![]()

PART ONE

DICKIE MOUNTBATTEN, CONSUL, COURTIER, CHARMER, AND CHANCER

![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

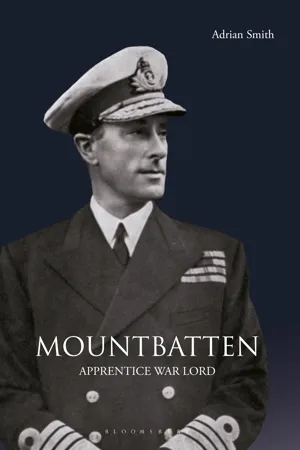

The imperious Mountbatten: at home in the empire

This is a story that begins and ends with an empire tested by war. When His Serene Highness Prince Louis of Battenberg was born at Frogmore House on 25 June 1900 the army of his great-grandmother, the Queen Emperor, was far from home and struggling to maintain imperial authority. Nevertheless, however costly the final outcome, and inauspicious the long-term prospect, Boer power in South Africa was finally contained. Forty-three years later, when Acting Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten arrived in the Far East as the Allies’ Supreme Commander South East Asia, a restoration of the imperial status quo appeared a remote prospect: Japanese forces had usurped Britain’s colonial authority in every corner of southern Asia, besieging India and threatening the very survival of the Raj. Remarkably, Mountbatten and his outstanding field commander, Bill Slim, transformed a punch-drunk empire’s demoralized and defeatist army into a fighting force capable of facing up to and defeating a formidable enemy. The 14th Army that fought its way to Rangoon was in every respect Slim’s creation, but tempering Mountbatten’s exaggerated claims for its success need not entail a total dismissal of his role in restoring Britain’s credibility as a military power east of Suez. Yet, for all the heroics of the ‘Forgotten Army’, after the Second World War the challenge was simply too great: the ferocity of nationalist sentiment in the Indian sub-continent and beyond signalled the eclipse of European hegemony.

In some cases, such as the Dutch East Indies, the end came soon. In others, for example, Malaya, several years would pass before the flag was finally brought down. Either way, the writing was on the wall.1 No wonder the Americans mockingly christened SEAC ‘Save England’s Asian Colonies’. Mountbatten’s direct contribution to the withdrawal from empire – from tension with France and Holland once the war in the Far East was over, through to Indian independence and partition two years later – lies beyond the focus of this book. The present volume concludes with Churchill increasingly fearful that imperial decline was the inevitable price of grand alliance.

Nevertheless, this is a tale told against the backdrop of a liberal-imperialism which, even with the departure from Delhi, still envisaged slimmed-down survival. This was after all an era when a bankrupt yet victorious Britain could briefly enjoy the moral high ground. That smeared window of opportunity – for a British Commonwealth that in reality could never be – lasted from Ernie Bevin’s first musings on the global altruism of a social democratic ‘Third Force’ to Anthony Eden’s last hurrah on the banks of the Suez Canal. These were the years when the Colonial Office’s never very convincing optimism collapsed in the face of ground nut fiascos and ferociously-fought ‘emergencies’.

