![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE 50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE BEGINNING OF MIGRATION FROM TURKEY TO SWEDEN: LESSONS CONCERNING INTEGRATION, COHESION, AND INCLUSION

Paul T. Levin and Bahar Başer

The idea behind this edited volume is to evaluate trajectories of migration from Turkey to Sweden on the 50th anniversary of the start of this migration. Although the official agreements for labour migration between Turkey and Sweden were signed in 1967 (and though travel between Asia Minor and Scandinavia dates back to the time of the Vikings and Byzantines), Turkish diaspora organisations in Sweden as well as other relevant actors have taken 1965 as the year that migration to Sweden from Turkey started in earnest and organised a range of festivities during the year of 2015 accordingly. Hence, 2015 became an occasion for both state officials and migrants themselves to celebrate and discuss the experiences of Turkish migrants in Sweden and reflect upon the future. Turkish state institutions organised seminars on the topic and participated in celebrations arranged in Sweden. The Turkish national TV channel, TRT's religious Diyanet channel, produced and aired ‘Stockholm Train’, a documentary that included interviews with Turkish migrants and their experiences in Sweden. A number of migrant associations in Sweden created a joint committee to coordinate the celebrations and set up a website dedicated to the 50th anniversary, filled with stories and advertisements for events. There have also been festivities in the small Central Anatolian town of Kulu, near Konya, from where most of the ethnic Turkish migrants in Sweden originate. Similar celebrations have also been organised in Germany and the Netherlands, European countries where a large number of Turkish and Kurdish migrants reside.

Marking this date, the aim of this volume is to provide an overview of Turkish migrants' experiences in Sweden over the last 50 years, to present their stories and perspectives, and to identify challenges and opportunities with respect to the question of integration. In so doing, we also hope that this volume will make a broader contribution to our understanding of the integration of immigrants in northern and western Europe, a topic that is both politically charged and of great significance to contemporary European societies. In Sweden, as elsewhere in Europe, this topic is subject to lively discussion and debate at the time of writing, fuelled both by a rise in support for anti-immigration parties and by outrage over the tragic fate of refugees from the war in Syria. In this book, we build on the public conversation as well as existing research regarding the experience of Turkish immigrants in Sweden, while introducing a fresh scholarly contribution to the current debates on migration to Sweden, emigration from Turkey as well as the situation of migrants in Europe in general. Looking back at the achievements of migrants and Swedish institutions over the course of the past 50 years also gives us an excellent opportunity to evaluate Swedish policies concerning immigration and integration, which may reveal insights that can guide us towards policy lessons for the future.

The History of Migration from Turkey to Sweden

Immigration from Turkey to Sweden began in the mid-1960s with the recruitment of workers to satisfy the needs of the expanding Swedish industrial economy. At that time, the preferred destinations for Turkish migrants for labour migration were countries such as Germany, France and the Netherlands, which had signed labour agreements with the Turkish state. However, many also found their way to Sweden through individual networks. Most of these labour migrants from Kulu were characteristically of peasant origin, with a low educational background. The second biggest group was from Cihanbeyli, a neighbouring town to Kulu. There were also other migrants from different parts of Turkey, including Istanbul, who were high-skilled compared to those from Central Anatolia. These workers were not considered ‘guest workers’ as in the case of Germany, therefore the usual guest scheme did not apply to them in Sweden.1 Along with significant numbers of labour migrants from Finland and Southern European countries like Greece and Italy, Turkish migration continued until 1973, when Swedish labour unions, during the economic downturn that followed the oil crisis, introduced stringent restrictions on labour migration.

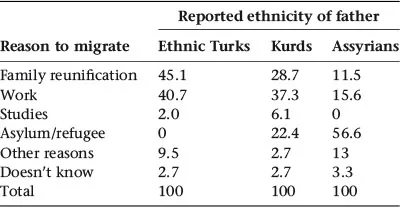

The profile of migrants from Turkey shifted with the arrival of asylum-seekers (mostly Assyrians and Kurds) who came to Sweden after the 1971 military intervention. In the 1970s and afterwards, family reunification also became a way to migrate to Sweden. Yet another wave of migration began after the military coup in 1980 and on this occasion the asylum-seekers were mostly, albeit not exclusively, of Kurdish origin. A sense of the diversity of this group and of the reasons for leaving Turkey can be gleaned from Table 1.1, which is adapted from a large recent study, The Integration of the European Second Generation (TIES), which will be discussed further below as well as in later chapters.

