![]()

~1~

STRATEGIC PRIZE

Britain’s Vital Military Base

In a top secret briefing note in 1950, British military chiefs of staff spelled out the importance of Cyprus to Britain. They warned defence ministers that if Britain wanted to keep its position in the Middle East, Cyprus must remain British; moreover, even in peacetime the popular communist movement on the island must never be allowed to win control. It was, they said, the only way to ensure the future of Britain’s military facilities there, and any weakening of this commitment would alarm Britain’s key allies, since Cyprus was a vital link in the chain of British bases running through the Mediterranean to the Middle East and beyond. ‘The effect on Turkey and other Middle East countries, and indeed the United States, of any abrogation of British sovereignty is likely to be so serious that it is strategically necessary for Cyprus to remain British,’ they said.1

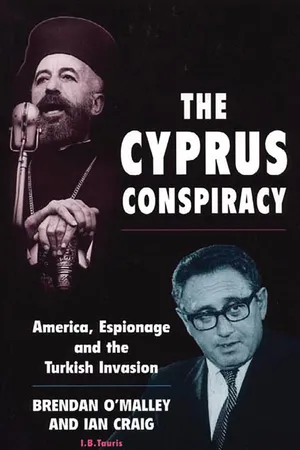

Their remarks followed Cabinet concern that the nationalist emotions which had long rumbled below the surface in Cyprus were being channelled into a potentially powerful movement under a new Greek-Cypriot leader, Archbishop Makarios, and might one day erupt. But, when ministers asked if the heat could be taken out of the situation by promising a review of the island’s status in ten or 12 years’ time, the military chiefs were adamantly opposed.

During the First World War Britain had offered to hand Cyprus over to the Greeks if they joined the battle against the Kaiser. But since then the strategic value of the island as a military base had risen dramatically due to Western Europe’s fast-deepening dependence on Middle East oil and the threat to that lifeline from nationalism and the Soviets. Situated 40 miles from the southern coast of Turkey and 70 miles from the Lebanon, Cyprus was also seen as a vital base from which to prevent the right flank of NATO being turned by Eastern Bloc forces in a Third World War.

The production of crude oil in the Middle East increased from 6 million tons in 1938 to 163 million tons by 1955. Oil from the two other significant producers, the United States and Venezuela, was mainly consumed in the Americas. The Soviet Union, too, produced its own oil, but there was little exportable surplus. Consequently, Europe relied heavily on Middle East supplies to fuel its economic recovery. The region supplied two-thirds of Britain’s needs and contained 65 percent of the world’s known reserves, which implied that Western economies would come to rely on it still further as they expanded in the future. Though the oil was produced mainly in Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, Iraq and Iran, the export of oil from the region involved other states – Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Egypt and Israel – through which supplies were carried by pipeline (41 million tons a year by 1956) or, in the case of Egypt, by ship via the Suez Canal (77 million tons a year) and on through the Mediterranean to Europe. The production, transportation and sale of Middle Eastern oil were important for Britain’s balance of payments and the gold and dollar earnings of the sterling area. Even US companies carried out their work in sterling, so the uninterrupted operation of their work was also important to Britain.2

It was fortunate for Britain that such an important resource was being developed in a region over which it had extensive influence. Britain had controlled Egypt since 1881 and, after the rolling back of the Ottoman empire in the First World War, secured League of Nations mandates over Iraq, Transjordan and Palestine, while France was given mandates over Syria and Lebanon. Though not making them colonies, the mandates made the Arab states subordinate to British and French interests – and the Arabs felt cheated of their independence. By degrees Britain made formal concessions to nationalist pressure, but did not give up its real influence. Iraq, for instance, gained independence in 1932, but Britain kept two military bases at Habbaniyah and Shaibah, near Basra. Transjordan was given independence in 1946, but under a king who had been installed by the British and an army led by British officers. Britain was also given the use of two air-bases at Amman and Mafraq.

Britain’s relationship with Iraq, Jordan and a handful of Persian Gulf states – Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar and the Trucial sheikhdoms – was therefore one of mutual dependence. The Arab rulers gave Britain the use of military facilities or, in the case of the Gulf states, control over foreign relations and the granting of oil concessions, in return for guarantees of military protection against aggressors or internal agitators.3 This afforded Britain the means of maintaining a stable, if undemocratic, order in which its economic interests could continue to operate and develop unhindered, and in which British assets could be safeguarded.

Up to the early 1950s, the flagship of this system of overseas defence was the Middle East military headquarters at Suez. In addition to guarding the Suez Canal, a vital strategic waterway, the Suez base maintained a strategic reserve of up to 80,000 troops, which could be rapidly redeployed to reinforce British garrisons and airfields in the Levant and the Persian Gulf. But, at the very time when Britain’s influence and economic interests were being threatened by a rising tide of nationalism, the agreement which permitted the British presence at Suez was coming up for renewal and was unlikely to be renegotiated. The only alternative site was Cyprus.

