![]()

CHAPTER 1

INCORPORATION INTO CAPITALISM: FROM A COMMERCIAL HUB TO A BOOMTOWN

In the Ottoman Empire, the privileged geographical positions of port cities and port towns turned them into principal hubs of contact with the world capitalist economy as early as the late eighteenth century. The histories of those commercial centres, however, reveal that they had been active centres of trade and commerce before that time as well. Those hubs often existed ‘prior to capitalist expansion, within agrarian empires. These empires normally sought to establish a closed and compact division of labour within their boundaries, and, therefore, attempted to minimize economic “leaks”’.1 The port cities and port towns of agrarian empires often provided for domestic demands and in line with that their commercial activities were closely monitored and controlled by imperial centres. Looking at these ‘pre-capitalist’ histories of port cities and port towns thus helps clarify why the sovereignty of their respective centres were considered to be ‘contested’ with the coming of capitalist incorporation. Eski Foça was one such commercial hub of the predominantly agrarian Ottoman Empire and attempts were made to minimize ‘leaks’. A brief look at the history of Foçateyn and Eski Foça before the period of incorporation will reveal the dramatic nature of the change that later occurred.

When Foçateyn came under the control of the Ottomans in 1455, it had long been enjoying the business brought by the Genoa-Istanbul-Kefe2 trade route thanks to its alum mines. Foça was under Byzantine rule before 1275, after which the Genoese merchant and diplomat Manuelle Zaccaria managed to rule it de facto by turning Foça into a Genoese mining outpost. The Zaccaria family controlled the alum mines in the Foça area and they were operated by more than fifty workers per mine, a number that was very high for the period.3 Until the Ottoman conquest in 1455, Foça remained an area of contestation among the Byzantines, Genoese and the Turkic principality of Saruhanoğulları (the Sarukhanids).4 Throughout this time, both Eski Foça and Yeni Foça, the two largest settlements in Foça, maintained their positions of prestige. Eski Foça was an exporting port town and Yeni Foça was a mining colony. The coming of the Ottomans had an immediate impact on the export-oriented production of Foçateyn. By the time of Ottoman rule, an alternative source of alum near the Papal lands of Rome in Tolfa5 had already weakened the importance of Foça in medieval trade networks. However, alum production in Foça continued, and the region was still supplying international demand. A decisive change came about with the Ottoman decision to direct alum supply for the demands of the domestic market. The Ottomans fixed the price and prioritized the domestic market over international trade. This diminished the importance of the alum trade in Foça6 since the demand for exports was far greater and prices were not fixed. Nonetheless, the Ottoman conquest did not dramatically alter the economic role of agriculture, other forms of mining and fishing. Eski Foça remained as the centre of commerce.7 This was because of the Ottoman domestic market's need for the resources that Foçateyn produced and the maintenance of domestic trade through hubs like the port of Eski Foça. However, the very logic of Foçateyn's economic activities was reshaped within the framework of Ottoman provisionism (the iaşe system). In essence, Ottoman provisionism represented a command economy in which prices were fixed by the state. It required that all production first be directed to supply domestic demand, and that meant the end of export-oriented production for the salt, alum and stone mines of medieval Foça.

Daniel Goffman has pointed out that from the end of the fourteenth century onwards, after the conquest of the majority of Western Anatolia by Bayezid I (with the exception of Izmir), the volume of trade in the Aegean (the Western Anatolian shores) was almost equally divided among towns like Foça, Selçuk, Balat, Urla, Çeşme and Seferihisar, all of which had populations of around a few thousand people. This picture changed at the beginning of the sixteenth century after the conquests of Mehmet II (the Conqueror) which brought the entirety of Western Anatolia under Ottoman control. After the Ottoman conquest, most of the ports in Western Anatolia that had been important since the fourteenth century lost out to Izmir and only a few important hubs remained active.8 Afterwards, Izmir started to grow as the commercial hub of the Ottoman domestic economy. In the mid-sixteenth century, commercial contact with Italy, which had been maintained through the Genoese rulers of Chios who sent ships to Çeşme, vanished. Ships no longer circulated goods and as a result customs dues declined.9 This downward trend in commerce changed towards the end of the sixteenth century as towns like Foça, Seferihisar, Balat, Izmir, Edremit and Ayezmend (Altınova) became important ports in the Ottoman era,10 re-emerging as the commercial hubs of a growing agrarian empire. Although the coming of the Ottomans initially took its toll on the volume of trade, an enlarging empire with a burgeoning capital city and a growing domestic market re-established the need for Western Anatolian ports.

