![]()

CHAPTER 1

EURASIAN ‘OTHERING’

Several authors have sought to establish how, when, and why the Eurasian community came into being.1 All agree that the beginnings of a Eurasian community of British and Indian descent followed a series of ‘proscriptions’ formulated between the 1770s and the early nineteenth century.

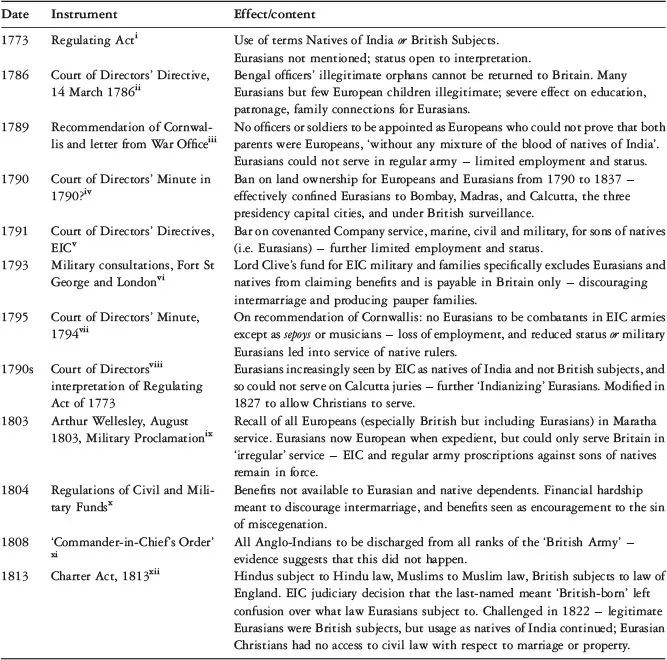

The effects of legal proscriptions (Table 1.1) and informal ‘usages’2 were to deny Eurasians a fully British identity and the educational opportunities open to their European relatives, to restrict opportunities for employment and financial reward, to promote downward social mobility, and to lower their status. Authors vary on the ‘proscriptions’ they consider most important and what motives and effects they had, but all identify some of these directives as the ‘push’ that set Eurasians apart, causing them to come together into a nascent community.

This chapter reassesses the link between ‘othering’ and discrimination against Eurasians, and will comment on the interpretations provided in earlier accounts. I show how each change affected the community, but also that this approach cannot fully reveal the motivation behind the proscriptions.

1773: CONFUSION OVER NATIONAL STATUS3

The 1773 Regulating Act was identified by Hawes and Goodrich as the first Act to differentiate between Natives of India and British Subjects.4 The terms imply belonging to one ‘nation’ or other, neither of which had evolved a truly national identity. Nineteenth-century nationalities were nuanced by subcategories: e.g. martial Sikhs and Highlanders, ‘primitive’ Irish, and ‘tribals’. ‘British subject’, a term that technically defined all within the British empire, was in reality shorthand for European ‘whites’ born in Britain or wherever their parents were temporarily domiciled. ‘Native of India’ meant non-European. Confusion resulted over what the terms meant for Eurasians, because their status was not addressed. For education, employment, defence, marriage, and access to law, Eurasians could be categorized simultaneously as European British Subjects, non-European British Subjects and Natives of India. In native states, they were never certain whether they would be subject to Muslim or British law. British administrators did not know whether to include Eurasians in returns on British subjects or not. There was no official designation for anyone of mixed race until 1827, when the inclusion of Eurasian widows (and continued exclusion of native widows) in Lord Clive's Fund prompted the British to define them.5

Uncertainty over Eurasians' nationality persists today, when many Anglo-Indians have adopted new countries, and others, despite Indian constitutional recognition as an Indian minority group, remain uncertain that they are accepted as ‘native’ by other citizens of post-colonial India. Eurasian national identity united Eurasians, in the sense that it posed a problem, but divided them along lines of language, ethnicity, gender, class, legitimacy, and other factors that define ethnicity or delineate community.

