eBook - ePub

The Water Crisis in Yemen

Managing Extreme Water Scarcity in the Middle East

- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Christopher Ward provides a complete analysis of the water crisis in Yemen, including the institutional, environmental, technical and political economy components. He assesses the social and economic impacts of the crisis and provides in-depth case studies in the key management areas. The final part of the book offers an assessment of current strategy and looks at future ways in which the people of the country and their government can influence outcomes and make the transition to a sustainable water economy. The Water Crisis in Yemen offers a comprehensive, practical, and effective approach to achieving sustainable and equitable management of water for growth in a country whose water problems are amongst the most serious in the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Water Crisis in Yemen by Christopher Ward in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Sustainable Development. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

YEMEN AND ITS WATER RESOURCES1

Part I of this book sets the scene. Chapter 1 introduces the geological origins and endowments of Yemen, and its physical and human geography. Chapter 2 sketches out the history of Yemen and its social and political background up to today. Chapter 3 tracks Yemen’s path towards the development of a modern economy. In Chapter 4 Yemen’s water resources are described and Chapter 5 then discusses the numerous ingenious and laborious ways in which Yemenis have, over the last 5,000 years, developed these resources.

CHAPTER 1

PHYSICAL ENDOWMENT1

1.1 Formation of a land

The earth is 4.6 billion years old, formed through accretion of floating dusts. The geology that now defines Yemen’s landscape and its minerals and water-bearing capacity began to emerge more than a thousand million years ago and developed over hundreds of millions of years. Change has been continuous, as the rocks that progressively formed the land were cooked in the depths of the earth, ground down by erosion, wracked by ice, rearranged across the face of the planet, merged with and parted from various early continents, crushed by irresistible tectonic pressures, and finally worked into landscape by the actions of nature and the hand of man.

The Arabian Peninsula is part of the African–Arabian plate

In the Pre-Cambrian era, at least 500 million years and perhaps more than a billion years ago, the crystalline basement rock that now makes up the foundation of the south-west corner of Arabia formed as part of the African–Arabian plate. The plate’s upper crystalline crust was formed through 300 million years of continental crustal growth between 850 and 550 million years ago. The plate underwent intensive folding and metamorphosis. Even at this time, life may have been present – minute fossils of bacteria go back more than 3 billion years.

In the Palaeozoic – some 300 million–500 million years ago – the basement rock eroded and warped. Eroded sediments accumulated, deposited in layers by ancient seas as they expanded and receded, covering the basement rock. During the Jurassic era of fossils and dinosaurs, 150 million years ago, sediments continued to accumulate, and subsidence created the organically rich shales of al-Jawf, with their petroleum-bearing potential.2

Later, in the Mesozoic Cretaceous era – ‘the age of reptiles’ – 100 million years ago, the African–Arabian plate collided with the Eurasian plate. The south and west of the Arabian Peninsula was lifted up, and the Pre-Cambrian crystalline basement was partly exposed and broken into blocks, forming the Arabian shield with its steep western sides and gentler inclines to the north-east. The crystalline basement rock was depressed in the north and east and subsequently overlaid by sediments formed from the erosion of other rocks. These old sandstones, often several hundred metres thick, form the porous, water-bearing rock that today holds Yemen’s deep aquifers.

During the late Cretaceous and the Tertiary periods, volcanoes threw up hot infusions and the lava extruded to cover the basement. At the start of the Tertiary, the earth suffered two cataclysmic events. First, an asteroid smashed into the Yucatán Peninsula 65 million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs. The subsequent ‘fever period’ about 56 million years ago warmed the earth by as much as 20°C, a massive release of greenhouse gases drove up a carbon spike, and hoofed mammals and primates fled north from the scorching heart of the equatorial latitudes. Then, 65 million–30 million years ago, the Arabian plate drifted north-eastwards, separating from Africa and opening the rift valleys that we know as the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden. Pressure north and east caused folding, forming the Zagros Mountains in Iran. The mountains of Yemen suffered intensive block faulting, with vertical displacement of up to 2,000 m.

Finally, in our own Quaternary period, new volcanic activity began (and continues to this day), producing basaltic eruptions. The present-day drainage systems developed – the wadis and alluvial and coastal plains. Sands and gravels laid down during this time form Yemen’s alluvial aquifers, and the action of wind eroded rocks and laid down Aeolian sedimentary deposits.

