- 392 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This title is presented with a new foreword by Istvan Deak. The battle of Budapest in the bleak winter of 1944-45 was one of the longest and bloodiest city sieges of World War II. From the appearance of the first Soviet tanks on the outskirts of the capital to the capture of Buda Castle, 102 days elapsed. In terms of human trauma, it comes second only to Stalingrad, comparisons to which were even being made by soldiers, both German and Soviet, fighting at the time. This definitive history covers their experiences, and those of the 800, 000 non-combatants around whom the battle raged.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Battle for Budapest by Krisztián Ungváry, Ladislaus Lob in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Prelude

1

The general situation in the Carpathian Basin, autumn 1944

The German front in eastern Romania collapsed after the arrest of Prime Minister Ion Antonescu and the severance of diplomatic relations between Romania and the German Reich on 23 August 1944. Following the destruction of large segments of the German Army Group South, units of the 2nd Ukrainian Front encountered practically no resistance to their advance through Romania, and arrived at Hungary’s Transylvanian border on 25 August. Early in October they also reached the border in the south of the Great Hungarian Plain. On 6 October they began their general offensive with the aim of encircling – together with the 4th Ukrainian Front from the Carpathians – the German and Hungarian troops (roughly 200,000) in Transylvania. Table 1 indicates the balance of German and Soviet forces in Hungary at the beginning of October 1944 (see ‘Tables’ section at the end of the book).

Along the 160-kilometre front between Makó and Nagyvárad, two armoured and two mechanised Soviet corps, with 627 tanks and 22 cavalry and infantry divisions, set out north to meet the Hungarian 3rd Army with its 70 tanks and 8 divisions. The Hungarian front, lacking anti-tank defences, was soon torn to shreds, and the Soviet troops were ordered to advance towards Debrecen. In the meantime the Germans had also concentrated forces in the region: Operation Zigeunerbaron (Gipsy Baron) was intended to destroy the 2nd Ukrainian Front’s units on the Great Hungarian Plain and then, turning south and east, seize the passes in the Carpathians to form an easily defensible battle line. The tank battle of Debrecen took place between 10 and 14 October. Table 2 shows the sizes of the respective forces before the battle.

Although the Soviet units succeeded in occupying Debrecen on 20 October 1944, they were unable to fulfil their aim of encircling the German 8th Army and the Hungarian 1st and 2nd Armies stationed in Transylvania and the Carpathians. In addition, the 4th Ukrainian Front under Major-General Ivan Yefremovich Petrov, which should have closed the circle from the north, had made hardly any headway. Thus the German Army Group South succeeded in extricating its troops. After Regent Miklós Horthy’s failed attempt of 15 October to break away from Germany and agree a separate peace with the Soviets, the panzer units that had so far been tied down in the border area added their strength to the German front. By 20 October, the Germans had lost only 133 tanks, while the losses of the Soviets amounted to 500 – more than 70 per cent of their strength.1 By the end of October, the German panzer divisions had encircled General Issa Aleksandrevich Pliev’s mechanised cavalry units in the Nyíregyháza region, and the Soviet troops were only able to break out with heavy losses.

Between Baja in the south and Szolnok in the east, only seven exhausted divisions of the Hungarian 3rd Army and 20 tanks of the German 24th Panzer Division were holding their positions against the Soviet 46th Army, as the bulk of the German armoured forces had been redeployed to the tank battle of Debrecen. The distance between Budapest and the Soviet lines was only about 100 kilometres. Nevertheless, a Soviet attack was risky, because the German tanks could easily be regrouped to defend the city, while the Soviets no longer had enough armoured vehicles to carry out a successful offensive.

While the Soviet occupation of Hungary was continuing in the region beyond the Tisza river and in the southern part of the Great Hungarian Plain, in Budapest and the western parts of the country the Arrow Cross government was establishing its reign of terror.