It is unlikely that the 1773 Act deliberately set out to strip Eurasians of British nationality since many Eurasians were still recognized by their extended British families, were still in government service, were still educated in Britain, and were in every sense British. The indecision of the next 50 years could have been deliberate, since it would have been easy to include a clause identifying them as either British subjects or natives of India. That lack of clarity was useful to the administration, which could include or exclude Eurasians as circumstances dictated. Later changes to the laws and regulations governing Europeans in India led to the increasingly frequent exclusion of Eurasians from the status of British subjects. The 1773 Act could, therefore, have been the first stimulus to Eurasian group formation.

Table 1.1 Summary of Proscriptions Seen as Inimical to Eurasian Interests, 1773–1813.6

1786: EURASIAN ORPHANS TO REMAIN IN INDIA7

In March 1786, the Company's directors resolved that the Bengal Military Orphan Society must not send officers’ orphaned children to Britain for education unless they were legitimate8 and of wholly European parentage. There had been arguments under this head in Bengal since the inception of the society. In November 1782, the managers asked Commander-in-Chief Eyre Coote to present their case to the governor and Council. They addressed objections already raised by persons unnamed ‘whose opinions we have always respected very highly.’ Amongst the objections cited, one was explicitly racial:

the imperfections of the children, whether bodily or mental; that is whether consisting in their colour, their conformation, or their genius, would, in process of time, be communicated, by intermarriage, to the generality of the people of Great Britain; and by this means debase the succeeding generations of Englishmen.9

The managers counter-argued:

it might, we conceive, be safely presumed, from the silence of the Legislature on this head, that the evil apprehended by some persons here must be altogether imaginary … children of the same complection [sic] in the West Indies and America who have been educated in England, have neither proved chargeable to society, nor disgraceful to the human species.10

Several authors identify the 1786 Directive, and the discussions that preceded it, as significant because it heralded a divergence in prospects for European and Eurasian children.11 Its effect was that Eurasians were excluded from following their fathers into Company service as ‘gentlemen’. There was no law preventing a father purchasing a passage to Europe for his Eurasian children, and many continued to do so; racial categories remained flexible where there was wealth and influence. Once a boy was in England, however, his return to India could be blocked if it were contingent on Company employment. Thus, well-educated and wealthy Eurasians often stayed in Britain. A minority succeeded in gaining Company appointments and returned to India.

Employment prospects for those remaining in India as children were effectively blocked by their lack of a British public school education and influential patrons. Most Eurasians were, of course, unaffected directly by this order since, as the children of ‘lesser men’, most would have stayed in India anyway, and had only rudimentary education whether they were in England or India: their prospects were limited by class rather than access to patronage.

1789: ALL EUROPEAN CROWN ARMY12

When appointed governor-general in 1786, Cornwallis insisted on freedom to act as he saw fit and to overrule the Supreme Council when he wanted to. Burke objected when the bill was at committee stage: ‘the principle of the bill was to introduce an arbitrary and despotic government in India’. He thought it unlikely that the decisions of one man could be fairer than the decisions of three (the Supreme Council). Nonetheless, the Bill was amended and the governor-general granted arbitrary powers.13 Commanding all Crown regiments posted to India, Cornwallis banned ‘officers and men born of black women’ because of ‘the injuries which would accrue to the discipline and reputation of HM's troops employed in India’, and received retrospective War Office agreement.14 Although Cornwallis was able to deploy Company troops as he wished without prior reference to London, it was two years (1791) before the directors banned recruitment of Eurasian officers for its armies.

The motives behind the exclusion of Eurasians from covenanted and commissioned posts were complex.15 Valentia and, later, Stark cite fear that Eurasians would ape the ‘mulattos’ of San Domingo who led an uprising, a theory dismissed by Hawes since Haiti's revolution came later.16 Fear of what could happen when colonists and settlers sought sovereignty was, however, a contemporary issue for many Britons and for Cornwallis in particular. He had, after all, been the commander of defeated British forces in America in 1781. He had first-hand, bitter experience of a settler army, aided by France and utilizing guerrilla warfare techniques adapted from Native Americans.

