![]()

1

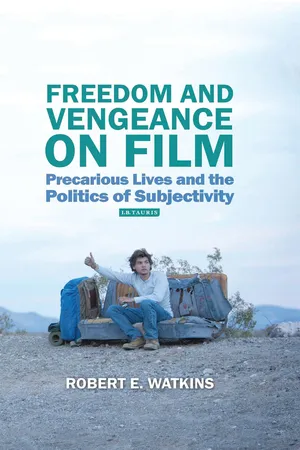

Opting Out: Into the Wild and the Fantasy of Liberal Independence

Society, you’re a crazy breed, I hope you’re not lonely without me.

(Eddie Vedder, “Society,” from Into the Wild soundtrack)

The ideal of liberal individualism still exerts a powerful hold on the American political and cultural imagination. That influence is evident in the popularity of continued academic debates in and around liberalism as well as neo-Walden-esque representations of liberal individuals such as Into the Wild, both the book by Jon Krakauer and the film by Sean Penn. There are a multitude of theories, representations, and practices that contribute to the (re)production and circulation of ideas of what liberal subjectivity is as well as the possibilities open to it in contemporary America. Yet there is a particularly persistent strain of critical liberal individualism found not only in Into the Wild but also in other contemporary works such as Elizabeth Gilbert’s book The Last American Man, Werner Herzog’s film Grizzly Man, and most recently Cheryl Strayed’s memoir Wild and the film based upon it.1 The heroes and heroines of these stories are held up for their courage in transgressing the norms of existing society in order to “return” to nature and achieve a purer, more authentic freedom.

The roots of this strain of critical individualism extend back at least to the middle of the nineteenth century, to the key works of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden (1854) and John Stuart Mill’s famous essay On Liberty (1859). The latter is particularly influential for the way that it draws inspiration from Romanticism to paint a vivid and inspiring, yet radically individual, picture of liberty. Mill’s intoxicating, romanticized liberalism offers a dazzling representation of sovereign individuality, one opposed not only to conformity but to what he refers to as “the despotism of custom.”2 Fuelled by the rejection of customary society limned by Mill, popular stories such as Into the Wild participate in a long-running cultural and political imaginary that, under the aegis of liberal freedom, directs social and political critique not only into the cultivation of a non-conformist individualism but often into a radical refusal of existing society and custom.

As enthralling and popular as these expressions of liberal individuality may be, such texts can, however, work to re-inscribe a seductively misleading representation of freedom and individuality, bearing more than a trace of an impossible autonomy. Such representations portray the liberal individual as starkly de-contextualized and free of power insofar as they downplay the necessary links between individual and community and urge escape over negotiation, refusal over amendment. By contrast, a less atomistic representation of individual liberty might acknowledge that individuals are always exercising freedom within unchosen contexts. Such is the view captured in Karl Marx’s famous lines from the Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly found, given, and transmitted from the past.”3 Like later post-structuralist thinkers such as Michel Foucault, Marx here draws our attention to the unchosen context(s) within which individual choices are made, recognizing the reality of situated subjectivity and interdependence rather than indulging in an atomistic fantasy of independence. A further implication of Marx’s formulation is that a simple and radical refusal of circumstances (social, political, cultural, historical, discursive, and so on) is not possible either, meaning that our actions are always situated – or circumstanced, if you will. Yet, Into the Wild, the film especially, offers a dramatic and misleading glorification of refusal, as if circumstance and power can simply be willed away.

In this chapter, I will bring the post-structural critique of the subject and the insights of productive power to bear on this popular representation of American individualism in order to reveal the limits of liberal individualism – specifically, tracking both the confirmation and subversion of liberal ideals in the film Into the Wild. What this simultaneous confirming subversion amounts to is a forceful, if unintended, critique of liberal individualism. Through a close reading of the film together with key texts in liberal theory and post-structuralist theory, this chapter reveals the extent to which the liberal individual – even the most atomistic one who seems most free, living in the woods alone and apart from society – is still a part of society and thus a subject, like others, who is always already acting in unchosen contexts that precede and exceed him or her.

