![]()

CHAPTER 1

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

In this book, I analyse how Kurdish national, religious and economic elite blocs – the main three blocs – cooperate to establish a consensus on a common purpose: a Kurdish political region. I problematise the capacity of these blocs to produce a common cognitive frame, shared interests and accepted rules to establish a political region in Turkey. In other words, I ask whether three Kurdish blocs can found a political region in the historically existing Kurdish cultural region in Turkey. Therefore, the conflicts, negotiations, cooperation and consensuses of these blocs are the main subjects of this book.

As the actors and issues are historical and social constructs, the micro and macro sociological approaches must be articulated to analyse the construction process of a social phenomenon. The microsociology interrogates the interaction of the actors, their ideas, interests and institutions, while the macrosociology centres on the system of action of actors; in other words, the structured context that privileges some actors and interests while demobilising others.1 Therefore, in order to understand diverse Kurdish issues and the current conflicts, as well as the cooperation and negotiation of different Kurdish groups, we need to look at two interrelated levels. The first is the interaction of diverse actors who have complementary or controversial ideas, interests and institutions. The second is the system of action of the actors, who are embedded in a historically constructed context. This context is being continuously restructured and reshaped by the macro dynamic functioning as both constraints and resources for the Kurdish groups.

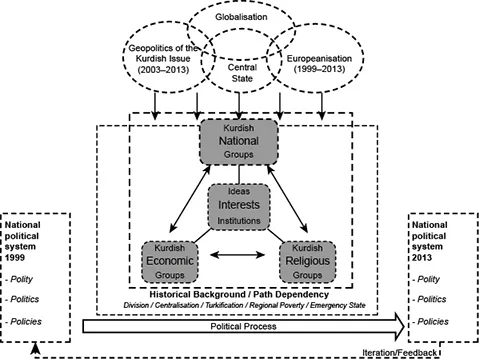

Given the fact that the present situation is framed and limited by formal and informal institutions,2 I add the historically constructed context of different Kurdish issues to the theoretical framework in which three Kurdish blocs exist and interact. In addition to the history, there are basically four main constraints/resources which influence different Kurdish actors, in different ways, at ideas, interests and institutions levels: the central state is unquestionably the first of these, as it interferes with the interaction of the Kurdish groups due to its infrastructural and despotic powers.3 Given the fact that the Kurdish issue is a transnational and international problem, the geopolitical dynamic must be taken into consideration as a second significant constraint/resource. The third aspect is the Europeanisation process of Turkey. Lastly, I must note the globalisation process, which has had multiple effects on most of the actors and processes involved, including the central state, the geopolitics of the Kurdish issue, and Europeanisation.

The general theoretical framework of the research is presented in Figure 1.1. The history, the central state, the geopolitics of the Kurdish issue, the Europeanisation process and globalisation function both as constraints and resources in a different manner for asymmetrically structured Kurdish groups situated in the landscape of power. They mobilise these dynamics to construct and reconstruct their ideas, interests and institutions. It is also theoretically important to note that each constraint/resource has had an effect on each Kurdish group over different time periods. The actors, the historically constructed context, four constraints, temporality of the research, the 3-Is model and the main theses are discussed in a more detailed way in the next sections.

Figure 1.1 Theoretical model for interaction of nation, religion and class in the Kurdish region of Turkey.

Three Kurdish Blocs

I classify the main Kurdish groups in the Kurdish region within basic blocs: the national bloc, the religious bloc and the economic elite bloc. It is crucial to emphasise that I use the national, economic and religious concepts as ideal types in the Weberian sense4 to analyse the ongoing collective action in the Kurdish region. In reality, one cannot make a clear distinction among the collective identities, i.e. among the economic, religious and national ones.