1790: RESIDENCE AND LAND OWNERSHIP RESTRICTED17

A ban on land ownership and rights of residence (cited by Anthony, Stark, and Hawes)18 obliged Europeans and Eurasians to live within ten miles of a British settlement. Ross states: ‘at this time no Europeans, except military officers and covenanted servants, were allowed to reside out of Calcutta, without a special license’.19 The reforms determined:

no British subject (excepting King's officers and the civil and the military covenanted servants of the Company) shall be allowed to reside beyond the limits of Calcutta, without entering into a bond to make himself amenable to the court of justice of the district in which he may be desirous of taking up his abode, in all civil causes that may be instituted against him by natives.20

Eurasians were included in this proscription; James Skinner's reward of a jaghir (for military services) was withdrawn because of it, and it was two years before government allowed him to exchange his pension for land near Delhi.21 The ban was restated in the Charter Act of 1813, though the boundaries had been extended:

nothing herein contained shall extend, or be construed to extend, to authorize the holding or occupying of any land or other immovable property, beyond the limits of the said several presidencies, by any British subject of his Majesty, otherwise than under and according to the permission of the Governments of the said presidencies.22

Eurasians sometimes used confusion about their nationality to advantage by asserting that they were not Europeans and were therefore exempt from this ban. Company policy, however, was to ‘discourage’ this ‘troublesome’ class.23 George Sinclair was ‘discouraged’ in his ambition to become an indigo planter in a native state in 1832, because a Eurasian would likely be ‘productive of future embarrassment’.24 Since Sinclair later set up his indigo concern within Company territory, and ran it successfully for many years, the embarrassment did not reside in his business acumen.

The ban was relaxed in 183325 for those with government permission, and removed in April 1837:

It is hereby enacted, that after the 1st day of May next, it shall be lawful for any subject of his Majesty to acquire and hold in perpetuity, or for any term of years, property in land, or in any emoluments issuing out of land, in any part of the territories of the East-India Company.26

That still did not allow Europeans or Eurasians licence to reside or work in native states, which were bound (or treated as though bound) by treaties requiring them to seek the express permission of the British before entertaining any ‘foreigner’:

it is an important principle of Imperial policy that the entertainment by Native States of foreigners, whether European British subjects or other Europeans or East Indians, should be controlled … this principle is affirmed and maintained by the Government of India irrespective of our treaties.27

Government still considered Eurasians in Native states to be a ‘troublesome’ class, and it was easier to eject Eurasians than upset relations with the British. In 1882, the Nizam of Hyderabad was asked by the Resident by what authority he had employed a Eurasian called Butler; rather than answer, the durbar dismissed him.28

Whether to prevent access by native durbars to European expertise, to prevent exploitation of Indians by Europeans, or to discourage attachment to India, the effect was to urbanize the European and Eurasian population. Inclusion of Eurasians in the land ownership ban hit them disproportionately hard. Europeans could always buy property ‘back home’, whereas Eurasians born and bred in India, who were rarely wealthy, were unlikely ever to do so. It limited opportunities to diversify into employment or subsistence other than in commerce or government service. Thus, later proscriptions limiting government employment were particularly damaging to Eurasians.

1791: EMBARGO ON APPOINTMENTS TO COVENANTED POSTS

In April 1791, The EIC directors decreed ‘no Person, the Son of a Native Indian, shall henceforward be appointed by this Court to employment in the Civil, Military or Marine Service of the Company’.29 This order follows from the 1789 War Office order with respect to the Crown Army.30 Hawes says that the order was not retrospective, although few Eurasians were henceforth appointed; those already in post continued to serve.31 The wording of this order said no appointments would be made by the Court of Directors. A second ord...