![]()

CHAPTER 1

FRANCE

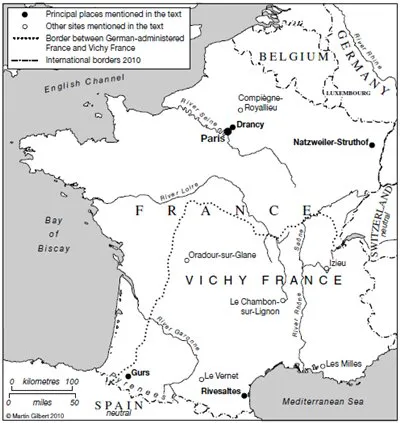

The history of the Holocaust in France is more controversial and paradoxical than in almost any other country. The wartime Vichy government was one of only two nominally autonomous regimes (the other being Slovakia) to voluntarily hand over Jews from its territory to the Nazis. Yet, despite far greater official collaboration than in most other countries, more than three quarters of French Jews survived.

There is evidence of a Jewish presence in what became France from as early as the first century and the kingdom became a major centre of Jewish life by the Middle Ages. However, rising anti-Semitism brought a recurring pattern of banishment and return until a final decree of expulsion in 1394. The only Jewish communities thereafter were those in territories annexed in the early modern period, primarily Alsace. It was the Revolution which changed their situation with the granting of full civil equality in 1791 – a first in Europe. This transformation created a highly integrated community characterised by assimilation, patriotism and, despite the poisonous Dreyfus Affair of the 1890s, a strong faith in the French state. However, this began to change from the 1880s. Whilst the number of indigenous Jews grew little, the overall population quadrupled between 1880 and 1939 due to immigration. The earliest arrivals were fleeing tsarist pogroms but, unusually, the great majority of immigrants entered the country after the First World War, including from the Third Reich. The Jewish population of around 330,000 in 1939 was thus stereotypically divided into respectable, secular, Francophone, middle-class ‘French’ Jews and radical, religious, Yiddish-speaking, poor ‘foreign’ Jews. The reality was inevitably rather more complex, not least because of a relaxation in the naturalisation laws in 1927. However, in the eyes of the state and many Jews themselves, there was a dichotomy between Jews in France which was to be of significance in the Holocaust.

As is well known, France quickly succumbed to the Germans in May 1940; the armistice of the following month divided the country into the occupied zone (the north and Atlantic coast) under direct German control and the ‘free’ zone (the south) governed by the Vichy regime of Marshal Pétain. It is less well known that Vichy still had sovereignty in the north, able to impose its policies as long as they did not conflict with those of the Germans, meaning that Pétain’s government had a key role in the Holocaust. This was reflected in the Statut des Juifs, anti-Jewish laws introduced in October 1940 without German prompting. German pressure was responsible for the creation of Vichy’s Office of Jewish Affairs in March 1941 to oversee anti-Semitic policy and of the Union of French Jews (UGIF) in November of the same year to coordinate and thus control all Jewish organisations. These developments reflected the growing importance of Eichmann’s representative Theodor Dannecker, as did round-ups in 1941 of several thousand foreign Jews who were sent to internment camps. Again, however, most of the camps were run by the French authorities. Some pre-dated the armistice, having been used to intern refugees from the Spanish Civil War and supposed ‘enemy aliens’ who, rather predictably, had been German and Austrian fugitives from Hitler, many of them Jews.

The escalation of Nazi policy in 1942 was assisted by the emergence of Pierre Laval as prime minister in April. Laval was reluctant to allow the deportation of French citizens but fully acquiesced in that of foreign-born Jews, even surprising the Nazis by pressing for the inclusion of children. Mass arrests began in the north in July, extending to the south in August (five months before Allied landings in Africa prompted the Germans and Italians to occupy the region). Most of those arrested passed through Drancy transit camp in the Parisian suburbs before being transported further east: more than 70,000 Jews were deported in more than 70 convoys up to 1944; only 2,566 survived. If we add those who were executed or who died in French camps, at least 77,021 people lost their lives, approximately 24 per cent of the Jews in France in 1939.

