eBook - ePub

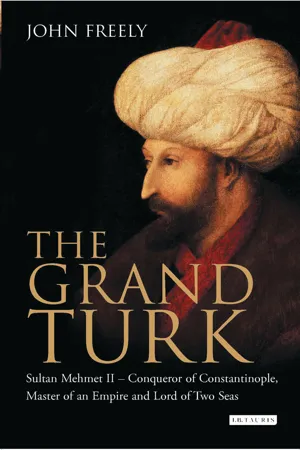

The Grand Turk

Sultan Mehmet II - Conqueror of Constantinople, Master of an Empire and Lord of Two Seas

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Grand Turk

Sultan Mehmet II - Conqueror of Constantinople, Master of an Empire and Lord of Two Seas

About this book

Sultan Mehmet II, the Grand Turk, known to his countrymen as Fatih, 'the Conqueror', and to much of Europe as 'the present Terror of the World', was once the most feared and powerful ruler in the world. The seventh of his line to rule the Ottoman Turks, Mehmet was barely 21 when he conquered Byzantine Constantinople, which became Istanbul and the capital of his mighty empire. Mehmet reigned for 30 years, during which time his armies extended the borders of his empire halfway across Asia Minor and as far into Europe as Hungary and Italy. Three popes called for crusades against him as Christian Europe came face to face with a new Muslim empire.Mehmet himself was an enigmatic figure. Revered by the Turks and seen as a cruel and brutal tyrant by the west, he was a brilliant military leader but also a renaissance prince who had in his court Persian and Turkish poets, Arab and Greek astronomers and Italian scholars and artists.

In this, the first biography of Mehmet for 30 years, John Freely vividly brings to life the world in which Mehmet lived and illuminates the man behind the myths, a figure who dominated both East and West from his palace above the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, where an inscription still hails him as, 'Sultan of the two seas, shadow of God in the two worlds, God's servant between the two horizons, hero of the water and the land, conqueror of the stronghold of Constantinople."

In this, the first biography of Mehmet for 30 years, John Freely vividly brings to life the world in which Mehmet lived and illuminates the man behind the myths, a figure who dominated both East and West from his palace above the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, where an inscription still hails him as, 'Sultan of the two seas, shadow of God in the two worlds, God's servant between the two horizons, hero of the water and the land, conqueror of the stronghold of Constantinople."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Grand Turk by John Freely in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | The Sons of Osman |

Constantine the Great changed the course of history in AD 330, when he shifted his capital from Italy to the Greek city of Byzantium on the Bosphorus, renaming it New Rome, though it came to be called Constantinople.

Constantine’s immediate successors established Christianity as the state religion of the empire, and during the next two centuries Greek replaced Latin as the official language. This gave rise to what later historians called the Byzantine Empire, the Hellenised Christian continuation of the Roman Empire, which took its name from the ancient city of Byzantium.

The Byzantine Empire reached its peak under Justinian (r. 527–65), whose realm extended almost entirely around the Mediterranean, including all of Italy, the Balkans, Asia Minor and the Middle East. During the next five centuries the empire was under attack on all sides, but as late as the mid-eleventh century it still controlled all of Asia Minor and the Balkans as well as southern Italy. But then in 1071 the emperor Romanus IV Diogenes was defeated by the Seljuk Turks under Sultan Alp Arslan at a battle near Manzikert in eastern Anatolia, as Asia Minor is now more generally known, while that same year the Normans took the last remaining Byzantine possessions in Italy.

After their victory at Manzikert the Turks overran Anatolia, though the Byzantines, with the help of the army of the First Crusade, reconquered the western part of Asia Minor and the coastal areas along the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. The central and eastern parts of Anatolia became part of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, the Turkish word for Greeks of the Byzantine Empire, whose territory they had conquered.

The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum lasted from the second half of the eleventh century until the beginning of the fourteenth century. At their peak, in the first quarter of the thirteenth century, the Seljuks controlled all of Anatolia except for Bithynia, the north-westernmost part of Asia Minor, which was virtually all that remained of the Byzantine Empire in Asia, while the Greek empire of the Comneni dynasty ruled the eastern Black Sea region from their capital at Trebizond.

The Byzantine Empire was almost destroyed during the Fourth Crusade, when Latin troops and the Venetian navy captured and sacked Constantinople in 1204. Constantinople then became capital of a Latin kingdom called Roumania, which lasted until 1261, when the city was recaptured by the Greeks under Michael VIII Palaeologus, who had survived in exile in the Bithynian city of Nicaea.

But the revived Byzantine Empire was just a small fragment of what it had been in its prime, and by the beginning of the fifteenth century it comprised little more than Bithynia, part of the Peloponnesos, and Thrace, the south-easternmost region of the Balkans up to the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus, the historic straits that separate Europe and Asia.

