eBook - ePub

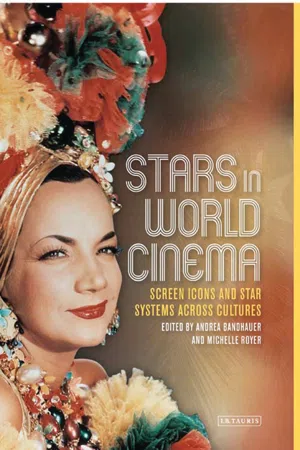

Stars in World Cinema

Screen Icons and Star Systems Across Cultures

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Stars in World Cinema

Screen Icons and Star Systems Across Cultures

About this book

Deflecting the attention from Hollywood, Stars in World Cinema fills an important gap in the study of film by bringing together Star Studies and World Cinema. A team of international scholars here bring their expertise and in-depth knowledge of world cultures and cinema to the study of stars and stardom from six continents, exploring their cultures, their local history and their global relevance. Chapters look at the role of acting, music, singing, painting and martial arts in the making of stars from Australia's indigenous population, Austria, China, Egypt, France, Germany, Greece, India, Iran, Japan, North and South Korea, Nigeria, the Philippines, the former Soviet Union, Spain, North and South America.

Since the very beginnings of cinema, actors and stars have been central to its history and have been one of the medium's defining characteristics. They have also been fundamental to the marketing of cinema and have played a major part in the reception of films in many cultures. Stars in World Cinema examines stardom and the circulation of stars across borders, analysing how local star systems or non-systems construct stardom around the world. Contributors put into practice their local knowledge of history, language and cultural systems, to consider issues of hybridity, boundary crossing, the mobility of stardom, and embodied spectatorship, in order to further the understanding of stars in light the of recent interest in reception theory.

Rooted in a multidisciplinary and polycentric approach, this book throws light on unexpected connections between stars and stardoms from different parts of the world, cutting across chronology, geographies and film history.

Since the very beginnings of cinema, actors and stars have been central to its history and have been one of the medium's defining characteristics. They have also been fundamental to the marketing of cinema and have played a major part in the reception of films in many cultures. Stars in World Cinema examines stardom and the circulation of stars across borders, analysing how local star systems or non-systems construct stardom around the world. Contributors put into practice their local knowledge of history, language and cultural systems, to consider issues of hybridity, boundary crossing, the mobility of stardom, and embodied spectatorship, in order to further the understanding of stars in light the of recent interest in reception theory.

Rooted in a multidisciplinary and polycentric approach, this book throws light on unexpected connections between stars and stardoms from different parts of the world, cutting across chronology, geographies and film history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stars in World Cinema by Andrea Bandhauer, Michelle Royer, Andrea Bandhauer,Michelle Royer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section 1

Film Icons and Star Systems

1

‘I Love You When You’re Angry’: Amitabh Bachchan, Emotion and the Star in the Hindi Film

There are many books about Amitabh, and thousands of websites document his life. He was born in Allahabad, at that time in the United Provinces of British India, first son of Hindi author Harivanshrai Bachchan and Teji Bachchan. After a few false starts in the film industry, Amitabh’s career followed several strands, including his superstar role as the ‘Angry Young Man’ and also as a comedian and romantic hero in the mainstream Hindi film industry, as well as his considerable success in the more realist ‘middle-class cinema’ of Hrishikesh Mukherjee. With over 160 films listed on IMDb, he ruled the box office in the 1970s and much of the early 1980s. The 1980s were a turbulent period in Bachchan’s life, marked by a sojourn in politics, a near-fatal accident on the set of Coolie (Manmohan Desai) in 1981, and years clearing his name in court of any association with the Bofors scandal. 1 He retired from films in the 1990s, and launched an ill-fated entertainment company, ABCL. After 2000 he found film roles more suited to an older hero, and won a new fan base for his version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?, Kaun banega crorepati? Voted Star of the Millennium by the BBC, he was the first Indian film star to have his waxwork likeness installed in Madame Tussauds.

Amitabh married his co-star Jaya Bhaduri in 1973, and their son, Abhishek, is a film star in his own right. In 2007 Abhishek married one of the top female stars, the former Miss World Aishwarya Rai, who was seamlessly incorporated into the Bachchan family brand.

