![]()

1 On Naval Heroes

To what purpose could a portion of our naval force be, at any time, but more especially in time of profound peace, more honourably or more usefully employed than in completing those details of geographical and hydrographical science of which the grand outlines have been boldly and broadly sketched by Cook, Vancouver and Flinders, and others of our countrymen?1

In 1818 the Arctic geography of North America, the existence of a navigable northwest passage, even the insularity of Greenland were problems yet resolved, blanks on the polar map. In John Barrow's Chronological History of Voyages into the Arctic Regions the coast of northern Siberia winds away for thousands of miles. In comparison there is nothing of the northern coastline of Canada save two widely separate points: points set down by Samuel Hearne and Alexander Mackenzie where each had explored a river to its junction with the polar sea.2 The incomplete map of the Arctic region cried out for refinement and completion, and these points beckoned out of the encompassing emptiness, inspiring imaginations, summoning men to further exploration. Over the course of the century in an unprecedented spate of treks, expeditions, disasters and triumphs, the secrets of this coastline would be unravelled, a passage in all its tortuous complexity revealed.

8. ‘A Tribute to the Memory of the late Vice Admiral Lord Viscount Nelson’, commemorative print after John Hopkins, 1 January 1806. History records his deeds, Fame crowns him with laurels, while Britannia mourns her loss.

The North Pole would remain hidden beyond ramparts of ice for the whole century, an elusive prize waiting to be won. As an introduction to polar and naval hagiography, and to the context of naval reform, this chapter examines the representation of explorers and naval officers in literature and art to consider multiple, and varying, definitions of heroism throughout the nineteenth century. The scientific challenge of the Arctic mostly came second to the romantic and imaginative potential of the voyages. This chapter also develops the new historiography of the heroic reputation, evaluating the ways that personalities have been constructed and embellished, both during and after their lifetimes. Nelson clearly looms large in this pantheon of service.

Navy and Nation

The arrival of peace brought massive disarmament, social unrest, and severe economic retrenchment to a war-weary nation. Whereas exploration as an activity has been traditionally translated as an expression of imperialist power, Arctic voyages in the immediate years after Waterloo took place at a time of fiscal restriction and national unease. At the height of the Napoleonic Wars in 1809 the British Navy was the most powerful in history and had swelled to proportions that would not be equalled for a century: 773 ships, 4,444 officers and some 140,000 sailors. By 1817 the figure had fallen to thirteen ships of the line and some 23,000 seamen. At the outbreak of the Crimean War, forty years later, the manpower was a meagre 45,000, and even in 1900 it had only risen to 112,000.3

9. The cartographic temptation of the unknown, the alluringly empty chart from John Barrow's Chronological History of Voyages into the Arctic Regions, 1818.

Whilst regular sailors were discharged relatively easily, officers were career men; they had political clout and they could not be dismissed so freely. In fact their numbers increased until the Navy, in 1818, had one officer for every four men. But ninety percent of these officers had nothing to do; of 1,151 officers on the lists in 1846 only 172 were in full employment. Exploration and survey can be regarded as a useful employment for a peacetime navy, a suitable outlet for the skills of trained officers. Taking the lead in renewing attentions to polar exploration, during the first sixty years of the nineteenth century no fewer than 190 Admiralty ships were employed on missions of discovery. Before John Franklin's last expedition in 1845 the Admiralty had been responsible for ten expeditions to ‘battle’ to find a northwest passage or to ‘lay siege’ to the North Pole.4

In an influential essay published anonymously in The Quarterly Review in 1817, John Barrow, Second Secretary to the Admiralty, spelt out his convictions for Arctic discovery. He warned that the Russians were ‘strongly impressed with the idea of an open passage around America’, declaring that ‘it would be mortifying if a naval power but of yesterday could complete a discovery in the nineteenth century, which was so happily commenced by Englishmen in the sixteenth’.5 Barrow grew impatient with those who thought the exploration of the Arctic to be a useless project, and for the whole of his life he remained convinced of the broad benefits of discovery voyages.6 But this is perhaps not enough to explain how the Admiralty was able to mobilise government and popular support for the ventures. Barrow submitted expedition proposals as ‘worthy of research … no less interesting to humanity than to the advancement of science and the probable extension of commerce … and the facility it offers of correcting the very defective geography of the Arctic regions in our western hemisphere’.7