Why, from the perspective of political theory, study popular culture in general, and this story in particular? For at least a couple of reasons drawn from the emergent discipline of cultural studies. Firstly, work at the interface of political theory and cultural studies can serve to contextualize political questions generally and issues of liberal individuality in particular. As Jodi Dean has noted, “Importantly for politics in the information age, contextualization enables political and cultural analyses to take de-politicization seriously, to address the means through which spaces, issues, identities, and events are taken out of political circulation or are blocked from the agenda.”4 The critical issue of de-politiciziation is particularly important with Into the Wild, for its story offers what many see as an admirable representation of critical individuality in the figure of Chris McCandless, but it is one that sanctions depoliticizing practices in the name of a radical Romantic individualism. Secondly, popular culture constitutes a significant field of power relations, within which subjectivity is forged. Scholars Jeffrey Nealon and Susan Searls Giroux summarize the methodological insights of politically informed cultural studies when they write that “one of the most crucial reasons to study popular culture is not so much to learn from it but to examine how it teaches us certain things.” We learn much from popular culture in ways both conscious and unconscious. Specifically, for instance, we learn “how to be subjects, or how to be certain types of subjects” (emphasis original).5 That is to say, we learn what kinds of subjectivities and identities are acceptable and unacceptable, normative and transgressive. Into the Wild is no exception to this learning process, for it makes certain kinds of pedagogical claims about how to be a subject in liberal society and about the expectations of, and possibilities open to, the liberal subject. In other words, situating Into the Wild in these larger discursive formations reminds us what the film itself seems to forget – namely, that freedom of choice itself is exercised in an unchosen context, such that “the choices we appear to make have already been made for us.”6

Freedom and Power: Complicating the Liberal Subject

Before turning to a closer examination of Into the Wild’s representation of liberal individuality, let us first consider how liberalism has traditionally understood the individual and how key developments from Friedrich Nietzsche to Michel Foucault have complicated that understanding in light of unchosen contexts and productive power. For the last 20-plus years, liberals such as Richard Flathman and kindred thinkers such as Anne Norton working at the interface of liberalism and post-structuralism have sought to ameliorate the dangers of liberal atomism by infusing our understanding of liberalism with a greater attention to the power of context and the context of power, gleaned from the insights of Foucault’s re-conceptualization of power as productive rather than simply repressive.7 Attending to the constraints given in those unchosen contexts wherein subjects exercise their liberal freedom, these theorists have unsettled the representation of individual liberty as pure refusal by folding negotiation, acceptance, and amendment into the practices of the liberal subject. Such sophisticated theoretical efforts to complicate individual liberty must, however, compete in the popular imagination with comparatively simple representations of liberal individualism, such as that of Into the Wild, which tend to over-emphasize the idealistic desire for the new and for independence at the expense of a real reckoning with the inescapability of power that necessitates negotiation by foreclosing the fantasy of escape.

“Liberalism” is a famously capacious philosophy and discourse; therefore, let me specify the particular liberalism that I have in mind. The liberalism that draws our focus here is one that occupies a central place not just in the political life of the US but also in its cultural imagination. It is embodied in the seemingly autonomous individual’s willingness to cast off the old in search of the new. As such, it is rooted in what poet and art critic Peter Schjeldhal has called “the habit of freedom” that, among other things, informs “nearly all the best American art and literature [which] is about departing, setting off, getting rid of entanglements, breaking loyalties, killing the father.”8 Such a liberalism is deeply individualistic, informed by the discourse and practices of individual rights and freedoms as well as recurrent tropes of individualism and independence, from the Western pioneers to the solitary naturalist to the innovative entrepreneur. Through its many cultural and political manifestations, this vision of liberty has become something approaching a taken-for-granted “second nature” for Americans. As Anne Norton argues in her study of liberal theory and American popular culture, Republic of Signs, “Liberalism has become the common sense of the American people, a set of principles unconsciously adhered to, a set of conventions so deeply held that they appear (when they appear at all) to be no more than common sense.”9 Such an exercise of liberal freedom prizes the ease of escape over the difficulty of endurance and negotiation.

