour.

Soon afterwards I went out to have a look at the camp and take in my surroundings. The piece of ground on which the camp was built could very well measure seventy by fifty metres, and three huts plus the mess made up the buildings. A small road went round the hut on the inside of the fence. As a rule our daily exercise consisted of walking round and round this road. I started – it took four minutes to make one round. I looked at the fence while I walked. It was about two and a half metres high; barbed wire was stretched between solid wooden posts. Two fences, one inside the other, with a one-metre space in between. In the area between them, barbed-wire ‘loops’ lay loose on the ground. The barbed-wire fences were not difficult to climb over, the danger lay in being caught in the loops. But the fence was not the only hindrance if one wished to get home again. I walked on along the edge of the road. A low wooden fence was put up about five metres inside the nearest fence. One of the first things the camp chief told me was that if I valued my life I would not go beyond this fence. German guards had orders to shoot without warning if a prisoner got outside the ‘warning wire’. And there were enough guards about. One of them patrolled the road outside the gate and in the four corners of the camp guards were posted in towers with their eyes on the camp.

For the time being I saw no possibility of getting out and in annoyance I had turned my steps towards the library to get a book when the tall man from the dining room came towards me.

This time he smiled broadly and shook hands with me. The picture from Sumburgh again came to my mind. It was a cold sunny day at the end of March 1942. The Norwegian fighter squadron was stationed on the Orkney Islands and had received orders to send a flight up to Sumburgh on the south point of the Shetlands because they had had several visits by German reconnaissance planes up there. Well, this sunny morning I and some others were on watch, and I can clearly remember the smart Mosquito which landed there. It was the first time I had seen a Mosquito and I tried to get into conversation with its pilot. He was not talkative – only said he was on his way to Norway where he would take photographs. He had just landed at Sumburgh to get his radio in order and fill up with fuel. While the mechanics worked we ordered food for him and his radio operator. They sat at a table in the dispersal room and ate in silence. As soon as the plane was ready they thanked us and were off.

We stood watching the plane climb eastwards and then disappear. That same evening the control officers told us that that very plane was missing – shot down by fighter planes. The airman, whom we all at that time thought was killed, was now beside me and recounted roughly what had happened. Everything had gone well on the trip over. They had taken a number of photos of Trondheim Fjord and the German naval base there.* On the way back they were attacked by Germans. The plane caught fire and they had to make an emergency landing in some field south of the fjord. German infantry was on the spot. The airman and wireless operator had only just time to help the fire in the plane a bit with the signal pistol when they were caught. They sat in prison in Trondheim for two days before being sent by rail to Akershus prison in Oslo. They were there for over a week before continuing on to Germany, to Dulag Luft, Frankfurt. He told us many small episodes from Akershus. About Norwegian girls working in the prison who helped prisoners. It was ages since I had spoken to anyone who had been in my hometown Oslo, and I asked how everything was there, but of course he could not tell me much because the journey from the railway station to Akershus had been by the police bus, called ‘Black Mary’.

He was now a member of the permanent camp staff. His wireless operator was safe in Stammlager Luft III. It was fun talking to him and the time passed quickly as we tramped six or seven kilometres round and round inside the fence. Then we parted.

The library was still open and I found a book which looked interesting. With this as a companion I found a spot in the sunshine and remained there until the other camp dwellers began to saunter towards the mess hut. It was time for the evening meal.

The tea table that afternoon had rather impressed me, but the one they laid out now was beyond anything I could have expected as a prisoner. If this continued I would not mind being a prisoner of war. As a little welcoming treat for us newcomers a film was shown in the sergeants’ mess after supper.

The show ended about one hour before the doors to the huts were closed by the Germans and everyone had to be in his respective hut. I had as yet not met my room mates. They were sitting there when I came in. Both were Canadians and their names were Bill and Hank. We sat on our beds and chatted a bit before turning in. The conversation was mostly about small topics but also touched on subjects about which we felt it best to be careful. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Maps

- Foreword by Jon Müller

- Introduction by Asgeir Ueland

- Shot Down!

- The Rubber Dinghy

- Prisoner

- In Camp

- The Last Days

- Stettin

- Epilogue

- Plate