Another way of interpreting the figures, however, is to acknowledge that 76 per cent of French Jews survived, one of the highest proportions for any country. Why this should have been so has long intrigued historians. The answer is clearly not to be found in official Vichy policy although it did mean that widespread raids on French-born Jews did not begin until 1943. The Italian occupation of the south-east in November 1942 also provided a relatively safe haven until Italy’s surrender in September 1943. By this time, the war had clearly turned and there was thus greater reluctance on the part of French officials to comply whilst many Jews had been able to go into hiding. This latter development was facilitated by the geography of France but more importantly by the efforts of a committed minority of people. They included Jews themselves, through a variety of welfare organisations and rescue networks, along with specific groups of Gentiles, most famously the Protestant communities of the Auvergne and Languedoc. More generally, initial public indifference gave way to growing shame following the arrest of women and children in 1942, generating a greater willingness to help if only through what has been termed ‘benign neglect’ – officials ignoring suspect documents, townspeople not asking questions of newcomers, and the like.

Memorialisation before the 1990s tended to focus on sites exclusively associated with the Germans, reflecting a narrative in which the Jewish tragedy was seen as simply one part of a wider French tragedy. Public memorials have now been established which acknowledge the French state’s role whilst ambitious museums have recently opened or are currently under construction. These are amongst the most impressive in Europe, belated recognition of the horrors which befell French Jews – sometimes at French hands.

PARIS

With a Jewish population of approximately 200,000 in 1939, Paris was home to almost two-thirds of French Jews. It had been a major centre of Jewish life and learning in the medieval period until the fourteenth-century expulsions. Emancipation encouraged nineteenth-century settlement yet the population still numbered less than 50,000 in 1880. It was transformed by the waves of immigration thereafter: 110,000 Jews came to the city up to 1939, 90,000 of them from eastern Europe. The result was one of the continent’s most diverse Jewish communities.

The invasion prompted an exodus from the capital yet many Jews decided to return after the armistice, reassured by the stability that Pétain seemed to represent and by reports of the ‘correct’ behaviour of German troops. Even after anti-Semitic incidents in the summer of 1940, most complied when the Germans decreed a census of Jews in the occupied zone in October: according to the results, there were 149,734 Jews in the Paris region (around 10 per cent did not register). The results provided the basis for the first mass arrests, targeting male ‘foreign’ Jews, in May 1941: 3,747 were sent to internment camps. Further round-ups followed in August and December. After the Wannsee Conference, the December internees were sent to Auschwitz and plans were made for mass deportations. In the grande rafle of 16–17 July 1942, 12,000 foreign Jews were arrested, the largest such operation and one which profoundly affected opinion in the capital. By the end of August, virtually all had been murdered in Birkenau. Round-ups continued into 1943 and 1944 with French-born Jews increasingly likely to fall into the net. Even so, thousands of Jews continued to live in the city, many in hiding but others ‘legally’, saved by good fortune or the benevolence of bureaucrats. Estimates of the number of Jews in Paris at the time of the liberation in August 1944 range from 20,000 to 50,000.

Most survivors returned after the war. Although around a third of the 1940 population had been murdered, the community grew rapidly, due in part to immigration from France’s north African colonies. The result is that Paris today has an estimated Jewish population of 300,000, making it easily the largest community in Europe and one of the very few to have survived the Holocaust with its vitality and diversity intact.