There are at least two central components to this American liberal common sense, and broadly speaking they concern freedom, subjectivity, and power. The first is an individualistic sense of freedom, a kind of Romantic individualism that conflates individual freedom with freedom from the determinations of context and freedom from others, rather than a freedom with others or a freedom within context and power. Owing much to John Stuart Mill, this component is often criticized as atomism, as if individuals were unattached atoms floating free, and thus points toward liberalism’s problematic understanding of the subject (more on this below). The second component is a nearly innate suspicion of government in particular and power more generally. This suspicion is infused with a binary understanding of the relationship of freedom and power and often takes the form of a conflation of government with power, such that only the government is perceived as a troubling source of power. On this view, escaping government’s reach becomes synonymous with escaping power itself. This aspect of liberalism owes much to John Locke, whom political theorist Sheldon Wolin says holds a “tough-minded view of power [that] is interesting for the way it identifies power with physical coercion […] The identification of government with coercion became part of the liberal outlook.”10

By contrast, Foucault’s influential insights into the productive mode of power – whereby power does not just “say no” but also “produces things […] induces pleasure, forms knowledge, produces discourse”11 – challenge this stark opposition by highlighting the inescapability of power, its distribution throughout society, and the persistence of freedom within power. Indeed, Foucault deconstructs the opposition of freedom and power at the heart of liberalism, claiming that “power relations are possible only insofar as the subjects are free,” and further that “if there are relations of power in every social field, this is because there is freedom everywhere.”12 Whereas liberalism holds a stark, zero-sum view of this relationship, seeing freedom where power is absent and power where freedom is absent, Foucault sees power and freedom as inseparable, where the one is the condition for the other. Foucault challenges liberalism’s characteristic Lockean suspicion of government by asserting instead that “power relations are rooted deep in the social nexus, not a supplementary structure over and above ‘society’ whose radical effacement one could dream of […] A society without power relations can only be an abstraction.”13 And yet, the aspiration to a space free from power is exactly what is offered by the representation of Chris McCandless in the film Into the Wild.

The kind of liberalism that Into the Wild’s McCandless enacts and represents owes much to the Romantic, individualist liberalism of John Stuart Mill, who was self-consciously inspired by Romantic thinkers such as Wilhem von Humboldt and Romantic poets such as Lord Byron. There are two telling influences from Romanticism in both Mill’s liberalism and the film: (1) the opposition of individual to society; and (2) the privileging of impulse and feeling over reason. For instance, the film version of Into the Wild opens with a full-screen quotation from Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: “There is a pleasure in the pathless woods; / There is a rapture on the lonely shore; / There is society, where none intrudes, / By the deep sea, and music is its roar: / I love not man the less, but nature more.” This quotation, from perhaps the most famous Romantic poet, appears at the very start of the film before any action happens on screen. The deployment of this quotation at the opening of the film positions the audience to interpret the coming story in starkly individualistic and asocial terms (“There is society, where none intrudes”), mobilizing a familiar trope that pairs a deep suspicion of contaminated society with a solitary embrace of pure nature. As we will see, Mill deploys the very same stark opposition between individual and social context. Thus, the film is already positioning its protagonist, Chris McCandless, as representing a liberalism of will, desire, and refusal. Additionally, the privileging of emotion and feeling over reason is another element of Romanticism that attracts Mill and finds expression in the McCandless story, especially the film version. Mill’s contention that “desires and impulses are as much a part of a perfect human being as beliefs and restraints”14 resonates with this feature of Romanticism, as does Mill’s rejection of mechanical in favour of arboreal imagery for thinking about human nature (more on this imagery below). Later in the film, McCandless in voice-over recites Leo Tolstoy but echoes Mill when he says, “If we admit that human life can be ruled by reason, the possibility of life is destroyed.” In depreciating reason in the service of individual freedom, McCandless’ own self-conception resonates with Norton’s description of a “Liberalism [that] desires not the boundary but what lies beyond it. In that desire, will triumphs over rationality.”15 Into the Wild represents a particular form of liberal individuality as an object of will and desire, one in which individuality is constructed as an escape from troubling social influences, from subjection to the ordinary norms of American suburban life. The liberalism that the film itself offers up for admiration is therefore not so much deliberative and rational, or concerned with rights and procedures, as it is intuitive, Romantic, and impulsive. Into the Wild showcases a vision of freedom as self-making, apart from society and away from power. Such a liberalism is as much a cultural force and an indirect influence on politics (depoliticizing though it may be) as any formal political liberalism.

John Stuart Mill, in particular, infuses the theory and practice of liberty with a naturalistic and individualistic ethos. Mill’s ...