The Seljuks declined rapidly after they were defeated by the Mongols in 1246, and at the beginning of the following century their sultanate came to an end, with their former territory divided among a dozen or so Turkish emirates known as beyliks. The smallest and least significant of these beyliks was that of the Osmanlı, the ‘sons of Osman’, the Turkish name for the followers of Osman Gazi, whose last name means ‘warrior for the Islamic faith’. Osman was known in English as Othman, and his dynasty came to be called the Ottomans. He was the son of Ertuğrul, leader of a tribe of Oğuz Turks who at the end of the thirteenth century settled as vassals of the Seljuk sultan around Söğüt, a small town in the hills of Bithynia, just east of the Byzantine cities of Nicomedia, Nicaea and Prusa. The humble origin of the Osmanlı is described by Richard Knolles in The Generall Historie of the Turkes (1609–10), one of the first works in English on the Ottomans:

Thus is Ertogrul, the Oguzian Turk, with his homely heardsmen, become a petty lord of a countrey village, and in good favour with the Sultan, whose followers, as sturdy heardsmen with their families, lived in Winter with him in Söğüt, but in Summer in tents with their cattle upon the mountains. Having thus lived certain yeares, and brought great peace with his neighbours, as well the Christians as the Turks... Ertogrul kept himself close in his house in Söğüt, as well contented there as with a kingdom.

The only contemporary Byzantine reference to Osman Gazi is by the chronicler George Pachymeres. According to Pachymeres, the emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus (r. 1282–1328) sent a detachment of 2,000 men under a commander named Muzalon to drive back a force of 5,000 Turkish warriors under Osman (whom he calls Atman), who had encroached upon Byzantine territory. But Osman forced Muzalon to retreat, which attracted other Turkish warriors to join up with him, in the spirit of gaza, or holy war against the infidel, attracted also by the prospects of plunder.

With these reinforcements Osman defeated Muzalon in 1302 in a pitched battle at Baphaeus, near Nicomedia. Soon afterwards Osman captured the Byzantine town of Belakoma, Turkish Bilecik, after which he laid siege to Nicaea, whose defence walls were the most formidable fortifications in Bithynia. He then went on to pillage the surrounding countryside, causing a mass exodus of rural Greeks from Bithynia to Constantinople, after which he captured a number of unfortified towns in the region.

Osman Gazi died in 1324 and was succeeded by his son Orhan Gazi, the first Ottoman ruler to use the title of sultan, as he is referred to in an inscription. Two years after his succession Orhan captured Prusa, Turkish Bursa, which became the first Ottoman capital. He then renewed the siege of Nicaea, and in 1329 the emperor Andronicus III Palaeologus (r. 1328–41) personally led an expedition to relieve the city. Orhan routed the Byzantine army at the Battle of Pelekanon, in which the emperor was wounded, leaving his commander John Cantacuzenus to lead the defeated army back to Constantinople.

Nicaea, known to the Turks as Iznik, was finally forced to surrender in 1331, after which Orhan went on to besiege Nicomedia, Turkish Izmit, which finally surrendered six years later. That virtually completed the Ottoman conquest of Bithynia, by which time Orhan had also absorbed the neighbouring Karası beylik to the south, so that the Ottomans now controlled all of westernmost Anatolia east of the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles.

Andronicus III died on 15 June 1341 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son John V Palaeologus. John Cantacuzenus was appointed regent, and later that year his supporters proclaimed him emperor. This began a civil war that lasted until 8 February 1347, when Cantacuzenus was crowned as John VI, ruling as senior co-emperor with John V.

Meanwhile, Orhan had signed a peace treaty in 1346 with Cantacuzenus. Cantacuzenus sealed the treaty by giving his daughter Theodora in marriage to Orhan, who wed the princess in a festive ceremony at Selymbria, in Thrace on the European shore of the Marmara forty miles west of Constantinople. Shortly after Cantacuzenus was crowned as senior co-emperor in 1347 Orhan came to meet him at Scutari, on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus opposite Constantinople. According to the chronicle that Cantacuzenus later wrote, he and his entourage crossed the Bosphorus in galleys to meet Orhan and his attendants, ‘and the two amused themselves for a number of days hunting and feasting’.

Cantacuzenus ruled as co-emperor until 10 December 1354, when he was deposed by the supporters of John V, after which he retired as a monk and wrote his chronicle, the Historia, one of the most important sources for the last century of Byzantine history and the rise of the Ottoman Turks.

