- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

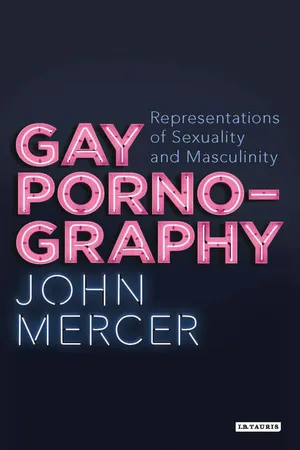

Gay pornography, online and onscreen, is a controversial and significantly under-researched area of cultural production. In the first book of its kind, Gay Pornography: Representations of Sexuality and Masculinity explores the iconography, themes and ideals that the genre presents. Indeed, John Mercer argues that gay pornography cannot be regarded as one-dimensional, but that it offers its audience a vision of plural masculinities that are more nuanced and ambiguous than they might seem. Mercer examines how the internet has generated an exponential growth in the sheer volume and variety of this material, and facilitated far greater access to it. He uses both professional and amateur examples to explore how gay pornography has become part of a wider cultural context in which modern masculinities have become 'saturated' by their constantly evolving status and function in popular culture.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gay Pornography by John Mercer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Contexts and Frameworks

1

Saturated Masculinity

We cannot study masculinity in the singular, as if the stuff of man were a homogenous and unchanging thing. Rather we wish to emphasize the plurality and diversity of men’s experiences, attitudes, beliefs, situations, practices and institutions along lines of race, class, sexual orientation, religion, ethnicity, age, region, physical appearance, able-bodiedness, mental ability and various other categories with which we describe our lives and experiences.

Harry Brod and Michael Kaufman, Theorizing Masculinities (1994:4–5)

This book, then, is concerned with the ways in which masculinities are constructed in and through gay porn, which is a mode of representation that cannot be understood in isolation. Whilst it has always been one of the fundamental tenets of cultural studies that any artefact or practice must be placed in its social, cultural and historical context in order to make sense of it, I have often thought that the narrow specificity that can sometimes frame the analysis of aspects of what has been described through custom and practice as ‘gay culture’ presents challenges for the researcher (and this is as true of my own work as of anyone else’s). At its most extreme, a limited analytical and contextual field of view can easily ossify the chosen object of study. In this regard, I agree with John Champagne’s critique, discussed in the introduction, of some of the issues presented by the close textual analysis of porn films. At the very least, considering gay culture in isolation can lead to a stifling parochialism that sidesteps the wider political significances that can be attached to representations of gay identities and gay desires. That scholars have striven to carve out a demarcated space for the discussion of gay representation is, of course, of vital importance and that this space has become a quite narrow one, at points, is also hardly surprising given that before the late years of the last century, gay culture tended to be regarded as a marginal (or marginalised) interest within academe. In the previous chapter, I have described my own early experiences as a researcher, in order to acknowledge this. My view is that gay culture, however that term might be understood, must be situated within the context of a wider popular culture, not least because so much of what constitutes this ‘gay culture’ is based on interaction with, recycling and reappropriation of aspects of the wider culture.

This matters here because this study addresses a genre and a mode of representation that might at first glance be regarded as paradigmatically an exclusively gay interest and therefore of concern to gay men and a putative ‘gay community’ alone. I believe this to no longer be the case at all. There are a set of circumstances and shifts in cultural attitudes that had already begun by the late years of the 20th century, and which have gained a momentum of their own during the 21st century, that mean that the nature of the ways masculinity is figured and constructed within popular culture and the status of pornographic representation (and gay pornographic representation in particular) has fundamentally changed. These changes, discussed in this chapter, have arisen as a result of a set of cultural and social determinations and have been mobilised by widespread access to global culture as a result of the web and a set of concomitant shifts in attitudes towards sex, sexuality and masculinities that have gathered pace since the start of the 21st century.

One of the significant results of this set of factors is that porn, whilst still a politically charged form of cultural production and consumption in some circles, is no longer either marginal or taboo in any meaningful sense. Furthermore, on the basis of accessibility alone (though this is not the exclusive determinant), gay porn is not an obscure or a narrowly specific and marginal cultural practice, and consequently, in my view, it becomes an especially productive site through which we might explore modern masculinities.

One of the key premises of this book is that, in the developed West at least, masculinity as it is represented and inscribed into culture has undergone a radical transformation during the late 20th and early 21st century. As I will note in this chapter, drawing on the important work that theorists of masculinities have undertaken since the mid-1980s, it has become clear that a singular model of masculinity as it is prescribed and bounded by tradition and normative standards is no longer tenable and that in recent years the evidential basis for this claim has become increasingly compelling. Furthermore, my argument, based on an adaptation of Kenneth Gergen’s terminology, used to describe contemporary identity, is that masculinity is now saturated with meaning. In short, masculinities are a multitude and are represented, likewise, in a multitude of ways, and this is vividly evidenced in the types that populate the fantasy worlds of gay porn.

