![]()

1

Opium: a Drug in Motion through Time and Space

Opiates are derivatives of opium1 and are among the most widely used drugs in the contemporary world, mostly as pain-relievers but also as so-called recreational drugs. Opiates, however, are the only true narcotic drugs since they cause stupor, induce sleep and relieve pain – as the etymology tells us. Hence, morphine, the principal alkaloid of opium, is an analgesic and a sedative that has an effect on the central nervous system, whilst cocaine, an alkaloid obtained from coca leaves, is a topical anaesthetic which, used as a stimulant, provokes euphoric effects. Under international legislation on mind and body altering substances,2 yet regardless of their respective effects or potency, opiates can be divided into licit and illicit drugs. Thus morphine is widely used as a licit substance in modern medicine, whilst heroin is now mostly consumed as an illicit product.3

The exact geographic origin of the opium poppy still puzzles botanists, historians, and geographers alike but the plant proved itself able to adapt to most ecological environments and spread across all of Europe and Asia and can now also be found in both North and South America, Australia and even Africa, growing under diverse climates and on extremely different soils (Chouvy, 2001, 2002a). As with other cultivars – such as Nicotiana tabacum (tobacco) or Erythroxylon coca (coca) – Papaver somniferum stands out because no truly wild population or specimens exist. This suggests that the history of the opium poppy is clearly linked to the history of human settlement and to cultivation, prompting questions about the symbiosis that developed between the plant and humans, and indicating a very old selection process of drug plants by humans over many thousands of years.

One cannot understand what has most likely been a long and complex relationship between human societies and the opium poppy if the geographic origin and the history of the plant are not explained at least in some detail. As A.-G. Haudricourt and L. Hédin stressed, ‘The narrow dependence of Man and his crop plants . . . can be well understood only if one constantly keeps in mind the conditions under which the vegetable varieties and species occur and are distributed geographically’ (Haudricourt and Hédin, 1943: 21). As for the nature of this relation, it is particularly well expressed by biologist and pharmacognosist J.-M. Pelt, who wrote that the ‘drug sticks to Man like the skin to his flesh’ (Pelt, 1983: 14).

THE OPIUM POPPY AND MANKIND

There are differing ideas about the botanical evolution of the opium poppy but all varieties of Papaver somniferum appear to have developed in and around human settlements, either in the areas created and maintained by people or on the peripheries, on dumping grounds and around cultivated fields, for example. One idea, put forth by J.M. de Wet and J.R. Harlan, is that selection would have operated according to a double process of artificial selection and natural selection (Wet de, Harlan, 1975: 99–107). Seeds coming from the cultivated wild plant would have escaped and colonized peripheral spaces modified or disturbed by human activity. Some ‘escaped’ poppies would then have adapted gradually to continuing human disturbance of its habitat.

Human settlement and the beginnings of agriculture probably benefited the opium poppy by enlarging the habitat most favourable to its development, together with other weeds no doubt, some of which also had psychoactive properties and which often entered opium-based preparations. This was the case for Datura stramonium L. (often known as Jimson Weed), for example, which was part of the Greek nepenthe, the potion used to induce forgetfulness of pain or sorrow.

Given its beauty – its bright and colourful flowers – people must have noticed the poppy at a very early stage. Its many useful properties – food, oil, medicine, fodder, recreation and, or, ritual – not to mention its facilitated growth in and around human settlements, must have ensured the continuing association with people and its spread along transcontinental migration routes.

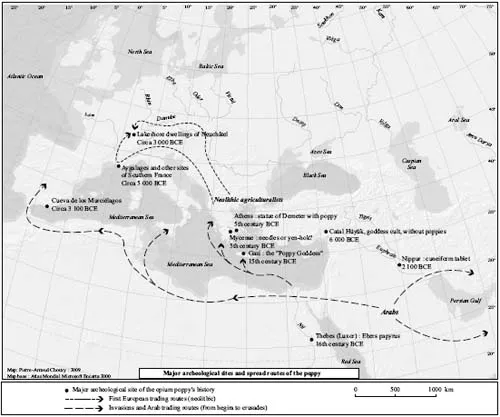

THE GEOGRAPHIC ORIGIN AND HISTORIC SPREAD OF THE OPIUM POPPY (MAP II)