With an unrivalled passion, Barrow envisaged the Navy as an untapped resource for the advance of geography and hydrography. He identified more abstract scientific problems that might be resolved with valuable information gleaned from high latitudes. That the aims of science and empire were complementary was recognised quickly by Barrow and under his direction the Admiralty succeeded in forming an alliance with the Royal Society. Throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth century ‘science’ and the Navy were unhappy bedfellows – institutionally and practically disparate – yet Barrow was able to bring the two together, offering a variety of justifications for exploration that would have appealed and resonated with different interest groups, whilst the alliance itself was consecrated by reforms to the Board of Longitude.

The Royal Society and the Admiralty would operate together under the banner of a ‘disinterested’ science, whilst at the same time the idea of exploration could also meet national and naval prestige concerns. Through the acceptance of this rationale, Barrow's Arctic exploration programme became a matter of national imperative and moral obligation. ‘If left to be performed by some other power’, he announced many times, ‘England by her neglect of it after having opened the East and West doors should be laughed at by all the world for having hesitated to cross the threshold’. The contradictions inherent in his vision of progress and discovery were sustained by social hierarchies and controlled by the Navy with the support of the Geographical Society of London, the Royal Society, the King and Parliament.

In a career devoted to lobbying and promoting exploration, Barrow cultivated the public image of explorers, endowing exploration with value, to counter the great many critics who questioned the usefulness of these voyages. Barrow's historiography of exploration, a personally constructed Arctic myth, predominated throughout the century. Evaluating the merits of polar voyages by 1845, unsurprisingly, Barrow remained committed to their benefits. Beyond the long list of scientific justifications, exploration's fundamental value lay in its instructive potential. He summarised his life's labours as a polar publicist: a career devoted to ‘the instruction of a class of readers in the record of achievements of their countrymen’, and to ‘popularise the fame of gallant and enduring men’.8 Moral achievement, perilous danger, and individual action were key components of this vision.

Deliberately cultivating a myth of piety, fortitude, and duty, Barrow invented a tradition of national enterprise that could be robust even through failure.9 Barrow's efforts drew praise from Francis Egerton, Lord Ellesmere, who saw in exploration the potential to vivify the public's impression of their Navy: ‘a more enviable position on the record of human achievement we can hardly conceive than that which will be enjoyed by the leaders of these various expeditions by sea and land … adorning our history with exhibitions of stern resolution coupled with the purest humanity’.10 Explorers took the stage as ‘heroes in a long and varied Saga of northern adventure’, prime examples raised for emulation for those within the service and those who could enjoy reading about their deeds, ‘for nothing is more remarkable than that wonderful pertinacity in enterprise which maritime pursuits have the power to generate’. His narrative imagining of naval engagement was a romanticised ideal, yet it was one that could be of benefit to everyone concerned, particularly so for the Navy. The post-war naval ‘crisis’ was not only one of size, but also one of identity.

A Century of Change

Interest in Arctic exploration may be justified in the context of Admiralty weakness. After the cessation of war with France, domestic interests soon marginalised the Navy, which proved painfully slow to adjust to a different, increasingly commercial, world and reassess its relevance to a post-war society that had fewer pressing martial preoccupations.11 For the Navy, as with the nation, it was an age of reform and technological revolution. In this context of change it is no surprise that heroic images, a construction of an imagined chivalrous past, found a receptive audience. Projected in an appealing light, polar exploration was an expedient national advertisement for the Navy, for its ongoing vitality and the spirit of its seamen, and the Admiralty seized its potential to generate positive publicity.

