![]()

PART I

ORIGINS

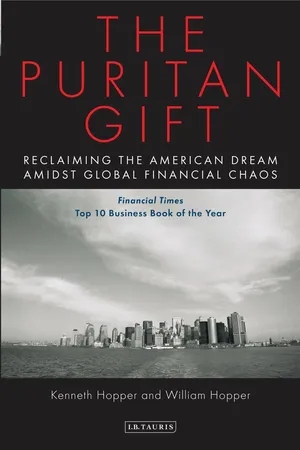

1: Round Stone Barn (1780). See here.

2: A locomotive called Brother Jonathan, originally known as The Experiment (1832).1 See here.

3: SS Brother Jonathan (1865). See also here.

![]()

1

The Puritan Origins of American Managerial Culture1

Traditional American society, particularly but not only in New England, possessed a quartet of characteristics, intimately bound together, that reached back to the earliest days of the Bay Colony of Massachusetts and still colors the outlook of most citizens of the United States. These were: a conviction that the purpose of life, however vaguely conceived, was to establish the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth; an aptitude for the exercise of mechanical skills; a moral outlook that subordinated the interests of the individual to the group; and an ability to assemble, galvanize and marshal financial, material and human resources to a single purpose and on a massive, or a lesser, scale. All of these elements were associated with the colony’s Puritan origins.

The Puritan movement originated in the British Isles around 1560, when dissident members of the Church of England, still the mother church of the Anglican Communion today, attempted to ‘purify’ it by removing all trace of its Roman Catholic past. All four of the characteristics described above were already present among the founders, the Bay Colony being simply an extension of an important part of English society. Thus, for a brief period, some people on both sides of the Atlantic sought to create their ideal society on earth as a material as well as a spiritual realm – a society to be constructed by dint of hard, physical work and the application of intelligence. From the outset, there was an emphasis on the importance of both mechanical and managerial skills, as well as a willingness on the part of individuals to subordinate their personal interests to a concept of a greater good. The Puritan migration to America of the 1630s – of which much more in Chapter 2 – was a masterpiece of organization, from which many important lessons can be learned today.

The famous English essayist and jurist, Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626), was both the philosopher of Puritanism and the prophet, at least by implication, of the Industrial Revolution to come. Bacon had studied at Cambridge University, which (unlike its more conservative rival, Oxford) was a hotbed of religious dissent. A pious Christian, he told us that: ‘A little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism, but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion’.2 He also wrote, eloquently, about the importance of the ‘mechanical arts’ – as he called them – which, ‘founded on nature and the light of experience . . . are continually thriving and growing, as having in them a breath of life, at the first rude, then convenient, afterwards adorned, and at all times advancing’.3 For him, there were three things that made a nation great: ‘a fertile soil, busy workshops [and] easy conveyance for men and goods from place to place’ – all being dependent on tools devised by man and the third pointing to an increasing mastery of the technology of travel, without which the Puritan migration could not have succeeded.

Bacon particularly admired the ‘recent’ inventions of printing, gunpowder and the compass (the ‘mariner’s needle’):

For these three have changed the whole face and state of things throughout the world; the first in literature, the second in warfare, the third in navigation; whence have followed innumerable changes, insomuch that no empire, no sect, no star seems to have exerted greater power and influence in human affairs than these mechanical discoveries.4

Joint-stock companies would pay a key role in the future industrialization of both Old and New England. Bacon was a pioneer in their development in his capacity as one of the seven hundred shareholders in the Virginia Company, which made the first permanent English settlement in North American in 1607. Like many future capitalists, he lost money on this venture.5 The Baconian view of life and work was imported by the Puritans into New England, where it took deeper root than in Old England and would shape not just the economy but the very nature and structure of society. In 1865, the French author, Jules Verne, would remark in his novel From the Earth to the Moon that ‘Yankees, who are the world’s finest mechanics, are engineers in the same way as Italians are musicians and Germans are metaphysicians – they were born that way’.6 With uncanny insight, Verne foresaw the moon shot of 1969, when human beings first set foot on the earth’s largest satellite, the ultimate achievement (in both senses of that term) of America’s great mechanic culture.

The desire to create the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth was famously encapsulated in a sermon delivered by John Winthrop, founding governor of the colony, to his fellow migrants in 1630 apparently before they set sail. New England was to be ‘as a Citty on a Hill’, a phrase he borrowed from the gospel of St. Matthew. As such, it was to be a model for succeeding American ‘plantations’ – the name then often given to colonies – so that men would say that the Lord had made them ‘like that of New England’.

In 1835, the French writer, Alexis de Tocqueville, in Democracy in America, would describe the civilization of New England as ‘a beacon lit upon mountain tops which, after warming all in its vicinity, casts a glow over the distant horizon’, permeating the entire Union.7 This characteristic would be partly secularized by the 1850s into a belief in ‘manifest destiny’, leading to the famous call to the nation’s male youth to ‘go West and grow up with the country’, attributed to Horace Greeley, founder and first editor of the New York Tribune. In its original form, it finds a persisting expression in the beliefs and practices of certain Protestant sects, which believe that Christ will return again and even make his appearance in America.