Archaeological evidence has led specialists to believe that the opium poppy probably originated somewhere between the Western Mediterranean and Asia Minor. It is, however, on the Neolithic lakeshore dwellings of Neuchâtel, Switzerland, that some of the oldest paleobotanical remains of opium poppy seeds and capsules have been found. Fossil evidence has also been found in Cueva de los Murciélagos, in southern Spain, but no similar findings have been made in the Eastern Mediterranean or in Asia Minor (Merlin, 1984: 173–5). In his book, On the Trail of the Ancient Opium Poppy, M.D. Merlin concludes: ‘Although most of the fossil evidence for the opium poppy comes from west central Europe, we do have a small amount of direct evidence from other Neolithic and Bronze Age locations in southern Spain, the Rhineland, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and perhaps Turkey’. He then suggests that ‘the opium poppy was spread out of central Europe and down into the eastern Mediterranean region during the later part of the prehistoric period (i.e., the late Bronze Age) (Merlin, 1984: 282–3).

Map II: Major archeological sites and spread routes of the poppy.

It is now commonly accepted that the opium poppy probably originated in Europe and was part of the trading activity of the earliest migrations between the different peoples of Europe and Asia. Indeed, it has been suggested that seeds of Papaver somniferum, and even some opium, may have been included in the extensive trading undertaken by the Sumerians, whose commercial network reached all the way to the Mediterranean to the west and the Indian subcontinent to the east. Thus, poppy seeds as well as opium must have been exchanged for thousands of years, by both sea and land, making opium use an ancient practice in various regions.

There is no doubt that the Egyptians traded opium – the so-called opium thebaicum, for instance, whose reputation was well established in the thirteenth century BCE (Latimer and Goldberg, 1981: 17). Indeed, it is probable that it was the Egyptians who were responsible for the spread of opium poppy cultivation within Europe, by introducing it to the Greeks. In southernmost Europe, the use of opium clearly declined after the fall of the Roman Empire (fifth century CE), only to reappear much later with the return from the crusades (thirteenth century CE), thus underlining the role of the Arabs in the geographical spread of opium.

It is generally believed that the Arabs played the major role in spreading the opium poppy and opium-related knowledge to the rest of the world. They early understood and exploited the commercial potential of opium and spread its consumption all the more easily as their empire rapidly expanded. Trade, which was accompanied by the spread of Islam, formed an integral part of their traditions. Where the Arabs went opium followed, whether by caravan or aboard dhows, whose most skilful navigators benefited from the monsoon winds which the Phoenicians had sailed before them.

The Arabs supposedly introduced opium to India, after having conquered Spain, Egypt, Asia Minor, Turkistan, Persia and certain parts of India in the seventh century, although some suppose that Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE) had already introduced it ten centuries earlier. In India, however, the first known reference to the opium poppy dates only from 1000 CE, whereas one has to wait until 1200 CE to find opium mentioned from an explicitly medical point of view (Husain and Sharma, 1983: 25).

It is again the Arabs who are reputed to have introduced opium and the knowledge of its uses to China in the eighth century, in spite of the fact that there are Chinese texts referring to its use as early as 987 BCE and again in the third century (Booth, 1998: 104). These texts hardly leave any doubt that opium was known and used in China before the Arabs ever traded in it. However, the leading role that the Arabs took in the spread of the opium poppy is clear if one only looks at the etymological similarities of ‘opium’ in many languages: afiun in Arabic and Persian, opium in French and English, opos or opion in Greek, afium in Turkish, ahipen in Sanskrit, aphin in Hindi. As for the Chinese Fu-yung (ya-pien), linguists maintain that it also comes from the Arabic afiun.