In the absence of any major crisis abroad the Navy was highly vulnerable to spending cutbacks and demands for retrenchment were insistent: more than twenty-five percent of all reports about the Navy appearing in The Times between 1815–25 related to calls for greater economy in the service to relieve the huge burden of national tax. Scores of ships were ‘laid up in ordinary’ and hundreds of officers sought active employment. As the imminent reduction in manpower threatened capability and its, up till now, die-cast reputation, the image of the explorer was press-ganged into service.

This period was a time of profound changes in the nation's Navy: witnessed in new uniforms, a ‘continuous service scheme’ which dispensed with impressments, the increased respectability of life at sea and the movement to humanise punishments, the restriction of grog, and, most important, far-reaching reforms of the Admiralty itself. But the naval changes that attracted most speculation and ridicule in the press, and in the increasingly popular journal Punch for example, were those of technology. However nostalgic the image of a naval supremacy secured ‘by glorious sail’ might seem – with the image of Nelson central to this imaginative makeup – it remained a key component of the service's collective consciousness during the long Victorian period despite the fact that ‘Nelson's Navy’ was soon but a distant memory.

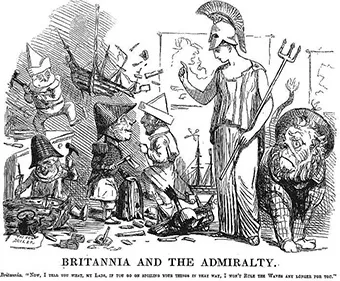

10. Satirising naval reform: ‘Britannia and the Admiralty’, Punch, 15 December 1849.

11. The Navy's changing face: ‘The “British Tar” of the Future’, Punch, 12 April 1862.

Change was heralded by the decline of the wooden ship-of-the-line, the advent of the ironclad, and the highly contested adoption of new methods of steam propulsion. The main lines along which the modern battleship evolved are now easily distinguishable: from sail to steam; from wood to iron; from guns mounted broadside to guns mounted in turrets. Yet it was not, of course, an effortless process and the public were frequently confused by the costs and the merits of this ‘progress’. And, unsurprisingly, all of these developments were chronicled and commented on in the pages of the metropolitan newspapers, journals like Punch and the rapidly expanding illustrated press.

Whilst there is no space here to expand more fully on the introduction of steam propulsion into the Victorian Fleet, suffice it to say, it was a trial of protracted contests and negotiations, technical difficulties, and, not least, considerable expense.12 Though the last battle between sailing ships was fought at Navarino in 1827, the last line-of-battle ship under sail was Sanspareil, laid down in 1851. The first to be designed as a steamship, instead of just having auxiliary engines installed, was Agamemnon of 1852. As late as 1847, John Barrow was ridiculing the idea ‘of a fleet of iron steam vessels, altogether useless, it would seem, as ships of war’.13

The first five iron frigates built in 1845 were found to be totally inadequate. Waves of concern about the combat readiness of the British Fleet swept Westminster. Newspapers and journals ran articles on parlous armoury and the inadequacy of domestic manpower. Uneasy relations with France were exacerbated by her adventurism in Morocco, political sabre-rattling, and the channel-crossing bellicosity of Parisian commentators. In January 1848 The Times and other papers printed what, under the circumstances, could only be called a ‘bombshell’: a letter from the Duke of Wellington to Sir John Burgoyne, the inspector-general of defences, expressing his concern over the nation's vulnerability to a continental invasion, as well as the unaddressed problems attending the Navy's slow conversion to steam. Reaction was divided: some shared the alarm whilst others were quick to mock the idea of an invasion.

The following year Rear Admiral Sir Charles Napier, commander of the Channel Fleet, wrote a series of letters on the steam fleet to The Times, questioning its size, combat effectiveness, and escalating costs. The Navy, he warned, was dangerously under the strength it had possessed at the conclusion of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815. The policy of breaking up oaken warships, ‘the wooden walls’ of England, and replacing them with untried iron ones or, alternatively, ‘modernising’ dilapidated old hulks by converting them into leaky new tubs was, according to Sir Charles, misguided – even suicidal.14

Journals echoed his concerns over Admiralty retrenchment with satirical broadsides. ‘The public is aware that there is something very rotten in the state of our Navy in gen...