The Arrow Cross Party had come into being during the second half of the 1930s, through the merger of several far-right groupings. Its emergence was facilitated by widespread disillusionment with the communist republic of 1919, the surviving feudal structures and the anti-Semitic traditions of Hungarian society. The party was led by Ferenc Szálasi, a suspended general-staff major. In the 1938 elections it had proved extremely popular in working-class districts, obtaining about 20 per cent of votes. Its programme promised land reform, social reforms for workers and peasants, the complete elimination of Jewish influence and the subsequent deportation of all Jews from Hungary, and the creation under Hungarian leadership of a federal state called the Hungarist Carpathian-Danubian Great Fatherland, which was to comprise Hungary, Slovakia, Vojvodina, Burgenland, Croatia, Dalmatia, Ruthenia, Transylvania and Bosnia. From the National Socialists it had adopted the Führer and Lebensraum principles.

Although in reality the fate of Budapest was determined by German military policy, according to the Arrow Cross Party the Hungarian people were now obliged to fight against the violence, looting and deportation to Siberia that the approaching Soviet army would bring with it. The persecuted Jews saw the advancing Soviet troops as their saviours. The rest of the population, however, had gloomy forebodings. The relative calm presented by Budapest on the surface was frequently disturbed by Jews being marched to the ghettos or deported to German camps, columns of refugees leaving their homes to trek west, and reports of evacuation orders arriving from the Great Hungarian Plain. ‘We must now be prepared to become a city under siege from one day to the next’, the linguist Miklós Kovalovszky notes in his diary, after describing a scene observed in the suburb of Kispest:

The old woman is speaking in tears about the evacuation of Kecskemét. They were able to bring a few pieces of clothing and some food with them, but there wasn’t enough time to get the three pigs from the farm. The whole town has become a poorhouse; and what if they have to move on from here as well?2

2

‘They are coming!’ – the first Soviet offensive against Budapest

Plans and preparations

Immediately after the tank battle of Debrecen, Josef Stalin ordered the 2nd Ukrainian Front to take Budapest and continue its advance towards Vienna. With the eventual division of conquered territories between the Soviet Union and the Western Allies in mind, he wanted to secure his supremacy over central Europe as early as possible. During the Moscow negotiations of 8–18 October, Winston Churchill had mentioned his plan to move the British and US forces to the Carpathian Basin. This induced Stalin to act promptly. His decision was influenced through a misleading report presented in late October by Colonel-General Lev Zakharovich Mehlis, the political representative of the 4th Ukrainian Front’s commander:

The units of the Hungarian 1st Army facing our front are disintegrating and demoralised. Day by day our troops capture 1,000-2,000 men, sometimes even more . . . The enemy soldiers are wandering in small groups in the forests, some armed, others without arms, many in civilian clothes.3

Stalin asked his general staff whether there was any real chance of taking Budapest. The memoirs of Colonel-General Sergei Shtemenko, the first deputy of the Red Army’s chief of staff, relate:

Without suspecting anything, we replied that it would be most practical to attack from the well-established bridgehead in the Great Hungarian Plain which had been captured by the left wing of the 2nd Ukrainian Front. This would not involve crossing the river, and the enemy had fewer troops here than elsewhere.4

Stalin ordered an immediate attack, ignoring the reservations of General Aleksei Innokentevich Antonov, chief of the Red Army’s general staff, who explained that Mehlis’s reports applied only to the Hungarian 1st Army and not to the situation as a whole.5 On 28 October at 10pm the following telephone conversation took place between Stalin and Rodion Malinovsky, the commander of the 2nd Ukrainian Front:

S: Budapest . . . must be taken as soon as possible, to be more precise, in the next few days. This is absolutely essential. Can you do it?

M: The job can be done within five days, when the 4th Mechanised Guard Corps arrives to join the 46th Army . . .

S: The supreme command can’t give you five days. You must understand that for political reasons we have to take Budapest as quickly as possible6 . . . You must start the attack on Budapest without delay.

M: If you give me five days I will take Budapest in another five days. If we start the offensive right now, the 46th Army – lacking sufficient forces – won’t be able to bring it to a speedy conclusion and will inevitably be bogged down in lengthy battles on the access roads to the Hungarian capital. In other words, it won’t be able to take Budapest.

