![]()

CHAPTER 1

METHODOLOGY

The purpose of this book is to establish a typology for the horses of the ancient world. This typology will be used to examine how the form (conformation) of a horse dictated function – how the horse was used. To accomplish this I have used a multi-source approach to the topic by incorporating artistic representations, literary evidence, other material remains, native breeds and experimental archaeology. All of these sources have inherent advantages and disadvantages when used on their own, but when combined they provide a more complete picture of the horses of the ancient world.1

One of the main problems related to the study of ancient horses is terminology, especially in relation to horses and ponies, or breeds and types. A distinction between ‘horse’ and ‘pony’ did not exist in antiquity. Categorization by height is arbitrary. Standard practice today dictates that any equine 14.2 hands high (hh) and under is a pony, while anything over that height is a horse.2 This standardization does not always work: a 14 hh Arabian or Quarter Horse is still a horse, not a pony. Likewise, the Caspian horse of Iran rarely exceeds 13 hh, but is physiologically a horse. The pony is a distinct zoological type that traces its descent from the primitive pony of the Ice Age. Genuine ponies have an ample girth and very efficient digestive organs, which enable them to deal with a food supply that is both meager and difficult to digest. Their legs are strong but comparatively short, intended not for high speeds but rather for maintaining a consistent pace in difficult country. Ponies are sure footed, have plenty of stamina and are of robust health. Overall, ponies are considered to be tougher than horses and are often ‘good doers’. Based on its size to strength ratio, the diminutive Shetland pony is actually the strongest living equine. Many of the horses of antiquity, particularly from the Mediterranean, are miniature horses rather than ponies. These animals have longer, thinner legs, a lean build and generally a ‘dry’ appearance. Few of them, however, would have exceeded the 14.2 hh height criterion we now use to distinguish a horse from a pony. The large horses we are accustomed to today were the result of direct human intervention and they generally require much more care than the smaller horses of antiquity.3 In cases where these larger animals become feral, such as the ‘wild’ descendants of the Spanish horses in the New World, they revert in size and general appearance to resemble their ancient ancestors.4

The ancestral horses, those horses that existed before domestication, are called types. They are typically assigned to one of four categories: Equine Type 1 from Northern Europe, Equine Type 2 from the Northern Eurasian Steppe, Equine Type 3 from the Southern Steppe, Equine Type 4 from the Near East. In discussing domestic horses we generally try to assign every horse to a particular breed. But this method cannot work. When we employ the world ‘type’ we refer to ‘a horse that fulfills a particular purpose – like a cob, a hunter and a hack – but does not necessarily belong to a specific breed’. ‘Breed’, by contrast, denotes ‘an equine group bred selectively for consistent characteristics over a long period, whose pedigree is entered into a studbook’.5 To use the term ‘breed’ to classify the horses of antiquity is both anachronistic and artificial. Today there are well over 200 recognized breeds of horses and ponies, most with their own studbooks and registries. There are some very distinctive and unique breeds, usually throwbacks to ancient ancestors, such as the Norwegian Fjord or the Icelandic horse, but these are the minority. I have found that the majority of breeds can be placed into groups based on their physiognomy. One example of this is the European sport horse. This group includes the Hanoverian, Oldenburg, Dutch Warmblood, Danish Warmblood, Selle Francais, and Trakehner. Their origins lie in the warhorses of the Medieval world. In more recent times, infusions of Arabian and Thoroughbred blood have lightened their build, changing their conformation to a form suited to the show ring rather than the battlefield. Each of these breeds has its own studbook with very strict entry requirements based on size, colour, markings and – for stallions in particular – evaluation judging movement and paces in hand and while being ridden. In reality these sport horse breeds are all very similar to one another: they come from a particular geographical region and are bred to excel in the Olympic disciplines. Thus, it is not surprising that they would be conformationally alike. Similar trends can be seen with the draft type, mountain and moorland type, steppe type etc. This classification as ‘type’ instead of ‘breed’ should also be applied to the horses of the ancient world. Indeed, I believe it is even more appropriate at that time since horse breeding and physical appearance was determined more by environmental than human influences. In other words, there was very little specialized horse breeding in the ancient world.