The Marais and around

Jewish communities existed across the city by the end of the nineteenth century but the historic soul of Jewish Paris was the Marais in the third and fourth arrondissements, as it remains today despite gentrification. This was where most Parisian Jews lived at the time of the medieval expulsions. When large numbers returned in the early nineteenth century, they again took root in the Marais; as their children or grandchildren prospered and drifted to more affluent parts of the city, the area was resettled by the new waves of immigrants, giving it a character similar to London’s East End or New York’s Lower East Side. Even today, it is one of the few places in Europe where one will still hear Yiddish spoken. The heart of this community was and is the Pletzl (Yiddish for ‘square’), the group of streets around Rue des Rosiers (St-Paul Metro). The pre-war atmosphere is perhaps best preserved on Rue des Ecouffes, a street of tiny prayer houses, kosher butchers and Judaica shops running south from Rue des Rosiers. The Art Nouveau Agudath Hakehilot Synagogue at number 10 on parallel Rue Pavée was dynamited by the Nazis on Yom Kippur 1940 but restored after the war. Amidst the falafel stores, Hebrew bookshops and upmarket boutiques of Rue des Rosiers itself, there are hints of the district’s darkest hours in the regular plaques commemorating murdered inhabitants. The youngest victim recorded, Paulette Wajncwaig at number 16, was one month old. Plaques at nearby 8 Rue des Hospitalières-St-Gervais commemorate the 165 pupils of the Jewish boys’ school located at this address who were deported to their deaths and their headmaster Joseph Migneret who saved dozens of his charges before he too was killed.

South of the Pletzl is the Mémorial de la Shoah at 17 Rue Geoffroy l’Asnier, site of arguably the most impressive Holocaust museum in Europe (Sun–Fri, 10.00–6.00 (until 10.00, Thu); free; www.memorialdelashoah.org). The complex was originally created in the 1950s as the location of the Mémorial du Martyr Juif Inconnu, a now weather-beaten structure inscribed with the names of major camps and surrounded by bas-reliefs of Holocaust scenes by the Lithuanian-born artist Arbit Blatas. The redeveloped site, inaugurated in 2005, has clearly had a lot of thought and money put into it, evident from the moment one passes the open-air Wall of Names listing the names and years of birth of more than 70,000 murdered French Jews. The permanent exhibition covers the history of the Holocaust, displays on parallel walls tracing developments in France and in Europe as a whole. Video is used to good effect, and personal objects and biographies ensure that one never loses sight of individual tragedies. The exhibition exits into the heartbreaking Mémorial des Enfants, 2,500 photographs of murdered children. Other floors contain the crypt – a symbolic tomb containing ashes from the extermination camps – and excellent temporary exhibitions. Computer screens on the ground floor enable visitors to search lists of deportees whilst relatives can, by prior appointment, see victims’ police files, handed over to the memorial by former president Jacques Chirac. On the exterior wall of the complex, memorial plaques on Allée des Justes list the names of French citizens awarded the title Righteous Among the Nations.

Further south, hidden at the eastern tip of the Île de la Cité, is the Mémorial des Martyrs de la Déportation (daily, 10.00–12.00, 2.00–7.00), entered through a gate by Pont de l’Archevêché. Dedicated to all French citizens deported by the Germans, the 1962 monument contains the tomb of the Unknown Deportee, flanked by 200,000 fragments of lit glass and quotations from noted French writers. Though the memorial is undoubtedly of its time, it is a powerful, haunting place.

Paris’s Museum of Jewish Art and History is located north of the Pletzl in an elegant mansion at 71 Rue du Temple (Mon–Fri, 11.00–6.00; Sun, 10.00–6.00; €6.80; www.mahj.org), with a statue of Captain Dreyfus in the courtyard serving as a reminder of earlier persecution. The museum’s imaginative displays, mixing history, rituals and specific locations, effectively convey the plurality of the Jewish experience, augmented by a stunning array of objects. The wall of a small inner courtyard, visible from the stairs, lists the names of the inhabitants of this building who died – as in Berlin’s Große Hamburger Straße, this is the work of artist Christian Boltanski.