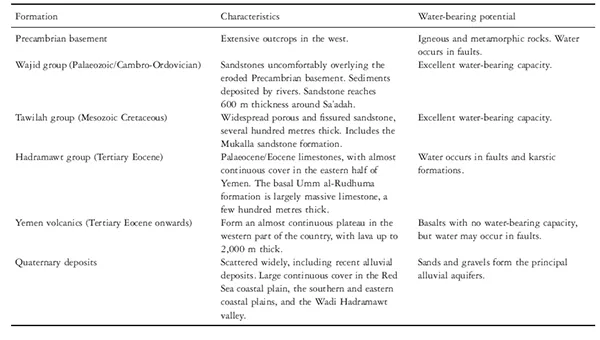

The result of these billion years of activity is an old, weathered geology, a mountainous country with steep western sides and gentler inclines to the east. The crystalline basement is partly covered by sediments and volcanic rocks, intersected by wadis and surrounded by alluvial plains. These geological formations determine Yemen’s hydrogeology today (Table 1.1).3

1.2 Climate

Sunshine and the weather

The weather in Yemen is pleasant, although the coast is excessively hot and humid in summer

Yemen is a sunny, sub-tropical, arid to semi-arid country. High-pressure systems with an inversion above and stable air beneath produce clear skies with high levels of sunshine averaging six to nine hours a day. Even in the rainy summer months, the sun shines six hours a day on average. Average temperatures are in the range 13–20°C in the highlands and 20–30°C on the coast. Temperature variations follow elevation. Characteristically for arid areas in the sub-tropics, there is a large difference between day and night temperatures.5

Table 1.1 Geological formations and water-bearing potential4

Figure 1.1 Yemen’s old weathered geology, showing drainage systems and wind-eroded rocks (Jol plateau in Hadramawt). Photograph courtesy of Matthias Grueninger.

The Yemeni highlands have a blessed climate where neither heating nor cooling is needed in the house. A typical winter day in the highlands is pleasant: no rain, dry air, clear cloudless blue skies, warm in the sun but not too hot. Only the dryness may be irksome to the skin. At night it becomes chilly as temperatures drop towards zero. Yemenis complain and wrap their heads about with scarves. In the summer the weather changes – but not for the worse. A summer day in the highlands is clear and hot in the morning and the landscape luminously well washed. Clouds form towards midday and by late afternoon they produce rain, sometimes in intense storms. In the evening the land steams and the going is muddy underfoot. At night the skies clear again.

On the coast, a typical day would be dry, warm and humid in the winter, and dry, hot and very humid in summer, with little variation day or night. In the margins of the desert, the climate is dry and hot by day with low humidity, and significantly colder at night.

Rainfall

The Yemeni highlands enjoy seasonal rainfall

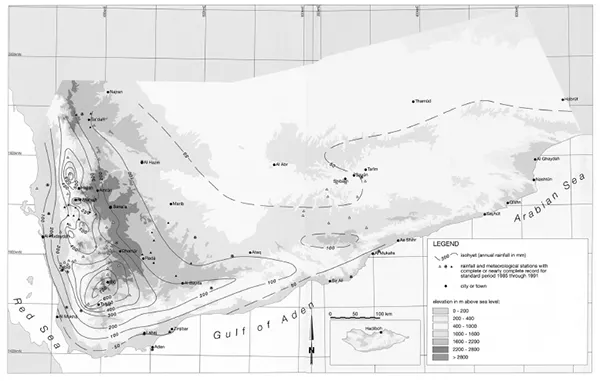

Much of Yemen has an arid (<600 mm annual precipitation) to hyper-arid (<100 mm) climate. Average annual rainfall above 250 mm is only found in the southern and western highlands, with a maximum near Ibb of 1,500 mm (Figure 1.2). Two factors produce higher rainfall in the highlands: the trade winds that blow in moist air from the Indian Ocean, and the steep increase in elevation. Moist air passes over the coastal plains, where the humidity is often intense but without much rain. When the air is forced up over the mountains, it cools and the rain then falls. Ibb enjoys so much rain because of its high elevation and because air masses move in from both the Gulf of Aden and the Red Sea.

