![]()

1

Culture and society in Britain: Historians and other intellectuals in the 1950s

The calendar and historical ‘ages’ or ‘periods’ only rarely coincide. And so we have on offer, for example, a ‘long eighteenth century’ (beginning in 1688) and a ‘short twentieth century’ (ending in 1989). One account of Britain in the 1960s starts, for several good reasons, in 1956, whereas from another standpoint the 1950s drew to a close in 1963,

Between the end of the ‘Chatterley’ ban

And the Beatles’ first LP.1

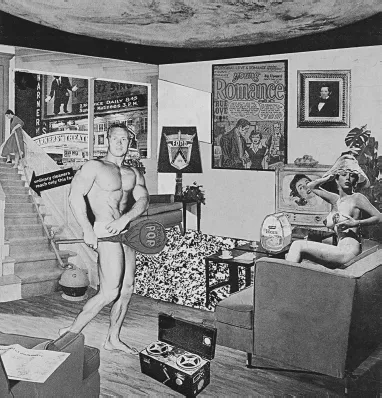

Did, then, a distinctive ‘Fifties’ ever exist? Many who experienced them directly were in no doubt, held clear views on the period’s political contours and cultural characteristics, and were all too happy saying goodbye to all that. In the summer of 1959 the Marxist historian and polemicist, E.P. Thompson, observed that ‘we have been living through the decade of the Great Apathy’ and, the following year, edited a collection of essays entitled Out of Apathy. Fellow New Left luminary Perry Anderson later recalled an ‘anguished, parched decade’;2 a judgement passed in hindsight, it is nonetheless corroborated over and over again by voices from what J.B. Priestley called in 1953 ‘the wilderness’. From his weekly column in the New Statesman Priestley offered his thoughts on the dullness of politics, the exhaustion of economics, and the general boredom of people who ‘spend their evenings watching idiotic parlour games on TV’, and who ‘are aware, if only obscurely, of this central vacuum’.3 Was it really all so grim? Expressions of political and cultural frustration tended to emanate from the left, and Norman MacKenzie (also of the New Statesman) complained of ‘a paralysis of socialist thinking’, albeit in the introduction to a volume of polemic, Conviction (1958), which in itself signalled fresh energies in radical quarters.4 Of course an alternative version of the later 1950s presented itself: a brash new world of consumer goods and advertising, commercial television and espresso bars, captured and eviscerated so brilliantly by Richard Hamilton’s seminal ‘pop art’ collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? (1956) and recorded for posterity in Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s claim that most of the British people had ‘never had it so good’. And ‘in real terms consumer expenditure rose by 45 per cent between 1952 and 1964.’5 Had, then, the heralds of a ‘New Elizabethan Age’ at the time of the coronation been right after all?

Coronation

On 2 June 1953, the historian of ideas, Isaiah Berlin, watched from an upper-floor window of the Daily Telegraph offices in Piccadilly as the coronation procession of Queen Elizabeth II passed by on its way to Westminster Abbey. ‘Nobody would quite have thought,’ he wrote a few days after, ‘that this sober, unimaginative and essentially prosy country could rise to such a pitch of national excitement over this dark mystical Byzantine ceremony, which seems in a sense so out of keeping with the reticent, moderate, good taste-seeking undemonstrative English character.’6 If the quasi-religious rhetoric now sounds overblown, it is in fact quite mild by the standards of the day. The periodical Time and Tide carried an article on the Royal Family – ‘a symbol of inestimable importance in the life of the nation and commonwealth’ – entitled, simply, ‘The Cynosure’ (defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘something that attracts attention by its brilliancy or beauty; a centre of attraction, interest, or admiration’). From this the reader learns that the ‘the monarch, the person in whom it is embodied and the family which surrounds that person’ is nothing less than a ‘miracle for which we cannot be sufficiently thankful’. Meanwhile, over at the Spectator they were imagining that ‘there might in some sense come a second Elizabethan greatness’. Not even the inevitable downpour of rain could dampen the palpable sense of national renewal, a sense boosted by Edmund Hillary’s timely ‘conquest’ of Mount Everest, news of which reached London on the morning of 2 June.7