The Second World War clearly accelerated this janus-like surrender of power – bloody and painful in the field, yet generating remarkably few tensions back home. Nevertheless, despite more prescient commentators’ early mutterings of disquiet, the British Empire still appeared the major global force throughout the first half of Mountbatten’s life. This was most obvious in the 1920s, at a time when ‘imperial over stretch’ was no more than a dark cloud on a very distant horizon. The Anglicised Lord Louis had spent his adolescent years on active service, protecting the imperial heartland from the Teutonic threat across the North Sea. In his early twenties he accompanied the Prince of Wales on flag-flying tours of cousin David’s far-flung future domains. Resuming his naval career, Mountbatten’s late twenties were focused upon technical proficiency in communications, and postings to that most visible symbol of extended power, the Mediterranean Fleet. Edwina Ashley, his glamorous and wealthy wife, had been acquired courtesy of a courtship that climaxed, most appropriately, with a proposal of marriage in the Viceregal Lodge. In the course of the following decade the tyro destroyer commander swapped deck for desk, lobbying for the restoration of the Fleet Air Arm and calculating the full impact of Axis air power on an overstretched surface fleet. His flotilla scattered or sunk, in May 1941 Mountbatten lost his own ship as a shredded imperial army surrendered Crete in a maelstrom of heroism and hysteria. Combined Operations would at last see the Empire strike back, but such an ambition could only be achieved at the cost of Canada’s finest. A much-criticised chief of staff always defended Dieppe as a costly but necessary first step towards D-Day, that almighty but all too brief final display of British military might. By then operational planning of an equally impressive feat of arms – the recovery of Burma – was well advanced, with the supreme commander ultimately swapping the security of Ceylon for the more salubrious comforts of a liberated Singapore.

From the autumn of 1943 Mountbatten found himself a pro-consul, charged with hurling the barbarians back and reclaiming the distant territories of a great yet fading empire. A trusted general rebuilt the legions and recaptured the eagles, but final victory relied upon the military might of a new and increasingly assertive ally – an emergent imperial power still stubbornly refusing to accept itself as such. Despite his relative youth (a handsome face belied encroaching middle age), Mountbatten’s three years as a war lord marked the culmination of a lengthy apprenticeship. Admittedly his ascension to supreme commander was astonishing given that as recently as the spring of 1941 he was still a relatively junior captain – command of a destroyer flotilla scarcely reflected his modest placing in the Navy List. And yet, he had been in uniform for almost the whole of his life. For all his faults, and there were many, Mountbatten’s glamorous lifestyle was rarely at the expense of his career. The obvious exception is globetrotting with the Prince of Wales, but he clearly drew a line in the sand at the conclusion of the second tour. His return home marked the re-awakening of a scarcely dormant ambition that in the ensuing years became ever more single-minded – Dickie Mountbatten was a driven man, and, while it may seem clichéd to suggest that matching his father’s achievement and becoming First Sea Lord was the prime motivation, every facet of his career suggests that here was someone with one simple objective. This book examines every aspect of that career, taking particular note of the fact that Mountbatten fought not just one but two world wars. For the first time the legacy of his experience in the Great War is fully explored, returning to inform the final part, when the book climaxes with ‘Operation Jubilee’, the second most contentious event in a career dogged by controversy: two chapters consider in detail the raid on Dieppe mounted by Combined Operations on 19 August 1942. Given the scale of Canada’s losses, perhaps no other event since Confederation has placed as great a strain on relations between Britain and her most vital imperial ally.

Figure 1.1: HRH going native in Japan with Lord Louis and ‘Fruity’ Metcalfe, April 1922

The last viceroy was, of course, far more than, in David Cannadine’s memorable phrase, the ‘imperial undertaker who never wore black’ – someone who rose to fame on the back of empire, and yet with unusual prescience sensed which way the winds of change were blowing.2 As flotilla captain, frontline commander, grand strategist, naval reformer, Whitehall moderniser, and Windsor eminence grise, for nigh on six decades he operated at the very heart of power. Almost as long as the tally of jobs he did take on is the list of posts Mountbatten claimed to have turned down: Minister of Defence in both Labour and Conservative governments, as well as several governor-generalships, including post-UDI Rhodesia. Here was someone adamant that he could do a better job running the country than Attlee.3