The Arabs might not have introduced opium into China but they undoubtedly traded in it, at least to make up the shortages in Chinese production. However, with the decline of Arab influence and the unprecedented development of the European maritime trade, the commerce in opium was taken on by the Venetians after the lagoon city became the main centre of European trade (from the thirteenth century on). At that time opium was highly prized in Europe, since all the great navigators were charged, among other things, with bringing back the famous panacea from their voyages. Hence the Portuguese took over the opium trade with Vasco de Gama (1460–1524). They bought opium in India, where poppy cultivation was strongly encouraged by the Mughal emperors for the substantial income it brought them. Then, by settling in Macao in 1557, the Portuguese permanently took over from the Arabs. As for the famous Indian opium from Bengal and Malwa, it quickly became highly coveted by the Dutch and the British, who spread its use in Java and in China, respectively.

It is, however, only when the European maritime powers, as a result of their great expeditions, initiated an era of globalization, that the opium trade took on a brand new dimension: interpenetration and interdependence of the world’s markets were to inaugurate new dynamics and to lay down the conditions for the global drugs trade.

Indeed, with hermit Romano Pane allegedly being the first Westerner to witness tobacco inhaling in fifteenth century Hispaniola, a brand new era in the diffusion of opiates began: beyond tobacco it was opium which could now be smoked, like hashish, and later, cocaine or even crack. The introduction by the Portuguese and the Spaniards of the pipe and tobacco in Southeast Asia, whose use was later taken over and spread by the Dutch, spurred opium consumption in a way that the British quickly and skilfully exploited. Opium was efficiently produced and traded by colonial monopolies to ensure the profitability of their colonies and, at least for the British, to balance their trade deficit with China. Fearing that payment for Chinese imported goods (tea consumption was growing fast in Britain when only China produced the leaves) would deplete their silver reserves, the British resorted to opium, a product of their Indian colony, as a means of payment: ‘A triangle traffic developed in which opium smuggling yielded the silver later used to buy tea legally, which was then shipped to London’ (Meyer and Parssinen, 1998: 9).

The first shipment of Indian opium arrived in Canton in 1773, eventually leading China to mass addiction. Although opposed by the Chinese rulers, the trade continued unabated for decades until two so-called ‘Opium Wars’4 (1839–42 and 1856–60) between the British, who wished to maintain the trade, and the Chinese who tried to put an end to it. The treaty of Nanjing (1842), which ended the first war, gave Hong Kong to the British. Hong Kong would go on to become the world’s main heroin hub in the twentieth century. China, confronted with exploding opium consumption, eventually fostered local poppy production as a way of balancing its own growing trade deficit: China, as the biggest opium-consuming country ever, then became the world’s leading producer as well (35,364 metric tonnes in 1906: 85 per cent of world production). The Treaty of Nanjing also included a provision for extra-territoriality: i.e. ‘the right for British subjects in China to be judged by their own consuls and tried under their own legal system [. . .]. The privilege, later granted to other foreign powers, created enforcement-free safety zones used by traffickers when drugs once again became illegal in twentieth-century China’ (Meyer and Parssinen, 1998: 10–11).

Beyond its strictly financial dimension – the fact that it was deeply integrated into global colonial trading together with tea, sugar, silver, and cotton – the opium trade entered a system in which British capitalism transformed certain substances ‘from upper-class luxuries to working-class necessities’. Indeed, opiates, ‘like coffee, or chocolate or tea [. . .] provide stimulus to greater effort without providing nutrition [. . .]’ (Mintz, 1985: 186). In Asia, where most of today’s illicit opium and heroin are produced, ‘opium prepared the ground for capitalism by creating mass markets and proletarian consumers while undermining the morale and morality of elites’ (Trocki, 1999: 53). In Asia, ‘opium, both in the case of capitalist development as well as in the case of colonial finance, served to tighten up those key areas of “slack” in European systems and facilitated the global connections that in effect, were the [British] empire’ (Trocki, 1999: 59). Indeed, as Carl Trocki documents, Chinese labour in the colonial economies of Southeast Asia had two advantages: it enabled production by the coolies (opium consumption being used both to dull the worker’s pain and as a prophylactic against diarrhoea and fever caused by dysentery, malaria, typhoid and intestinal parasites); and provided revenue (in the form of taxes) available from opium farms (or monopolies), as only Chinese were allowed to smoke opium. As a matter of fact, the coolies’ pay was taken back by the colonial system through the opium farm system: ‘opium was not peripheral to the system [. . .] but rather it was central [. . .]. If the cost of employing labor were not recaptured by the capitalist and recycled, as it were, there would have been no profit.’ (Trocki, 1999: 144–7). As Timothy Brook and Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi put it, opium ‘gave foreign powers the financial wherewithal to make colonial empire-building feasible’ (Brook, Wakabayashi, 2000: 1). However, it is also true that colonial empire-building clearly made large-scale opium production, trading and consumption feasible.