Reverential effusions were, in the circumstances, to be expected: a people with a strong sense of ‘tradition’, an institution, monarchy, with a flair for ornate, spectacular, ceremonial, and an excuse for national celebration in a time of drab, still-lingering, postwar austerity, combined to whip up ‘coronation fever’. Kingsley Martin, editor of the New Statesman and, in 1937, author of The Magic of Monarchy, took a rather relaxed view of the festivities, noting that

in 1953, newspapers find that the public appetite for monarchy is unlimited […] the public is not under any illusions that we can be saved by magic or that the coronation is more than a royal carnival. In that spirit, without silliness or solemnity, we can enjoy ourselves.8

That is not, however, the spirit in which the sociologist, Edward Shils, approached the matter, as he pontificated solemnly on ‘national communion’ and ‘moral sentiments […] at a high pitch of seriousness’.9 But while this less-than-clinical analysis by a seemingly overwrought American Anglophile has little or no value as ‘sociology’, the assumptions and attitudes which it hides and displays are of interest to the historian of British intellectuals in the 1950s, a subject on which Shils himself wrote.10

First there is the issue of ideology, which, Shils announced, had come to an end in the 1950s – come to an end, that is, in the ‘free world’. Turning their hand to political theory the editors of the British Medical Journal believed that just as the Crown transcends politics, so British politics are above ideology. ‘In these days,’ they announced, ‘when various “ideologies” spread their ugly mantles over bewildered populations the Crown shields us within its beneficent circle, securing those who look up to it against the disintegrating forces at work in so many parts of the world.’11 It did not occur to the medics or to Shils either that royalism, including the constitutional variety, is itself an ideology, as if eighteenth-century Jacobites, say, or nineteenth-century French monarchists, had been inspired by a sort of no-nonsense pragmatism.

Then there is the matter of royalist sentiment shared by intellectuals, particularly historians. Herbert Butterfield, a nonconformist in religion, and a political contrarian, nonetheless considered the history and evolution of monarchy a function of the English political genius:

It is typical of the English that, retaining what was a good in the past, but reconstructing it – reconstructing the past itself if necessary – they have clung to the monarchy, and have maintained it down to the present, while changing its import and robbing it of the power to do harm. It is typical of them that from their 17th-century revolution itself and from the very experiment of an interregnum, they learned that there was still a subtle utility in kingship and they determined to reconstitute their traditions again, lest they should throw away the good with the bad. In all this there is something more profound than a mere sentimental unwillingness to part with a piece of ancient pageantry – a mere disinclination to sacrifice the ornament of a royal court. Here we have a token of the alliance of Englishmen with their history which has prevented the uprooting of things that have been organic to the development of the country; which has enriched our institutions with echoes and undertones; and which has proved – against the presumption and recklessness of blind revolutionary overthrows – the happier form of co-operation with Providence.12

Butterfield’s ‘old enemy’13 Lewis Namier, by reputation the foremost historian at the time, could not (according to J.H. Plumb) conduct a conversation for more than ten minutes without one ‘realizing the depth and strength of his conservatism or his veneration for monarchy, aristocracy and tradition’.14 In his 1952 Romanes Lecture Namier endorsed Churchill’s view of constitutional monarchy as ‘of all the institutions which have grown up among us over the centuries […] the most deeply founded and dearly cherished’, adding his own opinion that it is ‘anchored both in the thought and affection of the nation’.15 The Crown symbolized and cemented national unity and, he believed, together with a civil service which stood outside party politics, a Crown which stood above them guaranteed political stability and continuity. It may be that Plumb (himself a friend of Princess Margaret) is an unreliable witness on the subject of Namier – by whom he felt slighted at the beginning of his career, and in whose shadow he long toiled. Having been Plumb’s ally during the 1950s, in 1964 – four years after the great man’s death – he wrote that ‘it is a sad comment on the state of historical writing in England that his reputation should have been so high’.16 It may also be the case that Plumb did not always let facts get in the way of a good story, but, because they are good, some stories bear repeating. At a meeting which he attended in the early 1950s with Namier, Sir John Neale and others at Trinity College, Cambridge, to discuss the nascent History of Parliament project, ‘one famous quarrel lasted a long afternoon’