Table 1.1 Second generation Turks in Sweden, fathers' reason to migrate (per cent)3

Today, migrants from Turkey no longer constitute one of the larger migrant groups in Sweden. According to Statistics Sweden, there were 46,373 Swedish residents in December 2015 who were born in Turkey.2 However, if we include the children and grandchildren of the first generation immigrants from Turkey, we can safely say that the number of Swedes with their origins in Turkey far exceeds 100,000. Pinning down the exact number of ‘Swedish Turks’ is challenging because of naturalisation rates and uncertainty about how to count the second and third generations.

An Understudied Topic

Turkish migration to Europe has been a popular topic for researchers from various fields for decades. However, attention has usually been focused on the large number of Turkish migrants who reside in Germany, whereas other countries were understudied in the literature. Until very recently, our scholarly understanding of the migrants from Turkey in Sweden was based on a smaller number of empirical studies conducted by pioneering authors such as Alpay4, Lundberg and Svanberg,5 Lundberg,6 Erder,7 Akpinar,8 Jorgensen9 and Westin.10 Most of the authors were based in Sweden or Turkey, and their studies – often published in the format of PhD or MA Theses – were typically only available in Swedish or Turkish. In the English-language literature, Sweden was long overlooked as a host country. Only more recently have we begun to see studies on the Turkish or Kurdish communities in Sweden published in English. Several of the contributing authors to the current volume have published such theses and reports: Naldemirci,11 Akın,12 and Larrucea,13 while co-editor Başer is the author of a recent monograph on the Turkish and Kurdish diasporas in Sweden and Germany.14 Most of these publications are based on predominantly qualitative research that provides valuable insight into the Turkish community in Sweden but lack statistical data and the generalisability of their results consequently varies.

There are now also exceptions to the above-mentioned dearth of quantitative studies. Vedder and Virta15 modelled the psychological adaptation of Turkish migrants in Sweden and the Netherlands, looking at whether stronger competence in one's ethnic language or the host country majority language best predicts adaptation. Bayram et al.16 measured the integration of Turkish immigrants in Sweden, looking at their perceptions of ethnic identity, media consumption habits, and transnational ties to Turkey. Both of these studies found that Turks in Sweden maintain a comparatively strong Turkish ethnic identity and ethnic language competence. Interestingly, Vedder and Virta found that this also appeared to be a recipe for psychological adaptation, whereas stronger competence in Swedish did not predict adaptation. Two larger recent international quantitative studies have also featured Turkish-origin immigrants in Sweden: ICSEY (International Comparative Studies of Ethnocultural Youth) and the above-mentioned TIES. The latter project is a broad comparative study based on surveys conducted in several large European cities, and it has generated a smaller number of important publications on the Swedish case. The most notable of these is the Swedish TIES volume edited by Charles Westin17 and published in 2015, on the 50th anniversary of the beginning of Turkish migration to Sweden. The TIES study generated similar results to Bayram et al. and Vedder and Virta when it comes to the comparatively strong self-identification of their respondents as Turks, but adds several layers of complexity to our understanding of identity and sense of belonging. In fact, the TIES project and Westin's anthology, which are wholly quantitative, raised a number of questions regarding integration, identification and institutions that demand further study, and several of the chapters in the current volume therefore take the TIES study as their starting point.

A significant drawback of many of these quantitative studies is that they focused on ‘Turkish migrants’, including Kurdish and Assyrian groups without fully acknowledging the heterogeneity of this community or paying attention to the often very different experiences of these groups, which emigrated from Turkey for very different reasons and arrived in Sweden under varied conditions. (As Westin argues in Chapter 2, this critique also applies to the TIES study, even though it did include questions about respondents' Turkish, Kurdish, or Syriac ethnic identities.) Our general conclusion from reading the existing literature was therefore that there are gaps to be filled and that this topic deserved further attention. For that reason, we gathered a group of scholars at a workshop at the Stockholm University Institute for Turkish Studies on 9 October 2015, and the current edited volume is the outcome of that process.