It’s ironic that both Clem and Harold Wilson saw Lord Louis as a safe pair of hands, as adept at handling Ian Smith as Mahatma Gandhi.4 As has been said, controversy dogged Mountbatten throughout his career; assassination at the hands of the IRA in August 1979 only momentarily silenced his critics. That Irish republicans should murder someone so synonymous with colonial concession is of course a cruel irony, especially when their victim saw reunification as ‘the only eventual solution’.5 Mountbatten’s pragmatic (for imperial apologists, wholly cynical) view of empire reflected a calculated ability to soak up and even embrace the forces of modernity: to adjust and to adapt to change, while never, however briefly, renouncing the physical security, psychological reassurance, and material comfort of tradition and privilege.6 Here was an aristocrat in an ostensibly meritocratic era, who, by dint of personality and professional training, found himself still wielding an extraordinary degree of influence. Yet in many respects Admiral of the Fleet the Earl Mountbatten of Burma was an Orléanist, protected from the harshest consequences of social revolution.7 After the war he was quick to acknowledge a new spirit of egalitarianism, albeit heavily qualified. However, in reality he was too elevated and then too old to experience any significant shifts in the tectonic plates of British society, most obviously the demise of deference.8

The Ubiquitous Mountbatten: At Home in Hampshire

Tropical kit neatly pressed, peaked cap at trademark rakish angle, sleeves rolled ready for action, the Supreme Commander South East Asia stares meaningfully across Grosvenor Square. Given that Mountbatten made so little use of public transport throughout his 79 years it’s ironic that his statue stands on the former site of the Southampton bus station. On many maps of the city the ‘square’ is not even marked, despite the tastefully disguised multi-storey car park and the gentrified corporate buildings. The setting contrasts markedly with Lord Louis’ very public presence in Whitehall. Here Franta Belsky’s severe statue stands on Horse Guards Parade, suitably adjacent to the Foreign Office – Dickie Mountbatten, anti-appeaser and last viceroy, master of both gun boat and diplomacy. In central London Mountbatten is only one on an avenue of heroes, a tourist-trail pantheon of leaders on air, sea and land who together led their country to victory in two world wars. The Southampton statue is in its own quiet way a shrine and a sanctuary, commissioned by a property developer in 1990 but taken over by the Burma Star Association eight years later: the original sculpture and a later memorial tablet were both unveiled by the veterans’ vice patron, Patricia, the Countess Mountbatten. Within Burma’s famous ‘forgotten’ 14th Army Mountbatten could never enjoy the loyalty and affection felt for ‘Uncle Bill’, the future Field Marshal Lord Slim. Yet – as at every stage of his career – goodwill in the ranks more than cancelled out the suspicion or even outright hostility felt by those who operated in close proximity to him; and yet remained resistant to the easy charm, the cultivated mix of relaxed manner and urgent command, and the seductive charisma of a man apparently at ease with the trappings of power and privilege. Mountbatten could of course generate fierce loyalty within the wardroom or the mess, and it would be simplistic to suggest that here was someone whom one either loved or loathed (for his biographer a day in the archives can produce a whole range of emotions, from indignation at the level of conceit through to astonishment at the scale of achievement). Whether weary ships’ companies, fledgling commandos, or revengeful Chindits, Mountbatten demonstrated a remarkable ability to surmount an enormous divide of wealth and status when dealing directly with the forces under his command. Surmounting the cynicism – including perhaps that of his immediate subordinates – he had the capacity to deliver a convincingly clear-cut, and on the whole bullshit-free, operational briefing: a rallying exhortation which would leave a lasting presence in terms of raising collective and individual morale. For this reason alone the veterans of Kohima and the Arakan treat Grosvenor Square with the same respect as remaining members of the Kelly’s mess decks view their captain’s final resting place in Romsey.