Star Theory – Amitabh and Indian Cinema

Star theory, which was developed mostly in the context of Hollywood by Dyer (1979, 1986, 1998) and Ellis (1992), and later by Gledhill (1991), Stacey (1993) and others, is based on the idea of the star text. Dyer (1979: 34–7) argues that the star is the focus of dominant cultural and historical concerns, thus creating interest in the life of the star and their whole off-screen existence, to produce a star text, which is an amalgam of the real person, the characters played in films, and the persona created by the media, which has an economic and institutional base. Gledhill (1991: 214) sums this up by saying stars ‘signify as condensers of moral, social and ideological values’.

Amitabh’s career exemplifies the idea of the star text. His dominance is explained as his role as the ‘Angry Young Man’, where his private anger expresses the public anger of the time, mostly caused by the breakdown of political consensus (Prasad 1998: 117–18) and social upheaval. Much of what is known about Amitabh is conflated with his on-screen star roles. He has acted in many great roles, whose intertextuality is reinforced by the nature of the Hindi film itself.

Amitabh’s roles were unusual in that throughout the 1970s and early 1980s he often performed as two characters, Vijay and Amit. The latter is a more traditional romantic hero, but this chapter focuses on Amitabh’s role as Vijay, usually called ‘the Angry Young Man’, created by the writers Salim (Khan) and Javed (Akhtar). The character of Vijay appeared in films scripted by Salim-Javed for various directors, including Ramesh Sippy, Prakash Mehra and Yash Chopra (Kabir 1999: 68). Amitabh also plays a character called Vijay, who has many similarities, in Roti, kapada aur makaan, written and directed by Manoj Kumar (1974).

Vijay’s story may alter, but he is someone who confronted injustice in childhood, such as in having his parents killed (Zanjeer, Prakash Mehra, 1973), being illegitimate (Trishul, Yash Chopra, 1978), being abandoned (Deewaar, Yash Chopra, 1975), seemingly having no family (Jai in Sholay, Ramesh Sippy, 1975), or in seeing himself as wronged by his own father (Shakti, Prakash Mehra, 1982). His adult life shows Vijay fighting a personal war against the wrong done to him, where evil is usually embodied by a single figure or villain. Vijay breaks the law, but we can believe he is right, at least most of the time. We admire his self-respect, the respect afforded to him by others, and his moral rectitude in dealing with women, elders and youngsters. His religion is a more complex area. When Vijay feels God has abandoned him, he gives up on Him (Deewaar), but he usually manifests equal regard for all faiths, with demonstrable respect for the major faiths in India – Hinduism, Islam and Christianity. However, Vijay often has to perform some form of sacrifice or atonement, such as in Kala Patthar (Yash Chopra, 1979), where a single mistake leads to years of penance and to his risking his life working in a coal mine. Vijay is often fixated on his mother and let down by his father, leading to a seemingly Oedipal conflict where he avenges his mother by taking revenge on his father. This goes to the extreme in Trishul, where Vijay’s revenge destroys his father’s life and business, and it is only the father’s death that can bring about reconciliation for his treatment of Vijay and his mother.

Amitabh’s character development was restricted by his star persona.2 Vijay was always Vijay, whoever was directing, and Amitabh brought other performances of Vijay to all the films in which he acted. Vijay seemed to incorporate other star personas – romantic, comic – elements that didn’t belong to his character, perhaps drawn from his other main character, Amit, the romantic hero, while Vijay’s anger infects Amit’s roles. The naming of the hero was important, as it suggested some intertextual references between the films and the sense of a particular character as an alter ego of the star – Amit, for example, being a shorter version of Amitabh’s own name, while Vijay’s name itself (‘Victor’) exemplifies the kind of hero he was going to be in the film. Vijay had many character traits that linked him across films, notably his rebelliousness, which often goes against the state. Other features of Vijay have been clearly ascribed to Amitabh himself over the years, such as his anti-communal stance, often showing a closeness to minority communities and his roles as a devoted son, husband, lover, poet or lover of poetry, manifesting seriousness and gravitas.