Around the 1650s, Eski Foça was one of three places (along with Izmir and Edremit) that had extensive relations with the Istanbul trade network thanks to its alum mines, millstone production and dried fruit.11 The reason for this ‘extensive’ connection was Istanbul's needs, and Eski Foça was one of the three major ports on the Western Anatolian coast that served the capital. Eski Foça port shipped Foçateyn's goods almost exclusively to the capital. Imperial orders stipulated that the needs of Istanbul were a priority and that goods first had to fulfil the capital's demands, which often meant the whole of production. Foçateyn's major products were crucial for the provisionist Ottoman economy.

Alum was used in making medicine, as well as in the paper and dye-making industries. However, around the sixteenth century alum production gave way to salt mines12 and subsequently salt production became the major mining activity in the county. The percentage of salt in trade grew exponentially after the sixteenth century and peaked in the early twentieth century. There were multiple salt mines and methods of production, and Yeni Foça was no longer the centre for extraction as had been the case with alum. Eski Foça turned out to be better for extraction and transport thanks to its proximity to salt mines such as Çamaltı, and this brought about the loss of prestige that Yeni Foça enjoyed in the medieval period. Under Ottoman rule, Eski Foça gradually became the more dominant of the two towns.

As a pillar of the provisionist (iaşe) network, Foçateyn was the supplier of millstones (seng-i asiyab) for Istanbul and their purchase from elsewhere was illegal since their production was the only output of the millstone taxable unit (seng-i asiyab mukata'ası) in Foçateyn. Millstone production added further prestige to the port of Eski Foça after the eighteenth century when there was an increase in demand.13 Since mills were essential for the processing of grain, millstones were also essential goods for the domestic market. This was even more important in the Ottoman provisionist logic since the constant supply of grain to the masses was vital in avoiding famine and the disorders that ensued when it became widespread. With provisionism, sustainable bread production was linked to the security of the capital, and hence bread production in Istanbul was directly linked to both the extraction and the shipment of millstones from Foçateyn. Dried fruits were the main source of sugar at a time when sugar cane was an expensive commodity, and Foçateyn produced various fruits and supplied them to Ottoman and foreign markets. Its most important good was grapes and the county was particularly famous for its purple variety. All these goods from Foçateyn were directed to the domestic market unless imperial permission was granted for them to be exported.

The adaptation of the market to Ottoman provisionism meant that the powers in Istanbul determined what was to be shipped where and for how much. In the late sixteenth century, Eski Foça also became an important transit port in the supply route of the capital's wheat, and rice, dried fruits, leather (sahtiyan) and beeswax were among the goods that were supplied to the capital through Eski Foça.14 Despite the gradual adaptation to the system and the rigorous Ottoman supervision of trade, Western Anatolian producers and traders sought ways to avoid the central pricing system of Ottoman provisionism. Stocking and hiding goods to drive up market prices, as well as smuggling, piracy and fraud, were among the tactics they used. Among these methods, which were often employed simultaneously, piracy and the smuggling of goods became the dominant means of sustaining export activities.

There were two types of pirating in the Aegean and they were carried out until the demise of the Empire to varying degrees. There were pirates who worked through domestic networks and others connected to foreign networks. Domestic piracy drew its labour mostly from smugglers in regions where pirates were active. They often made small raids and attacked rival towns. Faroqhi has pointed out that despite the fact that those pirates engaged in skirmishes with rival towns that had communities with different religious or communal identities, this was often more of an excuse than a reason. Pirates in domestic networks relied on the logistic support of their region for water, food and shelter. Their collaborators were often the people who were supposed to track them down, and domestic pirates’ interdependence on local networks made them somewhat less dangerous. In contrast, pirates from other regions represented the greatest danger, and they enslaved people and pillaged towns and villages on a larger scale because they were alien to domestic networks. Such pirates even dared smuggle goods that were most rigorously monitored by the Ottoman government, and they played a major role in the smuggling of grain to European ports.15