Having been used to make the European colonies in Asia viable and even profitable, the opium poppy then spread on a global scale: it accompanied Chinese immigrant workers (coolies) to the Americas, rendered Japanese expansionist policies in septentrional China (Manchuria) lucrative and developed on the successes of the modern drug traffickers.

Today, this narcotic plant thrives to a greater or lesser extent across the surface of the entire planet: in Asia of course, where for decades the Golden Triangle (Burma, Laos, Thailand) and the Golden Crescent (Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan) have been the two most important areas in the world for illicit opiates production; but also in Europe (France, Spain), India, and Tasmania, where one can find licit crops for the pharmaceutical industry; in Africa, where the poppy has asserted its presence along the Gulf of Guinea ; and finally in North, Central and South America, where Mexico is one of the world’s most important producers of illicit opium (and heroin), and where certain Andean states, already involved in coca growing, have witnessed an increase in poppy cultivation, a testament to the interest that drug traffickers take in diversification.

THE OPIUM POPPY, FROM EARLY USE TO PROHIBITION AND CRIMINALIZATION

Asia, where most illicit – as well as licit – opium is produced, has a long association with psychoactive substances. Many of them – cannabis, opium, datura, etc. – have been found throughout the continent for centuries and sometimes thousand of years, and have been used, either separately or in combination, for a variety of purposes, as in India’s saddhus rituals, where spirituality can be accessed by way of hashish consumption. Different societies established traditional uses for such substances (or so-called ‘drugs’) such that they have become part of social codes (as in Persia), religious rituals (as in India), and local pharmacopoeia (as in China). Centuries ago, before the pipe was introduced into Asia by the Europeans, opiates were consumed by ingestion, by way of opium poppy decoctions or by eating opium, sometimes in sophisticated and even tasteful preparations. Such consumption was traditional, both ritually and medically. With opium smoking, a recreational use emerged both in Asia and Europe in the eighteenth century (later in North America) and gave rise to a fully-blown social and economic phenomenon.

Addiction was facilitated when the intake of alkaloids was made easier, echoing to some extent what happened when tobacco became available in ready-made cigarettes (North Carolina cigarettes had even been marketed in China to help wean the Chinese from opium) (Courtwright, 2001: 112–22). Addiction to narcotics was further facilitated by the discovery of the first alkaloid – morphine (1805–6) – by the invention of the hypodermic syringe (1851), and by the rapid advances in the pharmaceutical industry that led to the production of heroin (by Bayer in 1898). In fact, ‘opium made the same transition earlier accomplished by sugar and tobacco, from an exotic chemical to a fully “capitalist” drug commodity’ (Trocki, 1999: 58). The advent of injecting drugs by syringe not only potentially led to severe addiction but also to contracting blood-borne diseases such as hepatitis and HIV/AIDS.

Now more than ever, the modern trade in illicit drugs is shaped and stimulated by mercantilism, even more so as it grows on the fertile and complex terrain of both poverty and armed conflict. In fact, a direct relation between illicit drugs production, poverty and war appears to exist (Chouvy, 2002a). Illicit drug production and drug trafficking have always, it would seem, been the outcome of both economic and political events.

However, the trade in narcotics was deeply disrupted when addiction became a social (even religious) issue in Western countries, especially in the United States, where the Chinese had brought opium smoking with them in the earliest days of the gold rush and where anti-Chinese sentiment swept California as early as the mid-1870s: on 15 November 1875, in San Francisco, an ordinance made it a misdemeanour to keep or frequent opium dens, thus calling the first shot in the prohibition of certain drugs in the United States. As would so often be the case in more than a century of glob...