The Kurdish national bloc

For the purposes of this book, the Kurdish national bloc comprises the secular groups that have identified the Kurdish national identity as a principal element in constructing and resolving the Kurdish issue. The bloc is composed of secular Kurdish political groups, of which the BDP–DTK5/PKK–KCK is considered the leader, representing a wide socio-political mobilisation in economic, social, political and cultural domains. The Kurdish national bloc contains two other pro-Kurdish parties – KADEP and HAK-PAR – and other secular political groups such as the newly founded pro-Kurdish party ÖSP, and TEV-KURD.

These groups advocate collective cultural rights for the Kurds, such as the ability to receive education in their Kurdish mother tongue and the availability of public services in their native language (or in both Kurdish and Turkish), as well as a politico-administrative status for the Kurds. It is crucial to underline that each Kurdish national group defines this politico-administrative status differently. It is used for diverse models such as local self-governance, regional administration, federalism and the like. They also share a secular political view, which does not see religion as an essential element for constructing and framing the Kurdish issue, although the concept of secularism is perceived and used differently by each group. Additionally, most of the other Kurdish national groups including the leading BDP–DTK/PKK–KCK group have an orthodox socialist/Marxist legacy, which confines and obstructs their capacity to cooperate with Kurdish religious groups and the economic elite.

The Kurdish religious bloc

The Kurdish religious groups constitute the second bloc within the Kurdish scene. The adjective ‘religious’ is used for those who view and frame the Kurdish issue through the lens of religion. In this book, the term ‘religion’ implies Sunni-Islam and Alevism, whilst the phrase ‘Kurdish religious groups’ refers to Alevi and Sunni-Muslim Kurdish groups. For these groups, religious identity is more important than a Kurdish national identity. Therefore, the priority of the religious identity has important effects on their ideas, interests and institutions. This priority defines how these groups construct the Kurdish issue and take a position vis-à-vis other relevant actors, i.e. the central state, the Kurdish national groups, and the economic elite. Although they agree on the priority of the religious identity, there are significant differences among the Kurdish religious groups about different aspects of the Kurdish issue, such as socio-economic underdevelopment, individual/collective cultural rights and territorial sovereignty. In other words, they have different Kurdish issues.

It is important to underline that there exists a historical separation between Alevi and Sunni-Muslim people throughout Turkey in general and within Kurdish society in particular. The Alevi religious community including people from Turkish, Kurdish and Arab national groups constitutes the principal religious minority in Turkey. Alevis have been subjected to policies of neglect, denial and assimilation for centuries. In spite of significant discussions on Alevism in the public sphere and the mobilisation of Alevi groups at multiple levels for the last two decades, the Turkish state and Sunni-Muslim people have not yet officially recognised them as a religious minority.

The Kurdish economic elite bloc

The Kurdish economic elite bloc covers economic elites who are principally located in the Kurdish region, though some of them also engage in economic activity beyond the region within Turkey, as well as outside of the country altogether. The Kurdish economic elite has a relatively lower capacity than the other groups due to the long-standing socio-economic underdevelopment of the Kurdish region. There have been widespread inequalities in per capita income between the Kurdish region and the rest of Turkey for decades. In spite of decades of discussions on regional disparity, the latest research shows that the Kurdish area is still the most disadvantaged part of the country. Because of under-development of the region, the existence of a Kurdish bourgeoisie has always been a debated issue among the political actors.

The members of the economic elite have several different organisations to represent and advocate their interests in the Kurdish region. Chambers of commerce, chambers of craftsmen and artisans, industrialist and business associations are the main institutions where the local and regional economic elite are represented. At the political level, although the economic elite are more heterogeneous than the national and religious groups regarding the Kurdish issue, their economic dependence on the centre gives the central economic and political authorities an unquestionable power to dominate and confine them. However, after 1999 the local government experience of the leading Kurdish party changed the politico-administrative context in the main provinces of the Kurdish region. The centre–periphery relationship between the Kurdish economic elite and Ankara has become more complicated after Turkey's exclusive position against the Kurdish economic elite in the IKR and the rise of the leading Kurdish movement in the eastern part of the country as the local-regional power. In short, while increasing their national sensitivities, the Kurdish economic elite struggles to maintain a political balance between central and local regional powers.

