- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Morocco has long been a mythic land, firmly rooted in the European colonial imagination. For more than a century it has been appropriated by travellers, explorers, writers and artists. It is just these images and imaginings that are now being reconstructed for nostalgic consumption. In Moroccan Dreams, Claudio Minca examines this aestheticised re-enactment of the colonial, exploring the ways in which Moroccans themselves have become complicit in the re-writing of their homes and lives. Richly illustrated, the book provides a fascinating journey that will engage and delight all those enamoured of Morocco and its extraordinary geographies.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

YES, WE CONSERVE

Yes, in Morocco, and it is to our honour, we conserve. I would go a step further, we rescue. We wish to conserve in Morocco Beauty – and it is not a negligible thing. Beauty – as well as everything which is respectable and solid in the institutions of the country … all of your researchers conserve and save, whether it be a question of antiquities, fine arts, folklore, history, or linguistics. We found here the vestiges of an admirable civilization, of a great past. You are restoring its foundations.

(Lyautey, at the Congress of the Hautes Études Marocaines, Rabat 26 May 1921; in Lyautey 1995 [1927]: 384; translated in Abu-Lughod 1981: 142)

Paroles d'action

Through his Paroles d'action (1995 [1927]) – the title of the collected speeches that exemplify his attitude towards leadership – Résident-Général Maréchal Hubert Lyautey (see Figure 1.1) has left an impressive legacy on Moroccan urban landscapes and on the ways in which contemporary Moroccan historical patrimony is conceived. Lyautey's urban ideology, his mark on Moroccan cities, on definitions of the ‘essence’ of Morocco and its culture are still present and implicitly (sometimes even explicitly) celebrated today. Le Maroc as imagined by this one man still provides the stage and often the material support for most representations of the country travelling abroad, in Europe in particular; representations that, as far as cultural tourism is concerned, are also circulating for domestic consumption. This is possibly one of the few cases in history where a former colonizer is so often presented as an educated modernizer, who recognized and valorized the unique culture of the colonized land and people. The contemporary rhetoric used to ‘sell’ a romanticized and exoticized image of Morocco is populated by slogans and ‘orange’ images that resonate with Lyautey's colonial fantasies and with the actual translation of Morocco into a European space of a certain kind. The cultural geographies of late postcolonial Morocco are in fact still negotiated in relation to the legacy of the Protectorate, a legacy and influence that go well beyond the achievements of the 13 years of his distinct personal regime (see, among others, Hoisington 1995; Le Révérend 1983; Maurois 1931; Pennell 2000; Rivet 1988; Scham 1970; Usborne 1936; Venier 1997).

One claim of this book is that it is literally impossible to understand the ways in which modern Europe invented a place called le Maroc, and the ways in which contemporary European travellers are still imagining and travelling to that very place, without a full engagement with this legacy. The discursive formation defining the past and present appel du Maroc (see Rondeau 1999) is thus a crucial site for the exploration of how Europeans' real and imagined experience of Morocco is presented today by Moroccan authorities – and interpreted by many Moroccans in their dealings with tourists. This book is an account of some of the spatial orderings linked to the enactments of the returned colonial gaze produced by these encounters. From the dual city model, which still underlies the overall structure of many Moroccan cities and their official cultural geographies, to the ways in which culture and art are publicly defined, Lyautey's ghost seems to be everywhere, but is especially visible in those spaces directly or indirectly involved with Europe and Europeans. These spaces and their itineraries through Morocco, still rife with the most orientalist elements of his ideology (see, for example, Minca and Borghi 2009), are at the core of our investigation.

