![]()

Part I: The Problem with Beauty

Chapter 1

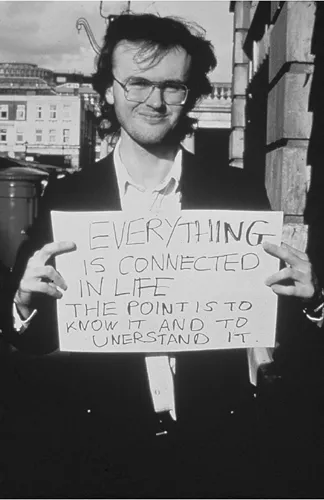

Everything Is Connected in Life

Beautiful Things in Science

When I first became interested in science and found myself in the company of scientists, I was regularly struck by their frequent use of a word that is scarcely ever heard in the arts. That word is ‘beauty’. In spite of the sheer effort required by the scientific enterprise – the fiddling with high-tech instruments, the sifting of vast amounts of data, the anxiety about grant applications, the bruising competitiveness that surrounds publication – when they talk about their work, scientists often verge on the rhapsodic. In his book Unweaving the Rainbow, Richard Dawkins challenges the view expressed in Romantic poetry that the desire to analyse the workings of the world through examining its smallest components is merely to make a ‘dull catalogue of common things’.1 On the contrary, he says, ‘The wonder of the universe and our place in it is revealed through science in ways otherwise impossible to appreciate or imagine.’ Physiologist Francis Ashcroft, whose research investigates the function of ion channels in the beta cells of the pancreas, says, ‘I am piecing together the puzzle. My aim is to see the interconnectedness of it all – how all the bits fit together to produce something gloriously new.’

In the world of science the idea that there is some kind of universal jigsaw where all the bits fit together seems to prevail. Marcus du Sautoy is working in an area of mathematics called group theory which tries to understand symmetry. He describes finding consistent mathematical patterns which form palindromes, reading the same from left to right as from right to left. ‘Knowing that a zeta function has palindromic symmetry would not be so amazing as a result in itself,’ he writes:

It’s more that it is evidence of some deep and subtle structure at the heart of my subject which I don’t yet understand. And it is showing a small bit of its beautiful head by manifesting itself in this functional equation. If I can understand this palindromic symmetry I am convinced it will go hand in hand with revealing a huge vista of structure that we are currently too blind to see.2

In the introduction to the book It Must be Beautiful: An Anthology of the Great Equations of Modern Science,3 its editor, the physicist and science writer Graham Farmelo, tells how the physicist Paul Dirac, asked in a seminar in Moscow in 1955 to summarise his philosophy, wrote on the blackboard in capital letters, ‘PHYSICAL LAWS SHOULD HAVE MATHEMATICAL BEAUTY.’ Farmelo writes:

Much like a work of art, a beautiful equation has among its attributes much more than attractiveness – it will have universality, simplicity, inevitability and an elemental power.

It is hard to believe that Farmelo and his fellow scientists inhabit the same planet as contemporary artists and the theorists whose discourse underpins their practice. Because for them the idea of simple, beautiful equations is barely conceivable. The artist’s experience of life is uncoordinated, dislocated, contingent, incomplete. ‘Art does not belong to the order of revelation,’ wrote the phenomenologist Emmanuel Levinas. It is ‘the very event of observing, a descent of night, an invasion of shadow.’4 ‘Art is magic delivered from the lie of being truth,’ declared Theodor Adorno. Knowledge itself may do little more than reflect our capacity for persistent self-delusion, Foucault claimed. Such capriciousness extends to everything we try to take account of, including science. Reality shifts, it is always conditional. A postmodernist theorist might well invert Farmelo’s axiom:

Much like a work of science, a work of art represents both more and less than a simulacrum of pleasure – it is foregrounded by the values relative to the value-maker, attests to multiple layers of possible meaning, is inevitable only in that it privileges the mores of a particular culture at a particular time in history and, within its shifting temporary context, it is ripe for continual reinterpretation and validation.

The dramatic contrast between these two visions of reality makes manifest the extreme differences in the epistemological traditions which have underpinned and separated the two cultures of science and the arts and humanities through much of the twentieth century. Fundamentally, these concern whether distinctions can be made between the act of perceiving and the object perceived. On the one side is the school of neo-realism, which posits that objects and phenomena exist in themselves and can be studied rationally and empirically, independent of one’s mental state.5 There is an immaculate universe ‘out there’. On the other side is the phenomenalist contention that one cannot distinguish between objects of knowledge and objects as one perceives them. Linguistic philosophy examines how basic epistemological words such as ‘knowledge’ and ‘perception’ are used.6 Everything is provisional. There is no room for the absolute here, let alone an absolute beauty.