By contrast with the Arab countries around the Mediterranean littoral, where rain falls in winter, the rainy season in the Arabian Peninsula comes in summer. This mainly affects Yemen, as precipitation elsewhere in the peninsula is scant. In the Yemeni highlands there are two distinct rainy seasons: the saif (April–May) and the kharif (July–September). The north-west trade winds blow during April and May, entering the Red Sea Convergence Zone and producing the saif rains. Later in the summer, the sun moving north warms the climate and creates a trough of low pressure – the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone. Warm dry air from the north converges with moist air blown in from the Indian Ocean. The convergence drives up the hot moist air and cools it to produce the kharif monsoon rains of July to September. Rain typically falls in one rather short event, rarely longer than an hour or two.

Aridity

It is principally the combination of low rainfall and high temperatures that makes Yemen an arid land

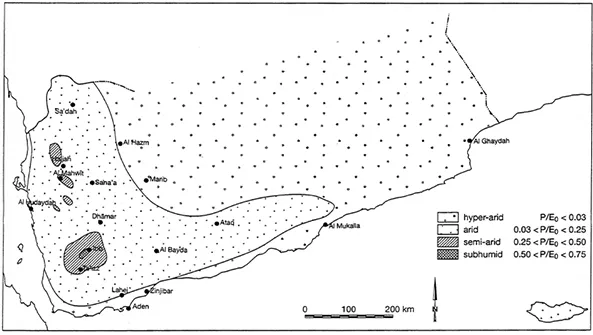

Rainfall alone cannot determine aridity. Evaporation rates determine how much rain is available for use, so aridity is measured not just by rainfall but by the ratio between precipitation and potential evaporation. In Yemen, with its low humidity and high temperatures, potential evaporation is rapid, ranging from 1,800 mm to 2,500 mm. In all cases, potential evaporation is much higher than rainfall, so rain evaporates quickly after falling. On this basis, two-thirds of Yemen is classed as hyper-arid (the deserts and parts of the coastal plain), and most of the rest is classed as arid. The highland areas around Hajjah, Mahweet and Ta’iz are classed as semi-arid. Only small pockets near to Ibb are rated as sub-humid (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.2 Average annual rainfall, period 1985 through 1991. ‘The Water Resources of Yemen: A Summary and Digest of Available Information’, Report WRAY-35, Sana’a, Republic of Yemen, March 1995.

Figure 1.3 Climate zones of Yemen. ‘The Water Resources of Yemen: A Summary and Digest of Available Information’, Report WRAY-35, Sana’a, Republic of Yemen, March 1995.

1.3 Geography

Human geography follows hydrogeography

Historically, population was concentrated in the west of the country, in the valleys, plains and eastern and western margins of the highlands, and on the coast. In so dry a country, centres of population could only develop where water was available. Yemen’s hydrogeography and human geography are closely linked. Even today the largest towns are on the coast or in the highlands in the west.

Geography of the regions

Figure 1.4 shows the broad coastal plains along the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden coastline. Above the Red Sea coastal plain rises the massif of the western Yemeni mountains, strongly dissected by numerous wadis and containing intermontane plateaux. The relief then slopes away east to the desert margins and to the depression of the Ramlat al-Sabatayn desert and the Rub’ al-Khali.

The coastal plains are largely flat, with a hot and humid climate and low rainfall. Economically, the coast has always been important as there are several good natural harbours, including Aden, one of the world’s largest deep water anchorages, and Mocha, the port from which coffee was first exported to the world. The plains are important agricultural areas because the spate flows in the wadis coming from the mountains are diverted for irrigation. Wadi Zabid, for example, has supported irrigated agriculture and a flourishing culture for many centuries. The well-organized mediaeval spate schemes there allowed the city of Zabid its prominence as a place of learning from the early Islamic period onwards. Algebra is said to have been invented there by the mediaeval mathematician, al-Jabr. So civilization follows water, which follows geography and geology.

The mountains and the intermontane plateaux are cooler and damper. The plateaux are mostly around 2,000 m elevation, and the massif rises to the peak of Yeme...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I Yemen and its Water Resources

- Part II Uses and Misuses of Water in Yemen

- Part III Managing Yemen’s Water Crisis

- Part IV The Water Agenda for a New Era

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Back Cover