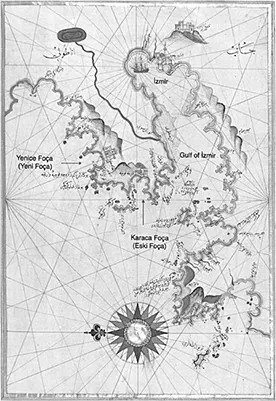

Foçateyn attracted pirates as a result of its position as the commercial hub of the agrarian empire. Eski Foça was one such Ottoman port town in the Aegean where both the grasp of Ottoman provisionism and the ‘leaks’ created by piracy and smuggling existed. The global market tried to obtain goods from the Ottoman economy but was only able to do so on a limited scale through capitulary agreements. Therefore, both smuggling and piracy were instrumentalized as a means to extract more from the Ottoman economy. For instance, from 1565 to 1568 French and Venetian ships secretly entered Eski Foça port to smuggle various goods, including dried fruits and grains.16 Thanks to its privileged position on the coast and the protective nature of its harbour, Foçateyn became attractive not only to European investors and traders but also to the outlaws who were the mediators of such transactions. That is probably why Eski Foça was also often referred to as Karaca Foça, karaca meaning ‘a nest of pirates’.17 Piracy sometimes meant trouble for local producers because of raids but it was also advantageous as long as the pirates or smugglers paid more than Ottoman law would allow. Pirates sold the goods to European traders, especially in places like Foçateyn where islets and islands close to the mainland provided both shelter and screening from the watchful eye of the Ottoman authorities. Piracy and smuggling remained a reality of the county of Foçateyn and of Western Anatolia until the end of the Empire.

People from places like Foçateyn responded to the provisionist policies of the Ottoman centre in ways other than piracy as well. Bribing officials who were responsible for overseeing commerce and fraud was also a tactic employed by local producers and traders. Daniel Goffman has noted that there were many cases in which the Ottoman centre discovered practices conflicting with its economic policies, whereupon it acted to counter them and this invoked a counter-response by producers and dealers. Ottoman subjects in the region actively opposed the imposition of a command economy and that struggle became a defining characteristic of the region's relations with the Porte in Istanbul. For instance in 1582, Jews, Christians and ‘infidel’ foreign wine producers and dealers exhausted the grapes of the Foçateyn region for wine production. As a result, in 1584 it was reported that there were no grapes left for consumption, drying and non-alcoholic beverages (like sirke and şıra) around Yeni Foça and Eski Foça.18 At the end of the sixteenth century, the Ottoman centre became aware of this divergence in the course of trade and attempted to take preventative measures. As a result, in the winter of 1593–4, each ship that was loaded with grapes, almonds, figs and other fruits destined for Istanbul had to have a guard on board from Eski Foça. Furthermore, the castle guards in places like Foçateyn began searching farms for secret stocks of goods that had been stocked in anticipation of better prices. Preventative as it may sound, that method seems to have failed since the guards cooperated with the smugglers.19

Figure 1.1 In this well-known map (Kitab-ı Bahriye) created by Piri Reis in 1525, Eski Foça is referred to as Karaca Foça probably because of the presence of large numbers of pirates. Source: The Walters Art Museum Digital Publication, www.thewalters.org.

The provisionist Ottoman economic structure resulted in a pattern of struggles between ‘the capital's orchard’20 and the Porte in Istanbul. The Ottoman centre constantly tried to oversee and control supply and prices in the domestic market whereas producers and traders in Western Anatolia,21 including those in Foçateyn, tried to avoid the limits of such a command economy. The production and distribution of grapes is one striking example of how that was realized, especially as they were consumed extensively by all levels of society.22 However, Western Anatolian producers were not able to make the best of the productive advantage they had with grapes because they provided most of the fruit needed by the capital at fixed prices.

Incorporation into global capitalism came onto the scene in such an environment and that is why local producers and traders easily adapted to the eventual legalization of the ‘leaks’ by which they sold their goods on European markets. Capitulary arrangements with European states slowly but surely established a pattern in which piracy and smuggling were no longer as necessary since the hold of the Ottoman centre on the Western Anatolian economy was compromised. The Ottoman centre was never in full control but the eighteenth century witnessed the development of more ‘leaks’ in the provisionism of the Empire. The domestic e...