There are some artists and critics who dare to use the word ‘beauty’ unenclosed by the heavy quotation marks of irony. In her 2001 book The Trouble with Beauty,7 Wendy Steiner sees beauty as a higher principle outside the boundaries of time and place, achieved through a striving for love, compassion and, especially, through the female spirit of empathy. Beauty is expressed through decorum and finesse, harmony and balance, gorgeousness, even glamour. She deplores the ugly (mostly male) expressions of squalor, outrage, abstraction, formlessness and misogyny endemic in modernist and contemporary art.

Steiner may be recognising a hitherto suppressed feminine aesthetic but even to dare to speak of beauty seriously is to lay herself open to accusations of naivety, self-deception and a lack of humour. And, also, of course, of gross political incorrectness. For was not the experience of Beauty largely reconstructed in the eighteenth century as an affirmation of bourgeois capitalist identity, as the Marxist critic Herbert Marcuse has proposed? Rich and powerful men desire to possess it as a sign of their wealth and power – their lovely architectures and landscaped vistas, their art and clothes, their beautiful women and children, indicative of their superior position, health and happiness. In the grumbling skirmishes between the feminists and the Marxists, is Steiner not complicit with this state of affairs? Worse, the evolutionary psychologists have reconstructed much the same thing and, as we shall see in Chapter 4, some theorists and social scientists believe they may even have a political agenda.

But while they may scorn such relativist discussions, scientists are not talking about the domestication of Beauty. For them real Beauty is altogether a more profound entity and is aligned with Truth, the truth of a unified Reality waiting to be revealed. Of course there is a paradox at the heart of this belief. Scientists are examining the material world of real things working in particular ways. But even if they start out simply making observations, whether of stars, fishes or brain cells, they cannot resist looking for patterns, which leads to the positing of empirically or logically provable hypotheses. If these start out on the level of ‘just supposing’, in the most rigorous practice the Popperian system is brought into play, attempting by replicable experiment to disprove them until there is sufficient evidence remaining which cannot be disproved, and which, therefore, may point to the right answer for the time being. Scientists know that while breakthroughs are hailed, paradigms shift. And yet, even if their task is to observe change itself, as in dynamic systems or as a consequence of entropy or environmental breakdown; moreover, even while many will claim to have no religious affiliations and to be robustly atheist or agnostic, the majority express a faith in the notion of an absolute knowledge which demands a high order of visionary thinking.

Scientists may be motivated simply by curiosity – how does it work, rather than why. Nevertheless, a quest for completeness recurs throughout the history of science and it is interesting to learn that this vision originally had more to do with mysticism than with clear reason operating in harmony with empirical investigation. It has ancient roots and connects with unified world-views which can be traced back as far as the emergence of the religious cosmologies of the early hunter-gatherers. The teachings of Pythagoras were bound up with a mystical belief that there existed a primordial substance present in everything, with man as a microcosm of the macroscopic universe and united to it by a divine, eternal spirit, a World-Soul. ‘It is perhaps fitting that Pythagoras was a near contemporary of Buddha, Confucius, Mahavira, Laozi and probably Zoroaster,’ the historian of mathematics Richard Mankiewicz points out.8 Followers of Pythagoras acknowledged that nature was in a perpetual state of flux, change or metamorphosis, but this in itself was manifest of a kind of eternal constancy. Mathematics was the one true source of knowledge, geometric proofs existed beyond the boundaries of human life and numbers were mystical entities which had both philosophical and revelatory roles. That there were numerical relations in music was only evidence that the earth was at the centre of a harmonious universe, around which orbited the music of the planetary spheres. The quest to explain nature in simple terms was a preoccupation of other pre-Socratic philosophers, some of them possessing intuitions which foresaw modern scientific theory. Anaxagoras believed that all heavenly bodies contained the same constituents as Earth and that nature was built from an infinite number of minute particles, which he called ‘seeds’, entities which Democritus went on to call ‘atoms’.9