Figure 1.1 Lyautey (Agence de Presse Meurisse 1920)

The French rule in Morocco, embodied by Lyautey's persona and ideology, was, among many other things, also an attempt to realize a laboratory for social modernity. The establishment of the Protectorate in 1912 did not, indeed, merely mark the formal incorporation of Morocco into the French colonial empire after a long pursuit: it was also the beginning of a grandiose experiment in social engineering. It is in Morocco that the late nineteenth-century techniques and socio-cultural categories elaborated in the métropole would first be put into practice, in the attempt to realize, in these territories, the project of social pacification that was finding so many obstacles in France and outre mer (Minca 2006a). France somehow exported its social and ideological crisis to a re-invented North African country; not the first experiment of this kind to be sure. As famously illustrated by Paul Rabinow in his French Modern (1989), the French, and Lyautey in particular, saw in Morocco a great opportunity to rethink their take on modernity. Their colonial lenses convinced them that ‘there’ – in that messy and backward but still authentic and radically different outer space – they would be able to find the answers to the crisis of their own modernity, deprived of the corruption and the untenable compromises of the French political system. Some of the key protagonists of this experiment, who accompanied Lyautey in many of his projects, were indeed hoping to test in the Protectorate their social conservative idea(l)s that could not be implemented so easily in France.

The ‘discovery’ of Morocco, while reflecting in many ways the tenets of the most classic examples of orientalist discursive formations experienced elsewhere, was, however, rendered unique by the cultural geographies that were at the basis of Lyautey's colonial fantasies: that is, the spatialities of a putatively soft and gentle power, fascinated by and supportive of local history and tradition, while helping Morocco to occupy its place in the world via the celebration of its aesthetics and patrimoine. This is the way in which France attempted to (re)present its paroles d'action in relation to the revolutionary spatializations of the principle of association guiding Lyautey, a principle to which we will return in the pages to follow but that will also emerge in many of our chapters. Here, to begin, we follow Lyautey's pathway through imagining le Maroc – the colonized vision of Morocco that he both succeeded and failed in creating – as a cultural and spatial rendering whose traces are evident in the Morocco we find today.

Le Maroc

Le Maroc today – what can perhaps be defined as late postcolonial Morocco – and some of its dominant elites are still to some extent capitalizing on those very ideas in order to build a euro-centric, but simultaneously uniquely self-exoticized and North African, image for the country, tailored for the leisure consumption of European markets (see Borghi 2008a, 2008b). Many exemplifications of this will be discussed in the chapters to follow. Indeed, the present mapping and valorization of its tourist attractions rely largely on what Lyautey identified as le patrimoine marocain, something that he committed himself to discover, evaluate, classify and conserve:

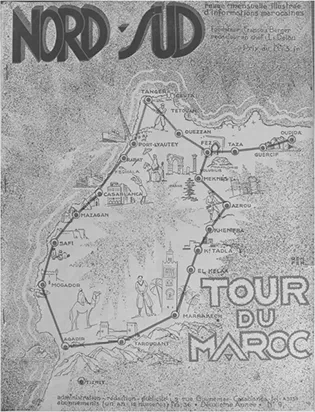

Figure 1.2 Cover of the Protectorate monthly Nord-Sud (c.1939)

Thanks to the permanence of assured power in all the successive continuous dynasties, thanks to the maintenance … of essential institutions, we have found a built Empire, and with it a great civilization. That was a real revelation.… the beautiful monuments of Morocco … still living beauties. We have a striking example of this in the arts: they were, so they say, lost, or being lost. It was only necessary to bring order so that these artisans and masters could be reinvigorated. It was not necessary to bring Moroccan arts back to life, only to prevent them from dying. And, at the same time, in the intellectual domain, as much as order was re-established, and as much as we penetrated further into intimate Moroccan society, we discovered scholars, savants, workers, and eminent men who were living just beyond the gap. (Lyautey at the Congress of the Hautes Études Marocaines, Rabat 26 May 1921; in Lyautey 1995 [1927]: 423–4)

Some of these ideas (and decrees) on heritage conservation and on ‘Moroccan traditional culture’, as we will show in the later chapters, are still in use and largely promoted by the tourist authorities. These mappings are also popular among the advocates of a ‘Moroccan difference’, that is, European and Moroccan public intellectuals, politicians or media stars claiming the supposedly unique position occupied by the country in bridging the Arab world to Europe and supporting an image of Morocco, together with the production of related spaces, that reveals clear continuities with the legacy of the extraordinary 13 years during which le Maréchal managed to entirely transform the country (see, for example, Goytisolo 1997).