After oil, the second factor which gave Cyprus a new military significance was the threat of Soviet expansion. During and since the war, a huge swathe of Europe had fallen to the communists, creating a bloc of pro-Soviet regimes, many of them established through brutal oppression, which extended from the Baltic to the Balkans, virtually cutting the continent in two. The Soviets began with the annexation of Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belorussia, the remainder of Ukraine, and Moldavia. By 1950, Poland, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Rumania, Bulgaria and Albania had become Stalin’s satellites. In 1948 the Soviets challenged the West directly by blockading Berlin and, most alarming of all, in 1949 they exploded their first atomic bomb. As Britain’s wartime leader Winston Churchill had warned, an ‘iron curtain’ was descending across Europe, and the Soviets seemed bent on ‘indefinite expansion of their power and doctrines’ wherever the opportunity arose. The British feared that the Soviets would next try to sweep through southern Europe, dealing a death blow to western democracy and shrinking British influence irretrievably. The next in line for communist takeover in the south was Greece, where after the Second World War a civil war raged for four years between communist forces, backed by Albania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia, and nationalist forces, supported first by 16,000 British troops and later by the Americans. Turkey was also in Soviet sights, because of its enormous strategic value: in the West it straddled the Dardanelles, the only sea passage between the Soviet Union and the Mediterranean, and in the east it blocked one of two routes by which the Soviets could advance into the oil fields of the Middle East (the other being through the Zagros mountains of western Iran).

In a secret memo to the British Cabinet’s Defence Committee in 1946, Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin stressed that the British presence in the Mediterranean was vital to the country’s position as a great power.

The Mediterranean is the area through which we bring influence to bear on southern Europe, the soft under-belly of France, Italy, Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey. Without our physical presence in the Mediterranean, we should cut little ice with those states which would fall, like eastern Europe, under the totalitarian yoke. We should also lose our position in the Middle East (including Iraq oil, now one of our greatest assets).4

The Soviets had already been at work in Iran, a major oil supplier, where they tried to set up a communist government in the northern part of the country in 1945 and backed an attempt to assassinate the Shah in 1949. If Stalin controlled the Middle East, he would have had the power to bring Western Europe to its knees by cutting off its oil lifeline, as Adolf Hitler had secretly planned to do if Russia had fallen in the Second World War.5

Cyprus had a key role to play in keeping the Russians out of the Mediterranean and the Middle East through Britain’s commitment to the defence of Turkey, under the Anglo-French-Turkish treaty of 1939 and, from 1951, under the North Atlantic Treaty. The chiefs of staff noted in 1951: ‘Both on land and in the air Turkey is an integral part of the Middle East strategical area; a rapid collapse of Turkey in the face of Russian aggression would be disastrous to Allied plans for the defence of Egypt.’6 They were anxious to build up a Middle East defence alliance under British auspices, of which Cyprus would be the hub, as Suez was too far south to support defence facilities in the Northern Tier, the rim of mountainous countries to the north of the Levant and the Persian Gulf which provided a land barrier between them and the USSR.7

Bevin recognised that the Americans, while important allies, represented an additional threat to British influence in the region as economic rivals. However, Britain’s straitened circumstances after the Second World War forced an ambivalent policy towards the United States, encouraging the Americans to take responsibility for defending Western capitalism where Britain could not afford to, while trying to maintain maximum British influence over areas of key interest such as the Middle East. The Americans had their own agenda. They were happy to spend billions of dollars propping up Western European economies that provided a captive market for American exports, and to lead their collective defence under the newly-formed North Atlantic Alliance. However, while in some places they saw the British empire as a useful barrier to the spread of communism,8 in other parts of the world they rejected it as an undesirable obstacle to free trade, and encouraged political nationalism by championing self-determination on the world stage.

Part of the price Washington exacted for supporting Britain in the Second World War was the joint declaration in 1941 by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and the US President Franklin D Roosevelt, known as the Atlantic Charter. In it they declared their respect for ‘the right of all peoples to choose the form of government under which they will live; and… to see sovereign rights and self-government restored to those who have been forcibly deprived of them’. The charter was seen by many colonies – which were contributing troops and resources to the war effort – as a firm commitment to self-government for ‘all peoples’. However, a month after the declaration Churchill disingenuously claimed that the references to the rights to self-government were meant to apply only to the states occupied by Nazi Germany, not the crown colonies. The resentment this caused only inspired more support for nationalism. Churchill seemed to expect the colonies to accept that the principles they were helping Britain fight for during the war would be denied them once victory was achieved.9

By 1947 Britain was forced to quit India. Independence for Burma and Ceylon followed a year later. The new-found freedom in Asia inspired nationalist movements in the Arab world, challenging Britain’s control of oil and the oil routes. A campaign of violence forced the British to abandon their mandate over Palestine in 1948, leading to the establishment of a Jewish state. This provided no satisfaction for the Arabs and, alarmingly for Britain, the next thrust of their nationalism came in Egypt.

Since the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty, signed by Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden in 1936, Britain had kept a large number of troops in Egypt and retained exclusive control of the Suez Canal Zone, giving her an important strategic base and ensuring free passage along the canal, essential as a trade route to the Far East and, more recently, as a shipping route for oil. But the Wafd movement was voted into office in 1950 on an anti-British ticket and the new prime minister, Nahas Pasha, opposed the Treaty. Cyprus was the only other base suited to the task.