The twin pillars that support western thought, and consequently science, derive from two of the greatest philosophers in the epistemological tradition. Both Plato and Aristotle were concerned with the nature of knowledge itself – the relationship between the wide external world ‘out there’ and our internal perceptions and experience of it. Plato was influenced by Pythagoras’ view that the existence of mathematical constants is a clear indication of the existence of a reality which is eternal and immutable, if only partly accessible to human perception. Plato’s ‘forms’ or ‘ideas’ exist as abstract entities, providing a universal template for every object in existence, and the material world presents to us mere imitations or shadows of the real thing.10 The route to this higher state is reason, a means of posing questions and answers to tease out inner truths, and it can also operate through the deductive logic implicit in mathematics. Euclidean geometry’s ideal forms are the circles, triangles and rectangles, the cones, cubes and pyramids used in hypothetical problem-solving and while some of these concepts relate to everyday measurements, they also exist in an imaginary space where ‘a point is that which has no part’ and ‘a line is a breadthless length’, where lines run parallel to infinity, and infinitesimals diminish as far as the imagination will stretch.11 Aristotle, however, disagreed with the notion of a Platonic ideal and believed the forms to be simply characteristics of concepts we had arrived at through actual experience. Although we might subscribe to the vision of underlying coherence in nature, we can only trust the evidence of our own perceptions in investigating it. Aristotle was the first biologist, examining plants and animals to discover their nature step by step, then going on to classify them by their basic functions.

Platonic reason and Aristotelian empiricism shadow and illuminate each other in ‘natural philosophy’ onwards and through to the Enlightenment. Even today, we can broadly see Platonic tendencies in the thinking that underpins mathematics and physics while Aristotle’s emphasis on the primacy of observational and empirical methodologies motivates the biological sciences. When the divine influence of a single Creator was brought into the picture in the post-Classical era, broadly speaking, Aristotelian principles went on to influence Islamic science, while Plato’s ideas were routed into early Christian and Judaic – Neoplatonist – ideologies, informing them with a pantheistic vision in which God and nature were as one. Descartes’ cogito ergo sum – ‘I think, therefore I am’ – gives priority to independent rational thought over empirical or sensual investigation. And, as a dualist, Descartes regarded mind and matter as separate manifestations of God’s will. Spinoza, on the other hand, rejected Descartes’ dualism and posited the existence of a single infinite reality or Substance of which God was the immanent cause. Eternity could be glimpsed through mathematical deduction which demonstrated that nature was ultimately governed by coherent universal laws.12 Newton was to discover the basis of such universal laws – the laws of motion, of gravitation and the science of mechanics – and went on to lead the way for examining phenomena such as the nature of light, colour, heat, acoustics and fluids.13 And in positing that the force acting on a falling body and the force acting on the planets in orbit were one and the same, Newton’s genius was to recognise that the same natural laws operate on earth and in the heavens.

The Enlightenment is generally regarded as the impetus for the origins of modern science in eighteenth-century Europe, uniting thinkers through a belief in the supremacy of reason, particularly in the face of superstition, religious intolerance and injustice. Aristotelian empiricism was a major influence on materialist thinkers such as Hobbes, Locke and Hume who denied the existence of innate ideas, claiming instead that all knowledge is derived from sense-experience. ‘Beauty is no quality in things themselves. It exists merely in the mind which contemplates them,’ wrote the Scottish philosopher David Hume.14 The Platonic vision of reality deduced through innate reason and Aristotelian empiricism in actually encountering it, were brought together in the epistemology of the founder of German Idealism, Immanuel Kant. Kant both agreed with and countered Hume’s scepticism by arguing that the human mind can neither confirm, deny nor scientifically demonstrate the ultimate nature of reality. He also recognised that through the very process of perceiving and acquiring knowledge, we partly invent the world by our means of measuring it – in space and time and by the ‘orders’ he categorised as quantity, quality, reason and modality. Reality and our encounters with it are therefore set in ceaseless interplay with each other.

Kant’s deliberate ambivalence seems to mark a dividing point for art and science. The consequence for science was that reality came to be regarded as something ‘out there’, to be explored as a thing in itself, and increasingly through physics rather than metaphysics. Even if the world had no ultimate purpose, its phenomena could be observed and classified to discover whether there was an inherent order in nature. The Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus, in his Systema Naturae of 1735, created a regularised method of the classification of plants according to their sexual characteristics, informed by a belief that there was an ultimately hierarchical system which encompassed the whole of life. Although Linnaeus recognised that natural history must predate the Bible’s chronology, Nature was the consequence of a God-given harmony. Linnaeus’ contemporary, the French naturalist the Compte de Buffon, however, took the view that all classification systems were artificially contrived devices. And in philosophy Hegel and his followers were to promote the notion that we invent the world we perceive, going on to deny the existence of a self-contained reality and eventually claiming that history, time and religion were all human constructs, ideas which were greatly to influence arts theorists in the twentieth century (see box, page 22).

By the nineteenth century, many influential intellectuals including, of course, Karl Marx, were openly expressing uncertainty about the existence of God.15 Among such doubters was Darwin himself, although even with a family history of vigorous liberal thinking, he held traditional Christian beliefs. His idea that all life, in...