and was about capitalization – should it be Duke of Bedford or duke of Bedford, Queen of England or queen of England. Neale argued at length for the lower case; with mounting rage Namier would not have it, his eyes glowed, his voice rasped; Neale pressed and Stenton slept. At last, after an hour or two spent on probable savings in costs, difficulties for proof-readers and other red herrings, Namier growled in his strong Polish-English – ‘I will not have my Queen with a small “q”. You can show your lack of respect if you like. I will not. The volumes must differ.’17

There is no question on which side of that debate Namier’s good friend John Wheeler-Bennett would have stood. The official biographer of George VI, Wheeler-Bennett remarked that royal biography, like matrimony, was an enterprise ‘not to be entered into inadvisedly or lightly; but reverently, discreetly, advisedly, soberly and in fear of God’.18 John Brooke, Namier’s closest collaborator, and afterwards keeper of his flame, went on to write the official biography of George III.19

Deference to monarchy is an expression of English nationalism. Namier, by origin a Polish Jew, shed no tears over the fall of the Tsar, the Emperor or the Kaiser. Berlin, by origin a Latvian Jew, pondered what the coronation said about the ‘English’, not the British, character. Butterfield saw the providential survival of monarchy as evidence of ‘the alliance of Englishmen with their history’. Royalism is also intrinsically conservative. Namier described himself as a ‘Tory Radical’. Yet many on the left, like Kingsley Martin, while eschewing Shilsian pieties and excoriating the ‘Establishment’, on the ‘apex’ of which rested the Crown,20 conceded that hereditary monarchy served some useful purpose. In the 1950s Isaiah – soon to be Sir Isaiah – Berlin even considered himself, with his signature and verbose equivocation, a man of the left who is ‘on the extreme right-wing edge of the left-wing movement, both philosophically and politically, and rightly regarded with suspicion by the orthodox members of the left-wing movement’.21 Republicans were presumed not to exist and must indeed have been thin on the ground. However, when Berlin accepted his knighthood (for, it was said, ‘services to conversation’)22 he received a rebuke from his Oxford colleague, the labour historian G.D.H. Cole, ‘for having “sold out” to some vague establishment’, and for visiting ‘the Palace inhabited by “That Woman”’.23

Throughout the 1950s the leftist literary theorist Raymond Williams made notes on what would eventually become his Keywords: ‘an inquiry into a vocabulary: a shared body of words and meanings in our most general discussions, in English, of the practices and institutions which we group as culture and society’.24 Included in his compilation are ‘communism’, ‘democracy’, ‘imperialism’, ‘liberal’, ‘nationalist’ and ‘radical’; absent are ‘republican’ and ‘monarchy’. Perhaps the latter institution was so tightly stitched into the fabric of culture and society that Williams’ searching critical eye scarcely noticed it?

Giddy talk of a second Elizabethan age soon fizzled out and in the years ahead the monarchy even came under public attack, most trenchantly as ‘a ridiculous anachronism’.25 But back in 1953 the coronation – for all its flummery and transience – did affirm ‘traditional’ British values: patriotic, deferential, conformist. Thompson’s age of apathy, Anderson’s ‘parched decade’ and Priestley’s ‘vacuum’ did, after all, register three consecutive Conservative Party general election victories in 1951, 1955 and 1959, while throughout this period Lord Beaverbrook’s right-wing, middle-brow Daily Express continued to enjoy the widest circulation of any British newspaper. Neither intellectual climate nor institutional cu...