More generally, it expresses itself in a spirit of unyielding optimism about the future of society – which the citizens of other countries do not share – coupled with a conviction that problems exist to be solved. One of its purest exemplars was Benjamin Franklin, of whom Stacy Schiff has said that he ‘truly believed it was always morning in America’. (According to Schiff, Franklin also offered us the best one-line definition of America: ‘the New World judges a man not by who he is but by what he can do’.)8 In much the same spirit, Thomas Jefferson cunningly converted John Locke’s ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of estate [property]’ into ‘life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness’. More recently, this outlook has found a popular embodiment in the cartoon figure, Superman, who believes in ‘Truth, Justice and the American Way’. Although born on the planet Krypton, Superman grew up in Smallville, USA and, therefore doubles up as an ordinary American as well as a heroic, indeed godlike, figure.9

There is more than a hint of Superman in the personalities and outlook of Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the two roller-skating, flower-power-inspired founders of the computer science company, Google Inc., which now dominates the world of communications. Their motto is, ‘Don’t be evil’. We have been told that they are motivated by ‘puritanical fanaticism’ and a desire to change the world, making it a better place’; a visitor to their head office is reported to have said that he felt he was in the ‘company of missionaries’. Another observer says that ‘Google is a religion posing as a company’.10 What will the world resemble if they succeed in transforming it? No-one knows – not even they.

A willingness to become involved in mechanical tasks and to get one’s hands dirty distinguished American society from older and more stratified nations in Europe from the outset. This was not just a matter of indentured servants and the artisan class. An anonymous source tells us that, by the time they made landfall, the settlers from the advance party had become demoralized. However, ‘Now so soon as Mr Winthrop was landed, perceiving what misery was like to ensewe through theire Idleness, he presently fell to worke with his own hands & thereby soe encouradged the rest that there was not an idle person in the whole plantation’. When not involved in governing, he would be observed ‘putting his hand to ordinary labor with the servants’.11 When he died, a box of carpenter’s tools was found among his effects.

The connection between craftsmanship and godliness is well illustrated in the sermons of the Rev. John Cotton. Having served as the parish priest of Boston in Old England, he was appointed to the new post of teacher in the parish of Boston, Massachusetts, the pastorate of that church being already occupied. (Puritans preferred the term pastor to priest.) So authoritative were his observations on religious and related matters that he became known as the Un-mitred Pope of New England. Handiwork and holiness, observation and action are intimately tied together in his sermons: for example, ‘It is a disgrace to a good workman not to look at his work, but to slight it’ and ‘When a good workman seeth a man taken with his work, he is willing to show him all his Art in it’.12

With the coming of the machine tool in the first decades of the nineteenth century, this aptitude would translate itself into a fascination with the problems and opportunities of mass production. However, American men would retain in their bones at least some of the instincts of the craftsman. They loved to tinker, as Thomas Jefferson did in the eighteenth century; the third president of the United States wrote to a friend: ‘I am so much immersed in farming and nail making (for I have set up a nailery) that politicks are entirely banished from my mind’.13 David Freedman tells us of Tom Paine, author of The Rights of Man (1791), that ‘. . . long years as a staymaker left him with a skill that gave him great pleasure. Like his friend Franklin, he continued in many ways to be what he had been – a craftsman at heart.’14

Franklin had many credits to his name when he died. He had signed the Declaration of Independence on behalf of Pennsylvania. He had also invented bifocal lenses, the lightning rod and, to replace wasteful and dangerous open fires, the iron furnace stove that is still in use to this day. As a diplomat he had involved France in the war against the British, thereby turning the tide in favor of the colonists. Max Weber, sometimes described as the ‘founding father’ of sociology,15 regarded him as an exemplar of the Protestant Ethic – although the progenitor of some of its less attractive aspects. However, he retained to the end of his life a profound pride in his original trade – a pride first manifested in an epitaph penned for himself in his youth:

The body of

Benjamin Franklin, printer

like the cover of an old book,

its contents worn out.

and stripped of its lettering and gilding

lies here, food for worms!

yet the work itself shall not be lost,

for it will, as he believed, appear once more

in a new

and more beautiful edition

corrected and amended

by its author.

Regrettably, this epitaph would not be used on his tomb in Christ Church, Philadelphia.

One reason why American men became obsessed with their automobiles in the early twentieth century was precisely that they could tinker with them on Saturday morning. As late as the 1960s, if a company president did his own plumbing, he would ensure that this fact appeared in his official company biography; it showed he was a ‘real American’. A willingness to get their hands dirty distinguished managers from their European equivalents; this distinction reflected the relative lack of social stratification in the New World, the men at the top and bottom being considered to be made from the same common clay. Even today the ordinary house, being built of wood – unlike its European equivalent, which is of brick or stone – requires a large amount of maintenance and there is an assumption that the householder will do most of it himself or (increasingly) herself.

The third member of our quartet of traditional characteristics – the collective and co-operative nature of American Puritanism – is the one least remarked on. Many writers (like Weber) have perceived only a self-assertive and selfish individualism in the society that emerged from early colonial days but the truth is both more complex and more reassuring; while releasing the energies of the individual, the movement possessed a genius for bending them to a common purpose. In 1625, Bacon had set the tone in his essay, ‘On Friendship’, telling us that whoever ‘delighted in solitude is either a w...