ARTISTIC REPRESENTATIONS

The horse is ubiquitous in the art of the ancient world, appearing on temple pediments and friezes, victory monuments, tombs, in sculptural groups, equestrian statues, on vases and other ceramics, in frescoes and mosaics. In fact, one would be hard pressed to find a medium of ancient art from which the horse is absent. The horse turns up with such frequency that it is easy to ignore him. He becomes part of the background, or a stock figure in a scene. When we do notice them, horses in art are regularly dismissed as being either too ideal or too abstract to be of any use in determining the physical appearance of ancient horse types. In the case of the Parthenon frieze, the standard comment is that the horses have been portrayed smaller than they actually were to exaggerate the human form. Such commonly held misconceptions cause scholars to disregard the value of equine imagery. In fact, these painted and sculpted horses can provide a wealth of information. They are remarkably consistent in their depiction of certain conformational features. To explain this, one may consider the following two examples of Greek horses.

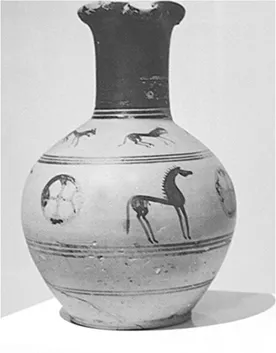

The first example from the eighth century BCE presents what we might call an abstract representation of the horse (Fig. 1.1). There are, however, specific conformational features that the artist has chosen to emphasize. These include

FIGURE 1.1 Trefoil oinochoe attributed to the Painter of the Roaring Lions with a late geometric representation of a horse, c.740 BCE.

- Very upright head carriage that arches at the poll

- A slender face with a straight profile

- A lean body

- Muscular hindquarters

- Long legs

Particular emphasis is given to the neck and hindquarters, juxtaposed with the slenderness of the body and legs.

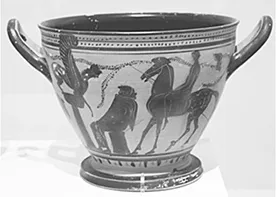

The second example, from the late sixth/early fifth century BCE is a great deal more ‘fleshed out’ and very clearly equine (Fig. 1.2). Despite the considerable attention to detail, the conformational features emphasized are identical to those of our more abstract horse with an upright, muscular neck; narrow, straight face; lean body; muscular haunches; long, slender legs – elements that we can call hallmark characteristics of the Greek horse.

The above two examples show that even an ‘abstract’ representation of a horse displays aspects of reality. The Greek images of equines all display the same conformational features. The importance of these features and the overall appearance of the Greek-type horse are discussed in relation to the Mediterranean horse.

FIGURE 1.2 Black-figure Skyphos attributed to the Painter of Philadelphia, c.500 BCE.

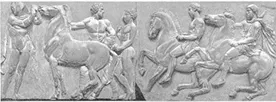

At the opposite end of the scale from our abstract, linear horses are those labelled as too ideal to be real. The prancing, galloping horses of the Parthenon frieze are a prime example of this style of iconography (Fig. 1.3). These poor horses seem to receive constant scholarly abuse: either they have been down-sized/shrunken to exaggerate the human form or they are too perfect to be representations of real animals. The first argument (that of the dwarfed horses) will be addressed throughout the book; the second statement (the perfect horse) can be dealt with here. The claim that the Parthenon horses are ‘perfect’ or ‘ideal’ is indeed correct. The equines sculpted on this frieze are the ideal equine. This does not, however, discount their usefulness to this study. What we see on the Parthenon frieze is the ideal specimen of the Greek horse. Pheidias and his colleagues portrayed the horses they were familiar with – native Greek stock – but as perfect specimens. Of course, the perfect horse does not exist today, nor did he in antiquity, but the concept of perfection did. This ideal equine is described by Greek and Latin authors – Xenophon, Virgil, Varro, Columella, Vegetius, Oppian – and he appears regularly in art. He is the ancient equivalent of our modern breed registries and studbooks. These registries contain descriptions of the ideal specimen for that particular breed or type. Any horse intended to be included in the registry is evaluated against this standard of perfection on conformation, movement and temperament. The idealized representations from antiquity are like these studbooks. They depict the native horses the artists saw on a regular basis as conformational ideals. The physical features found on these representations are the same as those on the living horses; the only exception being that the living examples would not have possessed every conformational ideal.

FIGURE 1.3 Sketch detail from the west frieze of the Parthenon.

We also must answer this question: whose horses are being portrayed in the art? This is especially relevant if we look outside Greece proper at the Greek colonies of Asia Minor and the Black Sea, as well as Rome, particularly in the late Republic and early Imperial periods. In areas of rich cultural interaction, such as Greek colonies where Greek artists might be producing commissioned pieces for ‘natives’, it does seem fair to ask ‘which horses are these?’ Likewise in Rome, where artistic styles from all over the Mediterranean and its history were imported and re-invented to suit Roman tastes and ideas, we might question the veracity of the equids produced. Are these Roman horses or not? Once again I am confident in stating that the animals portrayed are the native equines, local horses familiar to both artist and commissioner were familiar. It is hard to imagine a Scythian chieftain would commission a piece and allow a horse other than his own type to be portrayed.