Although Vijay’s name shows him to be a Hindu, and he is usually north Indian, though from different communities, Amitabh’s standing as an all-Indian hero has been reinforced by his playing characters from different regions and communities. These include roles as a Bihari Muslim (Saat Hindustani, K.A. Abbas, 1969), Christian (Amar, Akbar, Anthony, Manmohan Desai, 1977), Rajput (Laawaaris, Prakash Mehra, 1981), Bengali Brahmin (Anand, Hrishikesh Mukherjee, 1971), Khatri (Zanjeer, Prakash Mehra, 1973) and Kayasth (Khuddar, Ravi Tandon, 1982). Amitabh has not played characters from low-caste communities – OBCs (Other Backward Castes) or SCs (Scheduled Castes, Dalits) – but this it is not surprising given that they rarely feature in mainstream Hindi cinema.3 In all these films, Amitabh uses his great command of language and dialects to portray these roles, using sociolects and other quirks to give them symbolic charge. Yet, although he argues with Maharashtrian nationalists that Mumbai is now his karmabhoomi (place of work), and he is probably its highest individual taxpayer, he is closely identified with his janmabhoomi (place of birth), Allahabad in UP. His roles suggest that Amitabh can be seen as the all-India star who can easily identify with and slip into other roles.

One feature of the star text is knowledge of the star’s off-screen biography, however manufactured this may be for publicity or for effecting intimacy. We know little about Amitabh’s day-to-day life and what he is really like.4 Nor does he offer any revelations to the media, which has long been obsessed with his relationship with his co-star Rekha. Amitabh is, however, active on social media, where he blogs and has Facebook and Twitter accounts.

Star theory was developed in the context of Hollywood, which has striking differences from Hindi cinema, not least in the latter’s loose and non-corporate structures, which impact on the media creation of the star. Indian stars are not promoted by PR companies and studios and rarely have agents, only managers who deal mostly with finance and booking.

Mishra (2002: 127) argues that, while Indian cinematic stars are created in ways similar to those of the Hollywood star model, Hindi film deploys song and dialogue in specific ways to create stars. He rightly notes Amitabh’s key dialogues, which are some of the most quoted dialogues in Hindi film history, still known by millions of Indians. Amitabh sang some of his own songs from the late 1970s, though his voice in his dominant period was that of the playback singer, Kishore Kumar. Yet Amitabh does not sing (or mime to a playback singer) in the film that launched his career as a star, Zanjeer, or in Deewaar, while in Sholay his only song is at the beginning of the film (‘Yeh dosti/This friendship’).

Star theory explains much about Amitabh and his role as Vijay in the 1970s and 1980s, and accounts too for his global popularity. However, the moniker ‘Angry Young Man’ asks us to look more closely at anger in film, especially Indian cinema, in the context of the emotions and the emotional foregrounding of melodrama, and why Vijay/Amitabh was so successful in conveying such anger.

Emotion

The melodramatic mode of Hindi cinema foregrounds emotions, and the audience responds to them in the cinema with strong reactions that, apart from laughter, would be mostly hidden or subdued in a Western cinema hall. Emotions underlie the complex relationship of the audience to the star and the role of the character in keeping the audience’s interest in the film – in particular, why Indian film audiences have been so interested in Vijay’s anger and its manifestations.

Emotions shape our social and cultural lives. Popular discussion of emotions draws on Aristotle’s concept of catharsis and Freud’s understanding of the human mind. Scholarship on the topic is interdisciplinary, as discussed in Oatley and Jenkins (1996), while there are key texts by philosophers, who often pay special attention to the arts and work centred on the arts (Altieri 2003; Feagin 1983; Grodal 1997; Keen 2007; Levinson 1982; Robinson 2005; Solomon 2004; Wollheim 1999). Much published research in this field has concentrated on the West, even though it has been noted that, while some emotions are universal, others are culturally specific (Averill 1980; Ekman 1994; Lutz 1998). Little has been written about the study of the emotions in India other than in Lynch (1990). Even the famous ancient theory of rasa (emotion) has been discussed in the context of Sanskrit aesthetics rather than that of wider studies of the emotions.

Film studies have barely engaged with emotions except in the discussion of melodrama (Elsaesser 1972; Gledhill 1987; Mulvey 1977/8; Neale 1986), which has been researched in Indian film (Dwyer 2000; Dwyer and Patel 2002; Prasad 1998; Thomas 1995; Vasudevan 1989, 1998), and the changing role of the sacred (Brooks 1995; Dwyer 2006a).

Melodrama seeks to elicit an excess of emotional response from the audience. The West, or at least northwestern Europe, following Kant, has long disparaged the emotions and their expression in favour of reason, although this situation is changing with the recent rise of a new public emotionalism – a demand to feel rather than to think (Anderson and Mullen 1998). The academic study of the emotions has shown that the division between reason and emotion is far from the binary it is taken to be on a popular level, with emotional responses being an important part of the reasoning process. The division of reason and emotion was established in India only at some levels as part of a wider colonising of the mind, by European Enlightenment thought, and an emotional response to texts, including films, is seen as normal in India (Chakrabarty 2000).