Distance breeds indifference if not disenchantment, and the passage of time has seen even as striking a monument as the Grosvenor Square statue merge in to a blurred, seemingly unchanging – and thus dimly perceived – urban landscape. Yet for those who care to register his presence Lord Mountbatten retains a permanent high profile, from Romsey to Ryde, and from Pompey to Poole. Nor should an earlier memorialisation of Edwina be forgotten, particularly in hospitals and schools. If the Broadlands estate lies at the heart of this sprawling, scarcely registered regional homage, then Southampton provides a model of civic commemoration: several offices, two university research centres, a major arterial road, a retail park, a Salvation Army refuge, and even a pub opened by the great man himself – as indeed was the building in which I write. By comparison, Admiral Jellicoe, the Grand Fleet’s commander at Jutland and a First Sea Lord actually born in the city, is rewarded with nothing grander than a blue plaque. Only the Isle of Wight, where Mountbatten proved a popular governor, can match such ubiquity. It may be the republican norm across France, the United States, and even Australia, but the naming of roads, places and buildings after politicians and military commanders is scarcely commonplace in Britain: few French towns would dare to ignore Clemenceau and De Gaulle, and yet at home Lloyd George is invisible and Churchill more likely to give his name to a major institution than a minor thoroughfare. So why is Mountbatten the exception to the rule, certainly so far as the south of England is concerned? To say that he remains closely associated with the Solent and the Test Valley goes some way to explaining why his name survives in so many varied places. Yet almost certainly it was his intimate involvement with the Royal Family which bestowed on him a unique status, even while he was still alive. The brutal nature of Mountbatten’s death further strengthened his posthumous credibility, reinforcing the case for numerous public buildings and roads to tap the last vestiges of deference and respect.

Hampshire may remain the epicentre of a fast-fading memorialisation, but recollection of Mountbatten continues to stir emotions wherever his legacy survives, most obviously in southern Asia – events marking the sixtieth anniversary of independence and partition offered a sharp reminder of critics’ readiness to demonise, and of admirers’ undiminished eagerness to applaud.9 Yet for a man so obsessed with reputation the judgement of posterity stretched far beyond parochial debate over the relevance of the Mountbatten name to the twenty-first century. If he desperately needed to be the centre of attention in life then he yearned to remain so in death.

The meticulous Mountbatten: at home in the archives

Mountbatten planned his biography in the same way that he planned his funeral. In retirement at Broadlands he and his staff ceaselessly shifted and sorted official papers and private correspondence. Even before his departure from the Ministry of Defence in 1965 a few spare hours could always be found to scrutinise the files. Here was the archival lode which his official biographer would one day mine. Sudden, tragic death brought no abrupt end to the process of collection and cataloguing; a mass of posthumous material left the family facing a fresh challenge of filtering out the trivial and dealing with the downright hostile. Mountbatten’s operating rule had been ‘when in doubt, retain’, and he was remorseless in hunting down even the most remotely relevant documents and artefacts. As for the controversial and contentious, he regularly rallied the Praetorian Guard of old comrades and trusted cronies to draft favourable briefing papers or to track down supportive evidence. Those closest to him, such as his former press attaché, Alan Campbell-Johnson, were lifelong keepers of the flame, ensuring Dickie’s case for the defence survived beyond the grave.10 Yet nearly two decades after his death even Campbell-Johnson could concede that, ‘without Edwina there to cut him down to size, his surface vanity flourished. He did a lot of damage to his own reputation in those years’.11 Sadly, Hugh Massingberd’s account of his spring 1979 interview with an indiscrete, obsessive, vainglorious ‘Polonius of the Court’ is horribly convincing.12

Mountbatten’s determination to ensure that any future researcher would recount the ‘right’ story was made that much more difficult by the introduction of the ‘Thirty Year Rule’ in 1967. Now he had to make certain any criticism of his actions that might eventually enter the public domain, for example, the Admiralty’s rather jaundiced view of his first year in command of the 5th Destroyer Flotilla, would be discredited once his own version of events, then and later, was made available to a sympathetic and open-minded nation. Thus, when judged appropriate, he would speedily respond to any slur on his reputation; but otherwise he played the long-game, certain that eventually the ‘truth’ would come out, with every course of action, big or small, seen to be necessary and correct.

Clearly the choice of authorised biographer was crucial, and Mountbatten spurned premature efforts to bestow the imprimatur, however elevated the author. After all, during and after the war a generally supportive press, encouraged from 1942 by Lord Louis’ formidable PR team, did m...