Masculinity and Popular Culture

Since the advent of the foundational scholarship of the 1970s, and the work of a range of researchers across disciplines during the 1980s and early 1990s – including but not limited to Komorovsky (1976, 2004), Pleck (1980, 1983), Cockburn (1983, 1985), Weeks (1985, 1986, 1991), Brod (1987, 1994), Kaufman (1994), Kimmell (1987, 1995, 2004, 2013), Messner (1995, 1997, 2010) and Hearn (1987), as well as the work of Messerschmidt (1993, 1997, 2000), Buchbinder (1992, 1994, 1998, 2012), Seidler (1989, 1997, 2006), Anderson (2009, 2010, 2012, 2014) and others)1 – it has become an orthodoxy to argue, as do I in this book, that masculinity cannot be meaningfully understood as a monolithic entity and instead that it is more productive, indeed necessary, to conceptualise multiple masculinities. Looming large over these debates, though, and sometimes in a divisive fashion, is the figure of Raewyn Connell and her book Masculinities (1995, 2005) in which she describes the concept of hegemonic masculinity. Connell’s contemporaries had concerned themselves with developing a field of knowledge that challenged a singular model by way of the production of knowledge that uncovered the diversity of experiences of masculinities across generations, class divides and cultures. Whilst not denying the variousness of the experience of men, Connell’s work argued that what mattered was that power relations were at play in the ways in which masculinity is constructed, gender inequality is maintained and thereby patriarchy is perpetuated, by drawing on the Gramscian model of hegemony. Even whilst she notes that hegemony is a ‘historically mobile’ (2005:77) phenomenon and that its ‘ebb and flow is a key element of the picture of masculinity’ (pp. 77, 78), Connell’s conceptual model presumes a dominant masculinity that is shored up by masculinities that she sees as variously subordinate and complicit. As Robert Hanke notes, this hegemonic masculinity is a ‘model of masculinity that, operating on the terrain of “common sense” and conventional morality defines “what it means to be a man”’ (1990:232).2 Connell’s work has had a wide-reaching influence in the field of masculinity studies and beyond and has framed the debate around masculinity for 20 years but it has also attracted some degree of controversy and criticism. This is something that Connell was to address herself when, ten years after the initial publication of Masculinities, she wrote the essay (with James Messerschmidt) ‘Hegemonic Masculinity: Rethinking the Concept’ (2005). Connell’s response is an especially thorough reappraisal of the value and challenges her conceptualisation of hegemonic masculinity presented for the field and she is particularly generous in her thoughtful engagement with many of the scholars who were to take issue with her position. Connell and Messerschmidt conclude the essay with the admission that hegemonic masculinity is a concept that needs to be reformulated by attention to four areas, ‘the nature of gender hierarchy, the geography of masculine configurations, the process of social embodiment, and the dynamics of masculinities’ (2005:847), providing a set of research questions that should frame this work. This is a project that subsequent scholars have taken up, more or less, by either working within the constraints of the model (as in the case of Kimmel) or by proposing alternatives (see Anderson for example). Whilst the directions that Connell points towards are indeed useful, she makes it clear that she is wedded to the core tenets of her model, i.e. a ‘dominant’ hegemonic masculinity alongside what she describes as ‘subordinated and marginalised groups’ (ibid.) and the essay challenges many of the arguments presented elsewhere. For example she focuses some considerable attention on one of the most thoroughgoing critiques of her work, offered by Demetrakis Demetriou in his essay ‘Connell’s Concept of Hegemonic Masculinity: A Critique’ (2001). Demetriou is critical of the ways in which Connell appropriates Gramsci, noting (correctly in my view) that her model of hegemony is ultimately static (though I would argue that this is largely a consequence of the ways in which her ideas have been put to use, and sometimes misuse, by subsequent scholars) and therefore almost by definition not hegemonic at all. He proposes an adaptation of Connell’s model aligned more closely to Gramsci and also to the work of Brian Donovan (another critic of Connell) to propose what he describes as the ‘hegemonic bloc’ that he sees as ‘hybridized’:

Donovan’s studies reinforce the argument developed out of Gramsci’s conceptualization of the process of internal hegemony: that the masculinity that occupies the hegemonic position at a given historical moment is a hybrid bloc that incorporates diverse and apparently oppositional elements.