Similarly Roman art, for all that it borrows and adjusts styles of other cultures and earlier periods, nonetheless portrays an Italian horse. The Alexander Mosaic from the House of the Faun in Pompeii is an excellent example of this. Herodotus tells us that Nesaean horses always pulled the chariot of the Persian king:

After them came the ten sacred horses called Nesaean, splendidly arrayed. (They are called Nesaean after the great plain in Media that produces these big horses.) Behind these ten horses came the sacred chariot of Zeus, drawn by eight white horses, and in behind the horses their charioteer followed on foot, holding the reins; for no human being may mount into the seat. Behind this came Xerxes himself in a chariot drawn by Nesaean horses.6

The Nesaean horse has a very distinct appearance, with his convex rams head, thick powerful neck and stocky body. The four black horses yoked to Darius' chariot in the mosaic, however, are distinctly not Nesaean. Much like the Macedonian horses, they fit the standard Italian/Greek type.

LITERARY EVIDENCE

The literary record is full of references to horses. No matter what the genre, the horse always makes an appearance. Inscriptions, particularly the circus inscriptions from the Roman Empire, are one important source of written information. Successful charioteers were fond of putting up monuments listing the names, colours and ‘breeds’ of their best horses. Likewise, lead tablets from the Athenian Agora record the colours and brands of cavalry mounts brought in for the dokimasia.

As far as extant Greek and Latin texts are concerned, Xenophon's Art of Horsemanship is by far the most detailed horse-training manual surviving from antiquity. This text deals with selecting a conformationally sound animal, training, care, exercise and equipment. Most of the advice offered by Xenophon is sound and continues to influence horsemanship and training today. The Art of Horsemanship was the impetus for the revival of ‘Classical Riding’ in fifteenth-century Europe. Through the Renaissance texts the ideas of Xenophon have been passed down to the modern discipline of Classical Riding through the traditions of the Spanish Riding School in Vienna, the Cadre Noir at Saumur in France and the Royal Andalusian School of Equestrian Art in Jerez, Spain. Xenophon produced a second text devoted to horsemanship. His On the Cavalry Commander discusses the duties and obligations of the cavalry commander, as well as training exercises for war and spectacle.

The other major horse-related texts deal primarily with horse husbandry. The practice of hippotrophia is treated by Varro and Columella (On Agriculture), and Vegetius (On Veterinary Medicine) all of whom present detailed accounts of horse breeding, raising and care. Virgil (Georgics) likewise devotes some time to the ideal horse and how to train him. Aristotle (On the Generation of Animals) examines the reproductive cycles of the horse. Oppian (On Hunting) gives the most substantial list of horse ‘breeds’; but references are found in other authors, most notably Strabo (Geography) and Pliny the Elder (Natural History).

The military horse appears in both historical prose and ‘historical’ poetry. There is also a tradition of equine anecdotes, most notably in Aelian's Historical Miscellany and On Animals. Whatever context the horse is mentioned in, even if it is only an allegorical horse, it is clear the author was familiar with horses. For example, Arrian writes thus of horses and elephants:

It was clear to him [Alexander] that he could not effect the crossing at the point where Porus held the opposite bank, for his troops would certainly be attacked, as they tried to gain the shore, by a powerful and efficient army, well-equipped and supported by a large number of elephants; moreover, he thought it likely that his horses, in face of an immediate attack by elephants, would be too much scared by the appearance of these beasts and their unfamiliar trumpetings to be induced to land – indeed, they would probably refuse to stay on the floats, and at the mere sight of the elephants in the distance would go mad with terror and plunge into the water long before they reached the further side.7

Likewise, Euripides' description of Hippolytus' runaway chariot rings true for anyone who has ever experienced first hand a bolting horse:

And sudden panic

fell on the horses in the car. But the master –

he was used to horses' ways – all his life long

he had been with horses – took a firm grip of the reins

and thrashed the ends behind his back and pulled

like a sailor at the oar. The horses bolted:

their teeth were clenched upon the fire-forged bit.

They heeded neither the driver's hand nor harness

nor the jointed car. As often as he would turn them

with guiding hand to t...