Throughout his reign Cantacuzenus honoured the alliance he had made with Orhan. During that time Orhan thrice sent his son Süleyman with Turkish troops to aid Cantacuzenus on campaigns in Thrace. On the third of these campaigns, in 1352, Süleyman occupied a fortress on the Dardanelles called Tzympe, which he refused to return until Cantacuzenus promised to pay him 1,000 gold pieces. The emperor paid the money and Süleyman prepared to return the fortress to him, but then, on 2 March 1354, the situation changed when an earthquake destroyed the walls of Gallipoli and other towns on the European shore of the Dardanelles, which were abandoned by their Greek inhabitants. Süleyman took advantage of the disaster to occupy the towns with his troops, restoring the walls of Gallipoli in the process. A Florentine account of the earthquake and its aftermath says that the Turks then ‘received a great army of their people and laid siege to Constantinople’, but after they were unable to capture it ‘they attacked the towns and pillaged the countryside’. Cantacuzenus demanded that Gallipoli and the other towns be returned, but Süleyman insisted that he had not conquered them by force but simply occupied their abandoned ruins. Thus the Ottomans established their first permanent foothold in Europe, which Orhan was able to use as a base to make further conquests in Thrace.

Orhan also extended his territory eastward in Anatolia, as evidenced by a note in the Historia of Cantacuzenus, saying that in the summer of 1354 Süleyman captured Ancyra (Ankara), which had belonged to the Eretnid beylik, thus adding to the Ottoman realm a city destined to be the capital of the modern Republic of Turkey.

A Turkish source says that Süleyman captured the Thracian towns of Malkara, Ipsala and Vize. This would have been prior to the summer of 1357, when Süleyman was killed when he was thrown from his horse while hunting.

Orhan Gazi died in 1362 and was succeeded by his son Murat, who had been campaigning in Thrace. In 1369 Murat captured the Byzantine city of Adrianople, which as Edirne soon became the Ottoman capital, replacing Bursa. Murat used Edirne as a base to campaign ever deeper into the Balkans, and during the next two decades his raids took him into Greece, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Albania, Serbia, Bosnia and Wallachia. On 26 September 1371 Murat annihilated a Serbian army at the Battle of the Maritza, opening up the Balkans to the advancing Ottomans. By 1376 Bulgaria recognised Ottoman suzerainty, although twelve years later they tried to shed their vassal ties, only provoking a major Turkish attack that cost them more territory.

At the same time, Murat’s forces expanded the Ottoman domains eastward and southward into Anatolia, conquering the Germiyan, Hamidid and Teke beyliks, the latter conquest including the Mediterranean port of Antalya.

Murat’s army occupied Thessalonica in 1387 after a four-year siege, by which time the Ottomans controlled all of southern Macedonia. His capture of Niš in 1385 brought him into conflict with Prince Lazar of Serbia, who organised a Serbian–Kosovan–Bosnian alliance against the Turks. Four years later Murat again invaded Serbia, opposed by Lazar and his allies, who included King Trvtko I of Bosnia.

The two armies clashed on 15 June 1389 near Pristina at Kosovo Polje, the ‘Field of Blackbirds’, where in a four-hour battle the Turks were victorious over the Christian allies. At the climax of the battle Murat was killed by a Serbian nobleman who had feigned surrender. Lazar was captured and beheaded by Murat’s son Beyazit, who then slaughtered all the other Christian captives, including most of the noblemen of Serbia. Serbia never recovered from the catastrophe, and thenceforth it became a vassal of the Ottomans, who were now firmly established in the Balkans.

Soon afterwards Beyazit murdered his own brother Yakup to succeed to the throne, the first instance of fratricide in Ottoman history. Beyazit came to be known as Yıldırım, or Lightning, from the speed with which he moved his army, campaigning both in Europe and Asia, where he extended his domains deep into Anatolia.

Beyazit’s army included an elite infantry corps called yeniçeri, meaning ‘new force’, which in the West came to be known as the janissaries. This corps had first been formed by Sultan Murat from prisoners of war taken in his Balkan campaigns. Beyazit institutionalised the janissary corps by a periodic levy of Christian youths called the devşirme, first in the Balkans and later in Anatolia as well. Those taken in the devşirme were forced to convert to Islam and then trained for service in the military, the most talented rising to the highest ranks in the army and the Ottoman administration, including that of grand vezir, the sultan’s first minister. They were trained to be loyal only to the sultan, and since they were not allowed to marry they had no private lives outside the janissary corps. Thus they developed an intense esprit de corps, and were by far the most effective unit in the Ottoman armed forces.

During the winter of 1391–2 Beyazit launched major attacks by his akinci, or irregular light cavalry, against Greece, Macedonia and Albania. Early in 1392 Ottoman forces captured Skopje, and most of Serbia accepted Ottoman suzerainty. Then in July 1393 Beyazit captured Turnovo, capital of the Bulgarian Empire, after which Bulgaria became an Ottoman vassal, remaining under Turkish rule for nearly 500 years.