What is so Special about Turks in Sweden?

As we have just argued, compared to the burgeoning academic literature on other Turkey-originated migrant communities in various European countries, the overall number of studies focusing on Sweden is still relatively low, especially if we limit ourselves to English-language publications. This is surprising in light of the fact that Sweden harbours a highly interesting amalgam of ethnic and religious groups from Turkey that is unique in a number of ways. For one thing, almost 40 per cent (and a majority of the ethnic Turks)18 of them originate from a single small town: the above-mentioned district of Kulu in Konya, central Anatolia. Rarely in Europe do we find this high degree of concentration of Turkish immigrants in terms of their place of origin.19 This pattern of labour migration matters: the social and political attitudes, sense-of-belonging and diasporic activism of the ‘Kulu-Turks’ in Sweden have arguably been very much affected by a shared and nostalgic idea of the small town as well as by their traditional and often conservative background. The ‘Kulu connection’ as they call it, also became an important focal point for relations between the Swedish state and the Turkish migrant community. There is a park in Kulu named after the late Swedish Prime Minister, Olof Palme, and Sweden recently opened an honorary consulate there where returnees to Kulu can vote in Swedish elections. Hence, the case of migration from Turkey to Sweden promises to give us special insight into popular issues today such as return migration, transnational ties or external voting and citizenship rights.

Paradoxically, the composition of immigrants of Turkish origin in Sweden is also distinctive in terms of the breadth of geographic origins compared to the diaspora in other European countries. Hence, apart from the large number from the central Anatolian town of Kulu, TIES data shows that the immigrants from Turkey in Sweden trace their origins from places as diverse as Mardin and Diyarbakır in the south-east, the northwestern cities of Istanbul, Sakarya, and Bolu, as well as other Anatolian cities like Ankara and Nevşehir. The ethnic composition is also unusually diverse, with large numbers of self-identified ethnic Turks, Assyrians/Syriacs, and Kurds, respectively. Among the latter, an unusually high proportion speaks the small and distinctive Kurdish dialect/language of Zaza. In terms of religion, Assyrians are almost exclusively Christian, but among Kurds and Turks we also find an uncharacteristically high proportion of Alevis alongside the Sunni Muslim majority (and of course also many who are secular or atheists).

Sweden is also a special case when it comes to the Kurdish diaspora. As was suggested in Table 1.1 regarding the reason for emigration, the Kurds are divided between labour migrants (mainly from Kulu), and political refugees (from Diyarbakır, Ankara, and Istanbul, many of them having had to flee around the time of the coup in 1980). It is a simplification but one not without merit to say that the latter group of refugees tended to be leftist in political orientation and many of them continued their political activism in Sweden, whereas a large proportion of the Kurds coming from Kulu tend to be more conservative Muslims. The politically mobilised parts of the Kurdish diaspora, thanks to the opportunities provided by the Swedish state, managed to revitalise the Kurdish language (in particular the main dialect spoken in Turkey: Kurmanji) at a time when it was forbidden in Turkey, and more generally contribute to the preservation of Kurdish culture. In Kurdish studies, the diaspora activism of the Kurds in Sweden is recognised as so significant that it has been given its own name: ‘Isvec Ekolu’ (the Swedish School), a distinctive approach that placed great importance on keeping language and culture alive.

For its part, the Assyrian/Syriac community in Sweden has a symbolic importance to the rest of this diaspora outside of Sweden. Due to forced deportations or ‘voluntary exile’, many Assyrians left Turkey and chose Sweden as their new home. It is said that there are currently more Assyrians living in Sweden than there are in Turkey. They are active in Swedish political circles, and elements in both the Kurdish and Assyrian groups have been highly successful when it comes to integration into the Swedish public sphere, with a number of high-profile athletes, artists, columnists and politicians.

In light of the fact that the case of Sweden as a host country clearly provides researchers with an abundance of topics that should be of interest to audiences beyond Sweden, the relative dearth of English-language publications is surprising. Moreover, apart from being interesting i...