(2001:34)

This concept of hybridity becomes especially important for Demetriou, who then goes on to use the example of gay masculinity as an example of a masculinity where elements of hegemonic masculinity have become hybridised and assimilated through ‘negotiation, appropriation, and translation into what he still prefers to describe as ‘modern hegemonic masculinity’ (ibid.). Connell, however, remains unconvinced that this hybridisation that Demetriou describes, is indicative of a challenge to hegemony (or indeed to her model):

Clearly, specific masculine practices may be appropriated into other masculinities, creating a hybrid (such as the hip-hop style and language adopted by some working-class white teenage boys and the unique composite style of gay ‘clones’). Yet we are not convinced that the hybridization Demetriou (2001) describes is hegemonic, at least beyond a local sense. Although gay masculinity and sexuality are increasingly visible in Western Societies – witness the fascination with the gay male characters in the television programs Six Feet Under, Will and Grace, and Queer Eye for the Straight Guy – there is little reason to think that hybridization has become hegemonic at the regional or global level.

(2005:845)

Notwithstanding the clear irony that a field committed to challenging a monolithic conception of masculinity should become so dominated by a paradigmatically monolithic theoretical framework, the vigorous and productive debate that Connell’s work has provoked has resulted in conceptual tools that are especially useful for my analysis of masculinities as they manifest in gay porn and the position of gay porn, vis à vis contemporary masculinity and popular culture. Sofia Aboim, for example, summarising the range of terms that have been adopted in recent years to describe the scope and range of masculinities, uses the term ‘plurality’ in more than an adjectival sense:

Plurality is, in my view, an intrinsic feature of any masculinity. It is its formative and generative principle. Therefore any masculinity is always internally hybrid and is always formed by tension and conflict. Any masculinity, as any man, any individual, is plural both in relation to the material positions that locate him in the social world and the cultural references that constitute his universe of meaning and significance.

(2010:3)

These dual notions of plurality and hybridity are helpful in my analysis of the expressions of sexualised masculinity that gay porn offers that are, to use Aboim’s words, generative and hybridised. This is most evident in the web-based materials that are the subject of this study. A particular curiosity that I would observe here though is that whilst several scholars, including Connell and Kimmel (2005:415) and Acker (2004:29), have paid attention to the global conditions of gender and posited a ‘global’ hegemonic masculinity,3 little, if any, mention is made in this research of the potential, as well as the challenges, posed for regional models of masculinity, normative standards and attendant conditions of power by the pervasiveness and global reach of the internet. Indeed, the web too often feels like a blind spot for the major thinkers and theorists in the field of masculinity studies, which inevitably the research in this book aims, in part, to address.

Within the realm of popular culture, it is increasingly common to see proliferating models of masculinity and instances where seemingly conventional ‘dominant’ masculinities (which we are often encouraged to read as variously old-fashioned, redundant or moribund) are supplanted by a panoply of new articulations and iterations of manhood. This of course is not new in and of itself. A historical view of the cultural construction of modern masculinities indicates that far from being static, masculinity is often in flux. Furthermore I would argue that the mass media have frequently played a pivotal role in the articulation and promotion of new modes of masculinity since at least the middle to late 19th century. So Dandyism, and more latterly the figures of the flaneur and the aesthete, were in part, at least, drawn into existence and popularised through newspaper reportage.4 During the 20th century, we can observe a further blooming of models of masculinity through not just the press but also cinema, television and popular music, and this trend seems to have escalated in the 21st century.5 In recent years we can see examples of ‘new’ masculinities that have been brought into view initially through the practices of the media and that have subsequently garnered scholarly attention. The most notable examples are the ‘new man’, the subject of Sean Nixon’s Hard Looks: Masculinities, Spectatorship and Contemporary Consumption (1996), the ‘new lad’ (Benwell, 2002) and more recently still the ‘metrosexual’, who Matthew Hall interrogates in Metrosexual Masculinities (2015).6 These models have already been joined by (and perhaps supplanted by) further media-generated soubriquets that have yet to attract the attention of scholars (but no doubt will), such as the ‘lumbersexual’,7 a figure whose iconography draws on traditional hyper-macho signifiers including beards, tattoos and plaid shirts (ironically and largely unintentionally referencing the gay macho look of the mid-1970s), and the rather more heightened and aggressively sexual version of the metrosexual, the so-called ‘spornosexual’ (the term here is a conjunction of sport and porn), whose developed muscular body and highly groomed appearance speak unambiguously of an overt and assertive sexual desirability.8 These proliferating contemporary masculinities might perhaps simply indicate an increasingly rapid pace of cultural and social change, or the rapacious demands of the modern media for constant novelty, but they certainly indicate a ramping up of the stakes regarding what can easily (and legibly) be ascribed as the constituent features of modern masculinities, not least because the term ‘sexual’ is so insistently a component of these portmanteau words and the attendant sexualised ways in which these masculinities are written about and received.

Gay and ‘Postgay’

Additionally there is evidence to suggest that the supposed fixity of specific masculine identities has become increasingly destabilised in recent times. Eric Anderson in Inclusive Masculinity (2009), for instance, makes a very useful disti...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author Bio

- Endorsement

- Series Information

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Editors’ Foreword

- Introduction: Coming to Terms (Again)

- Part I Contexts and Frameworks

- Part II Models, Patterns and Themes

- Notes

- Bibliography