S: There’s no point in being so stubborn. You obviously don’t understand the political necessity of an immediate strike against Budapest.

M: I am fully aware of the political importance of the capture of Budapest, and that is why I am asking for five days.

S: I expressly order you to begin the offensive against Budapest tomorrow!

Stalin then put down the receiver without saying another word.7

Experts disagree about whether Stalin made the right decision. When the order to attack was given, the 23rd Rifle Corps, which had been promised as a reinforcement, was still on its way. The 2nd Mechanised Guard Corps did not join Malinovsky, who had no other armoured units, until the next day, and the 4th Ukrainian Front, which should have taken part in the encirclement of Budapest, was unable to reach the Great Hungarian Plain.

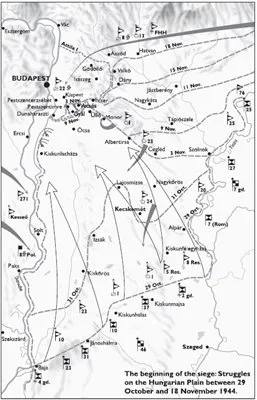

The beginning of the siege: Struggles on the Hungarian Plain between 29 October and 18 November 1944.

The German army command, recognising the Soviet threat, had already begun to redeploy its troops on 26 October.8 By 1 November, the 23rd and 24th Armoured Divisions had been moved to the Kecskemét region, and the redeployment of the 13th Panzer Division, the Feldherrnhalle Panzergrenadier Division and the Florian Geyer 8th SS Cavalry Division had also begun. With these forces, the commander of the German Army Group South, Colonel-General Hans Friessner, was planning to regain the Great Hungarian Plain and establish a solid defensive position along the Tisza.

The offensive, introduced by a brief artillery barrage, began at the appointed time south of Kecskemét with a northbound attack of the Soviet 37th Rifle Corps and the 2nd Mechanised Corps. The Soviet tanks soon broke through the Hungarian defences over a 25-kilometre stretch. The onslaught continued during the night, despite an unsuccessful counterattack by the 24th Panzer Division, but faltered on 30 October when German and Hungarian troops – particularly anti-aircraft artillery – destroyed 20 tanks in the neighbourhood of Kecskemét alone. On the same day the Soviet 7th Guard Army set out to cross the Tisza, but gained ground slowly. On 31 October the Soviet troops captured Kecskemét, and on 1 November, Malinovsky gave orders for the 4th Mechanised Guard Corps and the 23rd Rifle Corps to take Budapest within three days, before the Germans could regroup.9 The armoured vehicles and riflemen transported by trucks and horse carts were to carry out a surprise crossing of the Danube and encircle Budapest from the south. At the same time the 2nd Mechanised Guard Corps was to overrun the city from the east. As the majority of Soviet troops was still 40–50 kilometres from Pest and there were no bridgeheads on the Buda side, the plan in practice presupposed that it was possible to ‘walk’ into the capital without further ado.

A general of Malinovsky’s calibre must have known that these objectives were unrealistic. One can only assume that once Stalin had overruled his objections, he had no choice but to obey. Subsequent events bear witness to the remaining strength of the Hungarian (not to mention the German) army, in what was to be, for Hungary, the last and most devastating phase of the war. While the awareness of approaching defeat and the terror perpetrated by the Arrow Cross government increasingly fuelled the people’s desire for an end to the ordeal, the army still possessed substantial energy reserves. This was one of the reasons why the siege of Budapest was to prove so long and bloody. In the initial stages the Hungarian units on the Danube and their German reinforcements presented a weighty obstacle to the premature Soviet attack. In any case, an early breakthrough by the Soviets would have been almost impossible because they lacked the necessary resources....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Author biography

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Illustrations

- Maps

- Map Legend

- Foreword by István Deák

- Preface

- Introduction: Hungary and the Second World War

- I Prelude

- II The Encirclement

- III The Siege, 26 December 1944–11 February 1945

- IV Relief Attempts

- V The Break-out

- VI The Siege and the Population

- 7 The Soviet crimes

- VII Epilogue

- Tables

- Bibliography

- Photographic Acknowledgements