European tourism to Morocco and some of its most celebrated and visited places can thus be seen as useful sites at which to reflect and actually encounter the effects of the returned gaze that makes le Maroc today; a gaze of which Lyautey may be considered, if not the initiator, certainly the main promoter. The gaze produced and legitimized in those years, we argue, is still embedded in the materialites found in some key tourist sites and in the colonial nostalgia pervading the contemporary reconnaissance du Maroc on the part of many Europeans. Their canonical ‘excursions’ to Morocco are indeed an intriguing arrangement of metaphorical and ‘real’ sites where Moroccans watching Europeans and Europeans eager to watch le Maroc et les Marocains meet in somewhat complicated ways.

Figure 1.3 Lyautey in action, in a French children’s textbook (Flandre et al. 1955)

These sites of encounter, their hard and soft spatialities, their related practices, are at the core of our own analysis. What we claim is that by exploring the workings of these mutual gazes in situ, we can learn a great deal about the European invention of Morocco and its tenets. While the European invention of Morocco traces back its origins to the earlier explorations of adventurous travellers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (see Chapter 2), Lyautey took what until that moment was simply one out of many European orientalist mappings of the Oriental Other and transformed it into a powerful and extraordinarily ambitious modern project. What Lyautey actually did was an attempt at an imaginative and audacious experiment in matching and merging his readings of Morocco's exoticism and unique cultural tradition with a modern social and political experiment of pacification and colonial association. Space and spatial theory were central to this attempt. This is why urban planners and, to some extent, geographers were so important for him and his plans (see Lyautey's letter to geographer M. Hardy, Directeur Général de l'Instruction Publique au Maroc, Lyautey 1995 [1927]: 383). This is also why we claim that a geographical investigation of these very real and imagined spatial orderings is necessary. The spatial implementation of his ideas was indeed thought to be the best way to resolve and dissolve these latter internal tensions and contradictions.

To realize that, it was necessary to forge a new land, a new French Morocco, of Europe, but also out of Europe: an imaginative cultural and functional spatial laboratory where things and people would occupy their proper place and where meaning would be translated into a manageable and, to some extent, aestheticized order:

The new generation brings an interest and a touching willingness to this study and works hand in hand with us to make a real link. This generation has the admirable advantage of possessing a taste for research, and is interested in the most modern questions, to be highly anxious about the traditions of this country, and fond of its history and grandeur. One can make a good and beautiful Morocco by remaining Moroccan and Muslim. (Lyautey at the Congress of the Hautes Études Marocaines, Rabat 7 December 1922; in Lyautey 1995 [1927]: 424–5)

We knew, in Morocco, that to govern with a spirit and a reciprocal tolerance for which I give you all my congratulations … Here it has been thirteen years that we work together, under this locked and practical form, and we can be proud of what we have done to Morocco.… I am full of confidence in the future of such a vibrant and well-ordered organism that is Morocco. (Lyautey, Paroles d'adieu au Conseil du Government, Rabat 5 October 1925; in Lyautey 1995 [1927]: 480–1)

In this endeavour, Lyautey was strongly influenced by a group of French intellectuals gathered in those years around the Musée Social (see Rabinow 1989). Drawing on their theorizations, le Maréchal believed that in the colonial context an inverse ratio existed between the welfare of a society and its dependency on overt forces of order. Order achieved by force was, indeed, less desirable and more costly than a ‘well-tempered social regulation’: a vision that the Résident-Général would promote in many of his speeches. Combining their influence with his military and colonial expertise, this project was centred on three key concepts: the ideal of the ‘association’, the ‘dual city’ system, and the related valorization and respect of the political system and cultural traditions of the country entutelage. The legitimacy of the Protectorate was based within the application of these very three concepts. The concomitant ideal of ‘pacification’ had strongly marked his previous colonial experiences in Indochina and Madagascar, bound to an attempt to identify the ‘scientific’ and cultural bases of a ‘durable and harmonious social order’. In Lyautey's vision, colonized peoples were to be incorporated not by force but, rather, by assuring their full adhesion to the civilizing mission of ‘la plus grande France’:

Finally, you have wanted, from the beginning, to make a place for indigenous collaborators… Do not forget, we are in the land of Ibn Khaldoun, who arrived in Fez at the age of twenty; the land of Averroes; and their descendants are not a disgrace to them… [We do not yet know enough of] the old residences, of Fez, Rabat and Marrakech, that housed men who made their home in reading, thinking and research.… [They remain a little withdrawn, but they are easy to tame once we show them intellectual sympathy]; as soon as they know we appreciate their value.… We should each adapt to the other. And there is no place more favourable for this communion that this Institute, where, at least, in emulation, in free research of Beauty and Truth, our interests will never collide… It is a place of social peace, a welcoming home of which close and cordial association forms the most solid and magnificent basis for a future that we ever dreamed of for this rejuvenated Morocco. (Lyautey at the Congress of the Hautes Études Marocaines, Rabat 26 May 1921; in Lyautey 1995 [1927]: 386–7)

Albert Sarraut, a prominent advocate of the association principle and former Minister of the Colonies, summarized the relation of the colonies to France as that of pupils to their teacher:

Instead of adapting all our protégés by force to the conditions of the Metropole, according to the old assimilationist error, it must be understood that, under our tutelage, their evolution should be pursued in keeping with their civilization, their traditions, their milieu, their social life, their secular institutions. (Sarraut 1923: 104; translated in Morton 2000: 188)

It was in these very years, too, that the principle of ‘assimilation’ that had guided French colonial politics thus far was being seriously questioned. Problematic, above all, was its inherent contradiction: France justified its presumed superiority over colonized cultures by appealing to ‘universal’ values that guided its mission civilisatrice – a set of democratic and egalitarian values that were to bring progress and justice to the peoples under its rule. Yet once colonial subjects achieved these ideals, France's mission would have exhausted its declared aims, thus depriving the colonial project of its legitimizing rhetoric. New justifications for French colonial rule would therefore have to be formulated. As Patricia Morton has noted, in the ‘late colonial order’, the claim to authority made by the colonizers was dependent on,

the relative superiority of metropolitan culture rather that the innate right of Europeans to colonize other peoples. The change in French policy from assimilation (the prerogative of colonizers to colonize based on their absolute superiority) to association (predicated on the contingent, if definitive, superiority of colonizers) clearly delineated this shift from innate right to relative order. Preservation of this order of things was based on visual classification of the colonial landscape, etiquette, body language, architecture, clothing, and other outward signs of authority. (2000: 204)

In response to the new theories of race and evolution elaborated in those years and conditioned by the negative results of assimilationist policy in the colonies, the French elites embraced the new ‘native’ policy of association. This policy was to be grounded in a strict physical, political and cultural segregation of natives from the French population: the ideal of the association was predicated, indeed, on the precise and subtle differentiation and division of peoples, societies and cultures into race-based hierarchies. As Morton argues,

the colonized peoples had to be proved barbarous to justify their colonization, but the mission civilisatrice required that they be raised above this savagery. If the colonized peoples acquired too much civilization and became truly assimilated to France, colonization could no longer be defended, having fulfilled its mission. (2000: 7)

They would also cease to be exotic objects of interest – a theme to which we will return subsequently.

The principles of the French colonial doctrine of association were to be most fully enacted by the Moroccan Protectorate, under Lyautey's vigilant guidance. Le Maréchal believed that by preserving local ways of life, association could sponsor the renewal of indigenous culture and the creation of a modern, prosperous colonial state. His so-called politique indigène left existing Moroccan cities intact and built new European cities alongside; retained the traditional Moroccan government, although under indirect French control; and encouraged indigenous arts and crafts through schools and workshops set up by the French. According to Harmand (1910) – one of the key theorists of the association principle – colonial policies were to allow ‘indigenous peoples’ to evolve in autonomous fashion, by ‘keeping everyone in his proper place’, appropriate to his role in society. ‘Native’ traditions and habits were thus to be influe...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1. Yes, we conserve

- 2. Mosaïque

- 3. Lyautey’s Dream

- 4. Medina

- 5. La Place

- 6. Kasbah

- 7. Sahara

- 8. Mogador

- 9. Lighthouse

- Finale

- Notes

- Bibliography

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Moroccan Dreams by Claudio Minca,Lauren Wagner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politica e relazioni internazionali & Geografia storica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.