Hard on the heels of Pasha’s victory, Britain lost its virtual control of the oil industry in Iran (or Persia as it was still known by many), which supplied most of the West’s oil. The new nationalist leader, Dr Muhammad Musaddiq, nationalised the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC), in which the British Government was the majority shareholder. The company ceased operations, virtually bringing Iranian oil exports to a standstill.

Musaddiq’s action also emboldened Pasha. In October 1951, he decided unilaterally to end the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty governing the Suez base without negotiations. At the same time Fedayeen guerrillas carried out attacks on British garrisons in the canal zone. In one counter-attack, British troops killed 50 Egyptians and wounded 100, which led to anti-British riots by violent mobs in Cairo. It seemed clear Britain would not now secure even its limited goal of permission to use the base in international emergencies once the troops had gone and to leave a skeleton force there to keep the installations ready. The West took this setback so seriously that the Americans, despite their professed anti-imperialism, intervened six months later, secretly using the CIA to help General Neguib topple the Cairo regime, and King Farouk. Nevertheless, Egypt and other Arab states spurned the offer to join a proposed regional military alliance against Russia similar to NATO. As the storm clouds of Arab nationalism gathered, the realisation dawned in London that Cyprus, as Britain’s only colony in the region, and with its airforce base and military facilities, would soon be the only guaranteed means of protecting Britain’s position in the Middle East and the Persian Gulf. At the end of 1952, the Cabinet agreed to switch the headquarters of Britain’s Middle East forces from the Suez base to Cyprus.

Even as preparations for the changeover got under way, the Cyprus facilities proved vital during a covert operation against Musaddiq in Iran in 1953. The operation had been left in the hands of the CIA in Tehran. A wireless link via RAF Habbaniyah in Iraq kept the agents in contact with British military headquarters on Cyprus. The plan, suggested to the United States by Britain, involved the recruitment by the CIA of around 6000 anti-Musaddiq Iranians for a $20 million pay-off. But it was betrayed, and the US State Department lost its nerve, sending orders for its men to get out quick. All would have been lost, had it not been for British intelligence, which controlled the communications link with the CIA agents from facilities on Cyprus. MI6 agent Christopher Woodhouse received the State Department’s pull-out signal, but delayed sending it on to Iran. The CIA officers did not move out, and chaos reigned until 19 August, when the CIA’s agents stormed Tehran Radio and announced that General Zahedi was the new Prime Minister. After violent pro-Shah demonstrations, Musaddiq fled.10 A compromise was reached in which Iranian oil remained officially nationalised but a consortium of eight Western oil companies was able to buy all the oil it wanted for 25 years.

The West had got its oil back. But the fact that the nationalisation, on whatever terms, had been upheld was yet another green light for nationalists elsewhere and, ironically, the biggest challenge came from Colonel Nasser, the real leader behind the US-backed coup in Cairo in 1952. He took control of the Government from General Neguib in February 1954, and by July had forced Britain to agree a total withdrawal from the Suez Canal base within 20 months.

The switching of Britain’s Middle East military headquarters to Cyprus had to go ahead swiftly. The island was also to become the new home for MI6’s regional base, controlling MI6 stations at Beirut, Tel Aviv, Amman, Jeddah, Baghdad, Tehran, Basra, Damascus, Cairo and Port Said.11 The island also housed important early-warning radar and electronic spying stations. The intelligence gathered was shared with the Americans under a secret pact drawn up in 1947 called the UKUSA Agreement. Australia, Canada and New Zealand were also members of the UKUSA pact, each member being allotted a different area of the world to gather intelligence from – to avoid duplication. By 1955, Cyprus assumed even greater importance as the dream of a British-led strategic alliance in the Middle East was realised with the signing of the Baghdad Pact, comprising Britain, Turkey, Iraq, Iran and Pakistan.

The pact formally committed Britain to the forward defence of the region, a defence in which nuclear bombs and the Cyprus air-bases played a crucial part in deterring Soviet expansion. A Russian attack on the strategically vital oil fields could come from one of two directions: through Turkey and northern Syria into Iraq, or via Iran and through the mountains separating it from Iraq. Britain was now committed to countering both threats under its obligations to NATO and the Baghdad Pact and Cyprus – geographically better placed than the Suez Canal base, which was too far south – provided the headquarters and platform from which such operations would be launched. The Times reported, ‘In the event of a Russian invasion through Persia, the Cyprus airfields would be necessary for the support of the ground forces in Iraq. The Middle East Land and Air Forces HQ and the brigade group being formed in Cyprus would become the nucleus of our defence against such an invasion.’12 The vital element in those forces was the bomber squadrons operating from Cyprus, which secret British Cabinet minutes said would be capable of delivering a heavy counter-blow with nuclear weapons.13 Nuclear bombs could be used to hold back attacking forces in the mountains long enough to allow a defensive front to be set up in Iraq. An attack on Iran and then Iraq, which Britain was pledged to defend and with whom Turkey was allied, would inevi...