It is not entirely clear how a film elicits emotions from the audience, though it can do so by portraying characters, showing emotions and creating a mood through visuals, music, narrative and so on. The Hindi melodrama stirs up several emotions rather than a single one, yet the way in which a film isolates particular emotions has not been examined in the Indian context.

The role of the emotions has implications in film-viewing practices, which in India are generally acknowledged to be different from those of Western cinema audiences (Srinivas 1996). Identification, the popular view of audience involvement with fictional characters, is seen by Neil (1996) as one way of responding to fictional characters. Murray Smith’s (1995) stimulating theory suggests that the spectator’s relationship to film is one of an emotional relationship to the characters, in contrast to the commonly held view that it is based on identification; while Grodal (1997) explores how emotion structures attention to narratives and generic structures in films.

Caroll (1997), arguing strongly against identification, suggests that the complicated relationship we the audience have with characters on-screen perhaps reflects a neo-Platonic view, a relationship between onlooker and observer. Characters behave; audiences entertain thoughts and emotions. We do not identify with characters; we do not become them. This means we are happy that Amitabh or his character is in love but we are not in love with the object of his love. We can be angry with him when no one else in the film is, or we can love him when no one else does. For example, when Vijay is sad, we may not feel sad but we may admire him for his self-sacrifices and his fortitude while he is not admiring himself. We can also see the world empathising with him so we too can feel angry when he does, even though we may not entirely agree with him; in Trishul we may understand his anger without approving of it. We can also see Vijay through the eyes of other characters in the film – he usually has a mother and a best friend of a brother – and like them, we can admire him and support him, even when we know he is doing wrong.

These theories of emotion need to be re-examined in an Indian context, linking them to audience research and fan culture, which again have been developed in a largely Hollywood or British context (Dyer 1986; Kuhn 2002; Mayne 1993; Stacey 1993; Staiger 2000).

A simplistic argument about the popularity of Amitabh’s anger has often been suggested – namely, that the 1970s was a particularly violent and troubled decade in India’s history, whose nadir was the State of Emergency (1975–77), and that Amitabh expressed the zeitgeist. This was much refined by Prasad (1998), who argues that the political upheavals and the breakdown of consensus between dominant power groups were particularly radical during this period. However, other decades were as, if not more, troubled. It is also striking that other world cinemas also became more violent in the late 1960s and early 1970s, with the global popularity of Clint Eastwood’s westerns and Bruce Lee’s kung fu films.5

But Amitabh’s films are not necessarily violent and bloody. There is less emphasis on the spectacle of violence (Deewaar has one famous fight sequence in the warehouse) than on anger and vengeance. Many film heroes before Amitabh were also angry, but their anger was somewhat different, and Amitabh’s anger had a particular resonance with audiences.

In Hindi films, anger is often destructive, and usually self-destructive. The archetypal hero, Devdas (Dwyer 2004), as his anger with his family, society and the women in his life leads him into ineffectual and impotent rage where he abandons his family, refuses the proposal of his childhood sweetheart whom he loves, and later scars her face in anger, rejects another woman who loves him, ditches his friends, and ultimately destroys himself through low living. This angry hero is an ancestor of Vijay, who also broods and is maudlin and usually has unsatisfactory relationships with women other than his mother, but Vijay’s anger is also located in the wider world, connecting him to other heroes, such as Birju (Mother India, Mehboob Khan, 1957) and Ganga (Gunga Jumna, Nitin Bose, 1961), whose anger was in a good cause and often effectual, but which eventually had to give way to the law, which often demanded the hero’s life. The hero who is beautiful and has to die young, tormented by an unjust world, is a popular figure in many narratives.6 Amitabh’s anger is that of the romantics and of the fighter for his family values, but is mixed with the style of the streetwise, portrayed by Dev Anand, one of the greatest heroes of Indian cinema in the 1950s and 1960s, as well as being reminiscent of that of other Hollywood heroes.

Anger as an Emotion

Anger has cultural, moral and political meanings. It is often viewed as dangerous and uncontrollable, but not always as a negative emotion.7 Plato argued that reasoned anger is necessary for us to pursue justi...

Table of contents

- About the Author

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Star Studies and World Cinema

- Section 1: Film Icons and Star Systems

- Section 2: Stardom Mobility and the Exotic

- Section 3: The Politics of Stardom

- Section 4: Stars, Bodies and Performance

- Bibliography