Five Constraints and/or Resources of Collective Action

The three Kurdish blocs and their different visions on the Kurdish issue(s), which are embedded in a historically constructed context, have been confined within four main dynamics: the central state, the geopolitics of the Kurdish issue, Europeanisation and globalisation. All these historically constructed constraints are not isolated, static, solid, bounded and completed, but interrelated, dynamic, fluid, permeable and process-based. They have a direct effect on the Kurdish issue and relevant actors by framing and structuring their ideas, interests and institutions on the one hand and providing new resources to mobilise for the current power struggle on the other.

Historically constructed context

The interaction of the Kurdish blocs occurs in a historically constructed context. This context can be defined as a network of formal and informal institutions that have laid out rules and structured the ideas, interests and institutions of relevant actors. In order to understand the influence of the historically constructed context on the collective behaviours of actors, we can invoke theories of neo-institutionalism and, in particular, historical institutionalism which centres on how institutions affect the behaviour of individuals.6 According to theories of neo-institutionalism, ‘the institutional organisation of the polity or political economy’7 is the principal factor that structures collective behaviour and generates distinctive outcomes.8 Neo-institutionalists underline the strategic interaction of the actors. They argue that institutions provide actors to manage the uncertainty during the collective action, by providing information about the past, present and future behaviour of others, as well as enforcing mechanisms for agreements and penalties for defection. Institutions also provide diverse frames, filters and methods of interpretation, cognitive scripts, categories and models. In other words, they determine what we must do and what we can imagine. In short, the institutions not only provide strategically useful information, but also structure the identities, self-images and preferences of the actors.

P. A. Hall and R. C. R. Taylor, in their frequently cited work on three new institutionalisms in political science,9 highlight two characteristics of the historical institutionalism, which are of particular importance for this book. First, historical institutionalists focus on ways in which institutions structure asymmetrical relations of power, by distributing sources unevenly across social groups, so as to privilege some interests while demobilising others. Contrasting the assumption of freely-contracting individuals, they tend to stress how some groups lose while others win due to a world in which the institutions give some groups or interests unequal access to power.

Second, the historical institutionalism invites us to focus on path dependency.10 Rejecting the postulate that the same operative forces will generate the same results everywhere, historical institutionalists recognise the importance of the contextual features of a given situation inherited from the past and stress the production of ‘paths’ and ‘lock-in’ effects by eliminating other alternatives.11 We can argue that in a given time and space, the formal and informal institutions, as the most significant of these features, are both the historical constructs and producers of these distinctive trajectories or paths. Path dependency, that has also been defined as ‘the influence of past over the present’12 or ‘sensitive dependence on initial conditions’,13 underlines the continuity and entirety of the past and present. It also highlights the importance of the existing institutions that confine and form the adaption and production of new institutions by structuring actors' preferences, identities and self-images.

Although historical institutionalists emphasise the influence of the past over the present, they do not pay enough attention to the fact that the relation of the past and the present is not linear and one-directional, but rather cyclic and two-directional. P. Connerton's argument is well to the point:

[W]e may note that our experience of the present very largely depends upon our knowledge of the past. We experience our present world in a context, which is causally connected with past events and objects, and hence with reference to events and objects which we are not experiencing when we are experiencing the present. And we will experience our present differently in accordance with the different pasts to which we are able to connect that present. Hence the difficulty of extracting our past from our present: not simply because present factors tend to influence – some might want to say distort – our recollections of the past, but also because past factors tend to influence, or distort, our experience of the present. This process, it should be stressed, reaches into the most minute and everyday details of our lives.14

In this matter, the distinction between ‘history’ and ‘memory’ can be useful for understanding the dynamic relationship between the past and the present. P. Nora, in this frequently cited article, makes a clear distinction between the memory and the history:

Memory and history, far from being synonymous, appear now to be in fundamental opposition. Memory is life, borne by living societies founded in its name. It remains in permanent evolution, open to the dialectic of remembering ...