The Vélodrome d’Hiver

Outside Bir Hakeim Metro station, little noticed by the throng heading to the Eiffel Tower, Place des Martyrs Juifs du Vélodrome d’Hiver recalls one of the most tragic episodes of the Holocaust in France. The grande rafle of 16–17 July 1942 was not the first large-scale round-up but was the one which most deeply shocked Parisian opinion due to the preponderance of women and children amongst the victims. Beginning at 4 a.m. on Jeudi noir (16 July), 4,500 policemen combed the capital; by 5 p.m. the following day, they had arrested 12,884 people: 3,031 men, 5,802 women and 4,051 children. The final figure, tallied a few days later, was 13,152. This was actually far fewer than the number on the police lists as many Jews, hearing rumours of the imminent operation, had gone into hiding – although the police figures illustrate the widespread belief that only men would be victims, leaving women and children as the majority of those arrested. Almost 5,000 were taken directly to Drancy from where they were sent to Auschwitz in late July. Families with children under 16 were instead interned, in some cases for up to a week, in the Vélodrome d’Hiver, an indoor stadium which stood at the junction of Rue Nélaton and Rue du Docteur Finlay. More than 8,000 people were held in appalling conditions, the testimony of the few survivors emphasising the noise, lack of medical care, and, above all, appalling smell. From the ‘Vél d’Hiv’ they were subsequently transferred to transit camps in the Loiret. The Germans had originally intended to deport only adults but, in negotiations with Dannecker prior to the round-up, Laval (perhaps seeking to make up the numbers to preclude the arrest of French citizens) had suggested including children. This, however, required permission from Berlin which was received only in early August. The parents and older children were, therefore, deported to Auschwitz from late July whilst the fate of the youngsters was still being decided. This left around 3,500 effectively orphaned and largely unsupervised children in the camps in conditions which can only be imagined. Once approval was given, the terrified and bewildered children – some of the youngest could no longer even remember their names – were sent to Drancy. They were then dispatched in seven convoys to Auschwitz, with 500 children and 500 unrelated adults per train, a consequence of Berlin’s insistence that transports containing exclusively children should not be sent. Not a single child survived.

Paris: Vélodrome d’Hiver memorial (Photograph by the author)

The Vélodrome was later demolished but its unhappy history is remembered by two memorials. A small garden on Boulevard de Grenelle, south of the Metro line between Rue Nélaton and Rue Saint-Charles, contains a memorial plaque; south-west of Bir Hakeim, up steps between Quai de Grenelle and the Seine, an elevated park contains a beautiful figurative sculpture. The text at the base of the monument acknowledges the French state’s complicity.

Elsewhere

The former Levitan furniture store at 85–87 Rue du Faubourg Saint-Martin in the tenth arrondissement was turned into a sub-camp of Drancy in July 1943. ‘Privileged’ Jews – such as those married to Gentiles – were employed here sifting goods from looted apartments for shipment to Germany. A plaque recalls this history. In the nearby Gare de l’Est, there is a memorial plaque dedicated to Jewish deportees along with other plaques to French political prisoners, forced labourers sent to Germany and the 1945 returnees – the station was the main point of arrival for survivors, just as it had been in earlier generations for thousands of Jewish immigrants.

The Musée Nissim de Camondo at 63 Rue de Monceau in the eighth arrondissement (Wed–Sun, 10.00–5.30; €6; www.lesartsdecoratifs.fr; Monceau or Villiers Metro) is mainly visited for the magnificent collection of furniture and objets d’art accumulated by the Jewish aristocrat Count Moïse de Camondo. Its displays also illustrate how the Holocaust affected even the most integrated and prominent of French Jews: Camondo’s daughter Béatrice, her husband and their children were all murdered in Auschwitz.

Another Drancy sub-camp, performing the same function as Levitan, was established in the elegant corner mansion at 2 Rue de Bassano in the sixteenth arrondissement (Iéna or Alma-Marceau Metro), although there is no indication of its history at the site.

The Hotel Lutetia at 45 Boulevard Raspail (Sèvres Babylone Metro) in the sixth arrondissement, having previously been requisitioned by the Germans, was used to accommodate Jews and political prisoners returning from Germany in 1945. This was where families of deportees came to enquire about the fate of their loved ones. By the entrance a large bulletin board was placed which desperate relatives covered in notices, pre-war photographs and long lists of missing persons; their searches were invariably in vain.

DRANCY

The most significant location associated with the Holocaust in France, Drancy had unlikely beginnings as a large-scale housing project in the northern suburbs of Paris. Constructed between 1932 and 1936 as a model of modernist architectural principles, it only briefly served as municipal housing before conversion into police barracks. An internment camp for foreign Jews was established on the site in August 1941 although its 4,500 capacity was soon stretched. Once deportations commenced in 1942, Drancy became the principal transit camp for the whole of France: Jews held in other camps or arrested in the provinces invari...