Beyazit laid siege to Constantinople in May 1394, erecting a fortress that came to be known as Anadolu Hisarı on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus at its narrowest stretch. While the siege continued Beyazit led his army into Wallachia, capturing Nicopolis on the Danube in 1395.

King Sigismund of Hungary appealed for a crusade against the Turks, and in July 1396 an army of nearly 100,000 assembled in Buda under his leadership.

The Christian army comprised contingents from Hungary, Wallachia, Germany, Poland, Italy, France, Spain and England, while its fleet had ships contributed by Genoa, Venice and the Knights of St John on Rhodes. Sigismund led his force down the Danube to Nicopolis, where he put the Turkish-occupied fortress under siege. Two days later Beyazit arrived with an army of 200,000, and on 25 September 1396 he defeated the crusaders at Nicopolis and executed most of the Christian captives, though Sigismund managed to escape.

Beyazit then renewed his siege of Constantinople, where the Greeks had been reinforced by 1,200 troops sent by Charles VI of France under Marshal Boucicault, a survivor of the Battle of Nicopolis. The marshal realised that his force was far too small, and so he persuaded the emperor Manuel II to go with him to France so that he could present his case to King Charles. Manuel went on to England, where on 21 December 1400 he was escorted into London by King Henry IV, though he received nothing but pity, returning to Constantinople empty-handed early in 1403.

But by then the situation had completely changed, for the previous spring Beyazit had lifted his siege of the city and rushed his forces back to Anatolia, which had been invaded by a Mongol horde led by Tamerlane. The two armies collided on 28 July 1402 near Ankara, where the Mongols routed the Turks, many of whom deserted at the outset of the battle. Beyazit himself was taken prisoner, and soon afterwards he died in captivity, tradition holding that he had been penned up in a cage by Tamerlane.

Five of Beyazit’s sons – Süleyman, Mustafa, Musa, Isa and Mehmet – also fought in the battle. Mustafa and Musa were captured by Tamerlane, while the other three escaped. Musa was eventually freed by Tamerlane, while Mustafa apparently died in captivity, though a pretender known as Düzme (False) Mustafa later appeared to claim the throne. Beyazit’s youngest son, Yusuf, escaped to Constantinople, where he converted to Christianity before he died of the plague in 1417.

The Ottoman state was almost destroyed by the catastrophe at Ankara. After his victory Tamerlane reinstated the emirs of the Anatolian beyliks that had fallen to the Ottomans, while in the Balkans the Christian rulers who had been Beyazit’s vassals regained their independence. The next eleven years were a period of chaos, as Beyazit’s surviving sons fought one another in a war of succession, at the same time doing battle with their Turkish and Christian opponents. The struggle was finally won by Mehmet, who on 5 July 1413 defeated and killed his brother Musa at a battle in Bulgaria, their brothers Süleyman and Isa having died earlier in the war of succession.

Mehmet ruled for eight years, virtually all of which he spent in war, striving to re-establish Ottoman rule in Anatolia and the Balkans. His last campaign was a raid across the Danube into Wallachia in 1421, shortly after which he died following a fall from his horse. He was succeeded by his son Murat II, who although only seventeen was already a seasoned warrior, having fought in at least two battles during his father’s war of succession.

At the outset of Murat’s reign he had to fight two wars of succession, first against the pretender Düzme Mustafa and then against his own younger brother, also named Mustafa, both of whom he defeated and killed. Both of the pretenders had been supported by the emperor Manuel II, and so after Murat put them down he sought to take his revenge on the emperor, putting Constantinople under siege on 20 June 1422. But the Byzantine capital was too strongly fortified for him to conquer, and at the end of the summer he decided to abandon the siege and withdraw.

Manuel suffered a critical stroke during the siege, whereupon his son John was made regent. Manuel died on 21 July 1425, and on that same day his son succeeded him as John VIII.

Mu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Dedication page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Turkish Spelling and Pronunciation

- List of Maps and Illustrations

- Prologue: Portrait of a Sultan

- 1 The Sons of Osman

- 2 The Boy Sultan

- 3 The Conquest of Constantinople

- 4 Istanbul, Capital of the Ottoman Empire

- 5 Europe in Terror

- 6 War with Venice

- 7 The House of Felicity

- 8 A Renaissance Court in Istanbul

- 9 The Conquest of Negroponte

- 10 Victory over the White Sheep

- 11 Conquest of the Crimea and Albania

- 12 The Siege of Rhodes

- 13 The Capture of Otranto

- 14 Death of the Conqueror

- 15 The Sons of the Conqueror

- 16 The Tide of Conquest Turns

- 17 The Conqueror’s City

- Notes

- Glossary

- The Ottoman Dynasty

- Bibliography